Saturday Links

John Singer Sargent's "tender specificity," baseball books, short sentences, the liturgy of medieval parish churches, Barbara Pym at MI5, and more.

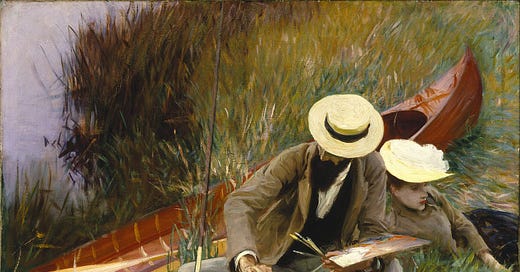

Good morning! Lisa Yin Zhang writes about the “tender specificity of John Singer Sargent” in Hyperallergic:

John Singer Sargent was just 18 when he arrived in Paris in 1874. In the ensuing decade, he would not only launch his career as a painter, exhibiting and earning accolades at multiple salons, but also embark on travels that would permanently inflect his practice and establish the connections that would fund his work, including upper-crust socialites, athletes, and financiers; writers like Henry James; and artists like Monet, Renoir, and Rodin. Portraits of and by many of those very figures are on view in Sargent and Paris at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Indeed, what comes through most strongly in this exhibition is his humanistic bent: Sargent loved people, and it shows.

All great art is humane in the sense that it depicts—with specificity and nuance—what it feels like to be human, even if the artist is a bit of a misanthrope. All that to say, maybe Singer Sargent “loved people” or maybe he didn’t, but it doesn’t matter. What matters is the work.

Tom Shippey reviews the third and final book of Max Adams’s The Mercian Chronicles:

The word ‘Mercia’ is a Latinisation of the Anglo-Saxon name. In West Saxon, the kingdom was called the Mearc, that is ‘the Mark’, while its inhabitants were the Mierce (pronounced ‘Meercher’), ‘the people of the March’ or ‘the Borderers’. Mercia was, however, surrounded by borders: Northumbria to the north, Wessex to the south, East Anglia to the east, and to the west, the post-Roman kingdoms of the Welsh. Probably it was the last that led to Mercians being called ‘Marchers’. For a while that was the open frontier of Anglo-Saxon expansion, until the line was eventually drawn by Offa’s Dyke, Mercia’s answer to Hadrian’s Wall, built sometime in the late eighth century.

Mercia matters because it was the English heartland, covering almost half of the 39 historic English counties. The rest were shared unevenly between Wessex, Northumbria and East Anglia, which also between them absorbed the smaller polities of Kent, Sussex, Essex and Middlesex. Mercia was, Adams claims, ‘the crucible of the English state’. The West Saxons may have promoted their version of the national story more successfully, but it is salutary to remember that if things had gone differently, the capital of England might be Tamworth (which has a population today of about eighty thousand), with its senior archbishopric in Lichfield a few miles away. Adams’s account also points us to the importance of such unfamiliar places as Wall and Hanbury (both Staffordshire) and even Claybrooke Parva (Leicestershire). It’s a new geographical perspective, as well as a historical one.

What would it have been like to worship in medieval parish churches? Bijan Omrani reviews Cosima Clara Gillhammer’s Light on Darkness: The Untold Story of the Liturgy: “Instead of dissecting the subject into chronological periods, Gillhammer offers a number of chapters based on a round of universal human experiences, for example ‘Love’, ‘Hope’, ‘Suffering’, ‘Grief’, ‘Death’, ‘Time’, showing how they find their place in the liturgy, and then how treatments of these experiences in art, music, literature and culture more widely have been influenced by the liturgy from the Middle Ages even to the present day.”

Did the novelist Barbara Pym work for MI5? Claire Smith believes she did: “It is an irony that she herself would have revelled in: Barbara Pym, the author who punctured the social strictures of 20th-century Britain, worked as a censor during the second world war. But research suggests that rather than just poring over the private letters that must have helped hone her talent, she may have also been working for MI5.”

Jospeh Epstein reviews John McWhorter’s new book, Pronoun Trouble: The Story of Us in Seven Little Words:

This new interest in pronouns has provided a field day for linguists. The job of the linguist, as John McWhorter, perhaps the best-known linguist of our day, has described it in his book Nine Nasty Words, is to find “structure in what seems like chaos, mess, or the trivial … we take in what looks like a mess and try to make out the sense in it. We like to think of ourselves as scientists. … The idea is to find the sense in the chaos.”

A better guide through this maze than John McWhorter is not readily imagined. He brings to the task a strong element of good sense, nicely combined with references to contemporary movies, television, and popular culture at large. He adds touches of levity throughout.

Bari Weiss talks to him about the book here, and he and Malcolm Gladwell have a conversation about it at the 92nd Street Y, which you can watch here.

Benjamin Kunkel reviews a new translation of Karl Marx’s Capital for Harper’s: “The task of reading Capital naïvely acquires a fresh jolt of plausibility in the case of Paul Reitter’s new translation of volume one. Until now, the standard in this language has been the Englishman Ben Fowkes’s elegant 1976 version. Based on an edition brought out by Marx’s friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels seven years after Marx’s death, Fowkes’s volume one incorporates material Marx had drafted but not included in either German-language edition published during his lifetime. Reitter, an American, has chosen instead to work from the second German edition, of 1872, the last version that Marx himself approved. Another feature of Reitter’s version is to stick closer to the ungainly neologisms of Marx’s German, so that, for example, Fowkes’s not-too-weird phrase “the objectivity of commodities as values” becomes—or remains—the weirder “value-objecthood”: no doubt a mystifying term for anyone who hasn’t yet got the hang of Marx’s argument, just as his Werthgegenständlichkeit would have been for the first readers of Das Kapital. The result is that just these English words, representing just this original document, make for a new and somewhat undiscovered book, even to Marxist adepts.”

The Observer goes it alone: “Observer editor-in-chief and major shareholder James Harding set out his stall in the first issue under its new Tortoise ownership on Sunday. He said the paper was leaning into traditions of liberalism and editorial independence which date back to its foundation in 1791.”

Poem: Kelly Scott Franklin, “Acquired Taste”

A new press will focus on publishing male writers: “Conduit Books, founded by Jude Cook, will publish literary fiction and memoir, ‘focusing initially on male authors’. Cook said the publishing landscape has changed ‘dramatically’ over the past 15 years as a reaction to the ‘prevailing toxic male-dominated literary scene of the 80s, 90s and noughties’. Now, ‘excitement and energy around new and adventurous fiction is around female authors – and this is only right as a timely corrective’.”

I disagree. The corrective we need is for publishers to ignore sex and race and simply publish the best writing they can. This doesn’t mean that presses should never ask themselves about blind spots, but that is different from implementing inflexible institutional policies.

The tyranny of agitslop: “Agitslop is easily defined — it is art made by social workers, not artists; content produced neither to inform, educate or entertain the viewer, but to gently marinade them in moral instruction. Sentimentality and didactic messaging are its hallmarks, along with high production values that allow it to reasonably pass for entertainment.”

People are writing shorter sentences. Why? “The average sentence length was 49 for Chaucer (died 1400), 50 for Spenser (died 1599), 42 for Austen (died 1817), 20 for Dickens (died 1870), 21 for Emerson (died 1882), 14 for D.H. Lawrence (died 1930), and 18 for Steinbeck (died 1968). J.K Rowling averaged 12 words per sentence (wps) writing the Harry Potter books 25 years ago. So the decline predates television, the radio, and the telegraph—it’s been going on for centuries. The average sentence length in newspapers fell from 35wps to 20wps between 1700 and 2000. The presidential State of the Union address has gone from 40wps down to under 20wps, and the inaugural addresses had a similar decline . . . Warren Buffett’s annual letter to shareholders dropped from 17.4wps to 13.4wps between 1974 and 2013.”

John Wilson writes about baseball books: “Several weeks ago, in sync with the start of Major League Baseball’s 2025 season, the University of Nebraska Press published David Krell’s 1978: Baseball and America in the Disco Era. It is the third such volume Krell has done, following 1962: Baseball and America in the Time of JFK (2021) and Do You Believe in Magic? Baseball and America in the Groundbreaking Year of 1966 (2022). If you are a heavy reader of baseball books, especially one old enough to actually remember the years 1962, 1966, and 1978, on and off the diamond, you should check Krell’s books out. They are workmanlike, while at the same time conveying a longstanding passion for baseball. And the notion of zeroing in on a particular year in this way has an inherent appeal (for this reader, at least), even if the choices of what to focus on in the culture at large tend to be scattershot, only intermittently productive of insight.”

McNally Jackson is starting a book festival: “Beginning this spring, New York–based bookstore McNally Jackson is holding a twice-yearly festival that will take place mostly at its Seaport location. The first festival, a slate of events organized around the idea of archives, historiography, and legacies, is a sprawling affair: It will run from May 7 into June, with a series of talks, a print zine, and a phone-free closing party (involving ‘a secret lineup’ and a musical guest) at newly hip Irish pub T.J. Byrnes in the Financial District. The second program, set to happen later this year, will be about New York City history and civic life.”

"Light on Darkness". Sounds like a good one. Ordering now! Thanks, Micah!

So many good gems in this one! Baseball, linguistics, and liturgy / rituals are some of my favorites things to read about so this was right up my alley