Winter Books

Also: A history of Harper's "Easy Chair" column, eating icons, Daniel Defoe's triumph of travel writing, and more.

Happy New Year! I hope everyone had a refreshing holiday season. My wife and I had a wonderful time in Victoria, but we are also glad to be back home and back to our weekly routines.

Part of that weekly routine for me is this email, and I thought I’d start the year off with a quick look at forthcoming winter books that have piqued my interest.

The book I am most looking forward to is Adam Plunkett’s new biography of Robert Frost (FSG, February 18), which promise to bury Lawrance Thompson’s vindictive biography of the poet. Here’s a snippet from the jacket:

By the middle of the twentieth century, Robert Frost was the best-loved poet in America. He was our nation’s bard, simple and sincere, accompanying us on wooded roads and articulating our hopes and fears. After Frost’s death, these cliches gave way to equally broad (though opposed) portraits sketched by his biographers, chief among them Lawrance Thompson. When the critic Helen Vendler reviewed Thompson’s biography, she asked whether anyone could avoid the conclusion that Frost was a “monster.”

In Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry, Adam Plunkett blends biography and criticism to find the truth of Frost’s life―one that lies between the two poles of perception. Plunkett reveals a new Frost through a careful look at the poems and people he knew best, showing how the stories of his most important relationships, heretofore partly told, mirror dominant themes of Frost’s enduring poetry: withholding and disclosure, privacy and intimacy. Not least of these relationships is the fraught, intense friendship between Frost and Thompson, the major biographer whose record of Frost Plunkett seeks to set straight.

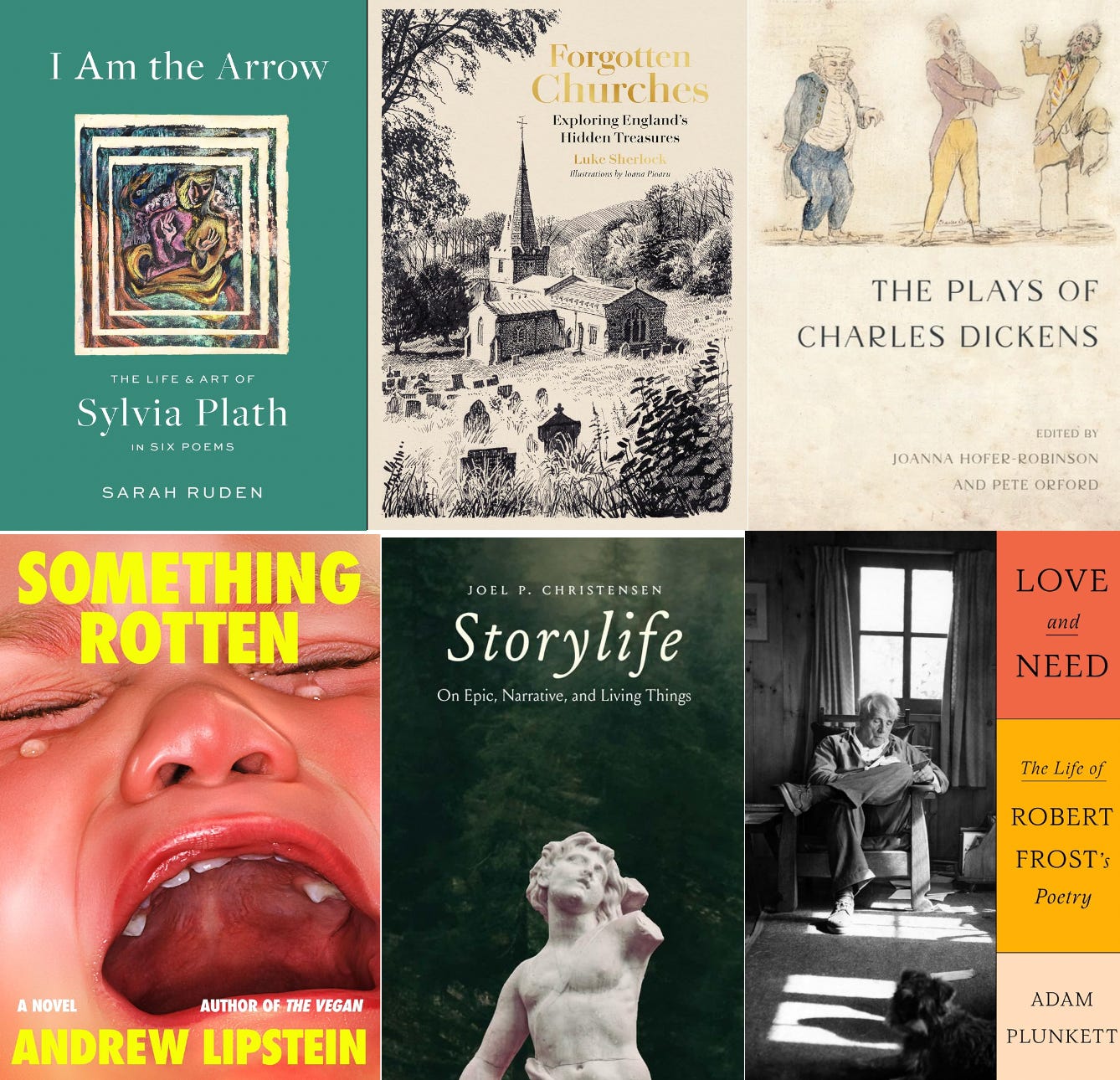

The beginning of the year is actually looking pretty good as far as works of biographical criticism are concerned. In addition to Plunkett’s Frost bio, we have Sarah Ruden’s biography of Sylvia Plath (LOA, March 25). According to the jacket, Ruden “shares a fresh, myth-busting reading of Sylvia Plath’s poems, revealing the full range and towering ambition of a great American poet.”

Janet Todd gives us an apparently “intimate” portrait of Jane Austen’s life and work in Living with Jane Austen (Cambridge, March 20): “Written to coincide with Austen's 250th birthday, this approachable and intimate work shows why and how - for over half a century - Austen has inspired and challenged its author through different phases of her life. Part personal memoir, part expert interaction with all the letters, manuscripts and published novels, Janet Todd’s book reveals what living with Jane Austen has meant to her and what it might also mean to others.”

Richard Kopley attempts to give us “the most comprehensive critical biography of Poe yet produced” in Edgar Allan Poe: A Life (Virginia, March 18). It is nearly 800 pages long. That’s 20 pages for every year of Poe’s life.

Sally Wolff takes a closer look at William Faulkner’s relationship to the town of Holly Springs in William Faulkner in Holly Springs (Mississippi, March 17).

Tess Chakkalakal’s A Matter of Complexion: The Life and Fictions of Charles W. Chesnutt (St. Martin’s, February 4) is being pitched as the first biography of the African-American novelist. Let’s just hope it avoids identitarian claptrap: “Through his literary work, as a writer, critic, and speaker, Chesnutt transformed the publishing world by crossing racial barriers that divided black writers from white and seamlessly including both Black and white characters in his writing. In A Matter of Complexion Chakkalakal pens the biography of a poor teacher raised in rural North Carolina during Reconstruction who became the first professional African American writer to break into the all-white literary establishment and win admirers as diverse as William Dean Howells, Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells, and Lorraine Hansberry.”

There are some other great biographies slated for the first of this year, as well. Stephen J. Campbell’s biography of Leonardo da Vinci (Princeton, February 4) “examines the strangeness of Leonardo’s words and works and the distinctive premodern world of artisans and thinkers from which he emerged.”

Nicola Moorby gives us a double life of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable (Yale, March 11), who were born just 14 months apart: “The two men have routinely been seen as polar opposites, not least by their peers. Differing in temperament, background, beliefs and vision, they created images as dissimilar as their personalities. Yet in many ways they were fellow travellers. As children of the late 18th century, both faced the same challenges and opportunities. Above all, they shared common cause as champions of a distinctively British art. Through their work, they fought for the recognition and appreciation of landscape painting – and in doing so ensured their reputations were forever intertwined and interlinked.”

David T. Byrne has written an “intellectual biography” of James Burnham (Northern Illinois, March 15). Here’s the jacket copy:

Beginning his intellectual career as a disciple of Leon Trotsky, Burnham preached socialist revolution to the American working classes during the Great Depression. In 1940 he split with Trotsky over the nature of the USSR. Attempting to explain the world that was emerging in the early days of World War II, Burnham penned one of the most successful political works of the early 1940s, titled The Managerial Revolution. This dystopian treatise predicted collectivization and rule by bland managers and bureaucrats. Burnham's next book, The Machiavellians, argued that political elites seek only to obtain and maintain power, and democracy is best achieved by resisting them.

After World War II, Burnham became one of the foremost anticommunists in the United States. His The Struggle for the World and The Coming Defeat of Communism remain two of the most important books of the early Cold War era. Rejecting George F. Kennan's policy of containment, Burnham demanded an aggressive foreign policy against the Soviet Union. Along with William F. Buckley, Burnham helped found National Review magazine in 1955, where he expressed his political views for more than two decades. As Byrne shows in James Burnham, the political theorist's influence has stretched from George Orwell to Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump's base. Burnham's ideas about the elite and power remain part of US political discourse and, perhaps, have more relevance than ever before.

I don’t know if Yvonnick Denoël’s Vatican Spies: From the Second World War to Pope Francis (Hurst, February 3) has an anti-Catholic bias or not, but it sounds interesting: “Drawing on freshly released archives of foreign services that worked with or against the Holy See, Vatican Spies reveals eighty years of shadow wars and dirty tricks. These include infiltrating Russian-speaking priests into the Soviet Union; secret negotiations between John XXIII and Khrushchev; the future Paul VI’s close relationship with the CIA; the Vatican's infiltration by Eastern Bloc intelligence; the battles between the Jesuits and Opus Dei; and the secret bank funds channeled first to fight communism in South America, then to support Solidarity in Poland. This entertaining book journeys right to the present, uncovering startling machinations under Benedict XVI and, today, Pope Francis.”

Carol Atack focuses on Plato’s relationship to Athens in Plato: A Civic Life (Reaktion, January 10): “Plato is a key figure from the beginnings of Western philosophy, yet the impact of his lived experience on his thought has rarely been explored. Born during a war that would lead to Athens’ decline, Plato lived in turbulent times. Carol Atack explores how Plato’s life in Athens influenced his thought, how he developed the Socratic dialogue into a powerful philosophical tool, and how he used the institutions of Athenian society to create a compelling imaginative world.”

Matthew Pearl writes about a real Swiss Family Robinson in Save Our Souls: The True Story of a Castaway Family, Treachery, and Murder (Harper, January 14): “On December 10, 1887, a shark fishing boat disappeared. On board the doomed vessel were the Walkers—the ship’s captain Frederick, his wife Elizabeth, their three teenage sons, and their dog—along with the ship’s crew. The family had spotted a promising fishing location when a terrible storm arose, splitting their vessel in two and leaving those onboard adrift on the perilous sea. When the castaways awoke the next morning, they discovered they had been washed ashore—on an island inhabited by a large but ragged and emaciated man who introduced himself as Hans. Hans appeared to have been there for a while and could quickly educate the Walkers and their crew on the island’s resources. But Hans had a secret . . . and as the Walker family gradually came to learn more, what seemed like a stroke of luck to have the mysterious man’s assistance became something ominous, something darker.”

Ian Wardropper writes about the Frick family in The Fricks Collect: An American Family and the Evolution of Taste during the Gilded Age (Rizzoli Electa, March 11): “At its heart, this story centers on Frick and his daughter Helen Clay Frick, both pivotal figures in the formation of the renowned Frick Collection. The volume delves into the Fricks’ exposure to and acquisition of some of the finest art of their time. With an exquisite blend of textual narrative and ample imagery showcasing masterpieces and the sumptuous interiors of homes in Pittsburgh and New York, the book offers a captivating narrative of ambition, wealth, and cultural patronage.”

Last year I read two Joan Didion biographies. Both authors—heaven knows why—tried to write like Didion as they wrote about her and made something of a fool of themselves. I am sure Alissa Wilkinson will avoid this error in We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine (Liveright, March 11): “We Tell Ourselves Stories eloquently traces Didion’s journey from New York to her arrival in Hollywood as a screenwriter at the twilight of the old studio system. She spent much of her adult life deeply embroiled in the glitz and glamor of the Los Angeles elite, where she acutely observed―and denounced―how the nation’s fears and dreams were sensationalized on screen. Meanwhile, she paid the bills writing movie scripts like A Star Is Born, while her books propelled her to celestial heights of fame. Peering through a scrim of celluloid, Wilkinson incisively dissects the cinematic motifs and machinations that informed Didion’s writing―and how her writing, ultimately, demonstrated Hollywood’s addictive grasp on the American imagination.”

A couple of works of history also caught my eye. Luke Sherlock’s survey of English churches (Frances Lincoln, March 18) sounds interesting and looks beautiful: “Travelling to all corners of England – from the Kent marshlands to the Norfolk fens, Yorkshire hills, Somerset lanes and beyond – Sherlock carefully documents these unique buildings, celebrating their histories and decoding their hidden meanings. Bringing together 70 of the most unusual, intriguing and atmospheric of England’s churches, Sherlock tells stories of craftsmanship and local community, whilst centering these buildings at the heart of our national story and revealing their forgotten secrets and cultural significance.”

I am a bit of a sucker for medieval history and histories of books, so I am looking forward to Anne Lawrence-Mathers’s The Magic Books: A History of Enchantment in 20 Medieval Manuscripts (Yale, March 11), which “explores the medieval fascination with magic through twenty extraordinary illuminated manuscripts.”

Ada Palmer’s Inventing the Renaissance: The Myth of a Golden Age (Chicago, March 10) is being pitched as an “irreverent new take on the Renaissance”:

From the darkness of a plagued and war-torn Middle Ages, the Renaissance (we’re told) heralds the dawning of a new world—a halcyon age of art, prosperity, and rebirth. Hogwash! or so says award-winning novelist and historian Ada Palmer. In Inventing the Renaissance, Palmer turns her witty and irreverent eye on the fantasies we’ve told ourselves about Europe’s not-so-golden age, myths she sets right with sharp clarity.

Palmer’s Renaissance is altogether desperate. Troubled by centuries of conflict, she argues, Europe looked to a long-lost Roman Empire (even its education practices) to save them from unending war. Later historians met their own political challenges with a similarly nostalgic vision, only now they looked to the Renaissance and told a partial story. To right this wrong, Palmer offers fifteen provocative portraits of Renaissance men and women (some famous, some obscure) whose lives reveal a far more diverse, fragile, and wild Renaissance than its glowing reputation suggests.

On the literary front, Ecco is bringing out a new collection of Czeslaw Milosz’s early poems (February 4), which are appearing for the first time in translation: “Equal parts affecting and illuminating, Poet in the New World is an essential addition to the Milosz canon, in a beautifully rendered translation by Robert Hass and David Frick, that reverberates with the questions of histories past, present, and future.”

The University of Edinburgh will publish a new collection of Charles Dickens’s plays (March 31)—“the first complete scholarly edition of Dickens’s dramatic works.” It is edited by Joanna Hofer-Robinson and Pete Orford.

Brad Leithauser will publish a new collection of poems (Knopf, March 4). So will Ange Mlinko (FSG, January 28). C. Dale Young has a new and selected poems coming out with Four Way Books (March 15). Shane McCrae’s New and Collected Hell: A Poem will be published by FSG in February.

Cynthia Ozick’s In a Yellow Wood: Selected Stories and Essays will be published by Everyman’s in March. It’s a whopping 712 pages long. Andrew Lipstein is a novelist I find intriguing. His latest novel, Something Rotten (FSG), will be published later this month. Colum McCann’s Twist (Random House) is slated to be published on March 25th. Random House will also published a selection of W.G. Sebald’s essays on writers who influenced the late writer that have never been translated into English.

I’m looking forward to reading Ross Douthat’s Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious (Zondervan, February 11), Nicholas Carr’s Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart (Norton, January 28), Chris Hayes’s The Sirens’ Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource (Penguin, January 28), and Joel P. Christensen’s Storylife: On Epic, Narrative, and Living Things (Yale, January 14).

In other news, Malcolm Forbes revisits Daniel Defoe’s A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain: “Today the book isn’t as well-read as it should be, but it remains a triumph of travel writing.”

John Wilson writes about his favorite books of 2024. His book of the year is Kevin Hart’s memoir Dark-Land.

In the London Review of Books, Alexander Bevilacqua reviews Iconophages: A History of Ingesting Images: “Some time in the sixth or early seventh century, a woman in Constantinople was suffering from severe abdominal pain. One night she crawled out of bed and dragged herself to the part of the house where frescoes of the Christian martyrs Cosmas and Damian had been painted on the wall. ‘Leaning on her faith as upon a stick’, she dug her fingernails into the plaster, then dissolved the scrapings in water and drank the resulting brew. Her pain abated immediately. As Jérémie Koering puts it in his new book, ‘the woman was healed by eating an image.’”

In National Review, Andrew Ferguson writes about William F. Buckley’s style—prose and otherwise:

The letter writer, signing himself (surely not herself) merely as “Fellow Conservative,” had a grievance with William F. Buckley. The year was 1977, nearly 50 years ago, long before conservatives began making grievance their daily meat.

“You are one of the leading conservatives in this country,” this Fellow began his letter, “but you wear your hair like a way-out liberal hippy.” The incongruity between Buckley’s lapidary political views and his untidy appearance was simply too much for the letter writer to square. “If you really are conservative,” Fellow concluded, “why don’t you make yourself look like one?”

Buckley replied with a wryly ironic humble-brag — “If I were also good looking, don’t you think it would be just too much?” — and the letter was duly reprinted in NR’s “Notes and Asides” department.

Also in National Review (the latest issue commemorates William Buckley at 100), Bill Mehann writes about Buckley’s Blackford Oakes Mysteries:

When, in 1996, I interviewed William F. Buckley Jr. about his Cold War fiction, I waited an hour to bring up a subject that made me a bit uneasy. The public, after all, had come to know Buckley as a conservative Catholic who was critical of the Second Vatican Council and had written three dozen articles about two popes. I simply could not, however, leave his office at National Review, on East 35th Street, without asking about an aspect of his spy novels that might seem to be at odds with his beliefs: the philandering ways of protagonist Blackford Oakes.

“Well, in my judgment,” Buckley answered, “when you write a novel post– about 1955, there’s got to be a sexual element. I remember one time having dinner with Nabokov in Switzerland, which was a yearly event. I said, ‘You look very pleased with yourself today, Vadim.’ He said, ‘I am, I have finished my OSS.’ ‘What’s OSS?’ ‘Obligatory sex scene.’”

Buckley explained to me that the sexual factor was so widespread in popular culture that it had become “a conventional daily element in the imaginary life.” So, he concluded, “a book that doesn’t have it is a book about which people, not even knowing what it is, tend to feel something’s missing. I recognized this even starting in, and have those two scenes in Saving the Queen, one involving the brothel and the other the queen herself.”

Why are teachers quitting? Stephen G. Adubato explains in Compact:

In October 2023, 86 percent of schools belonging to the National Education Association indicated that they were seeing more educators leave the profession since the start of the pandemic. Numerous school districts—especially in lower-income neighborhoods—are faced with teacher shortages. Many of these former teachers, like DeSimone, are heartbroken—even bitter—about what they once thought of as their dream jobs. Some have taken to YouTube and social media to tell their “Why I Quit Teaching” stories.

The stories conveyed in this viral trend match the data. Those who leave teaching behind cite low pay (since 1996, the average wage of a public school teacher has risen just $29, $416 less than the average wage increase earned by other college graduates), unmanageable class sizes, lack of support from both administrators and parents, and disrespect from students.

In Harper’s, Christopher Carroll writes about the history of the magazine’s “Easy Chair” column: “William Dean Howells called it his ‘Uneasy Chair.’ Lewis H. Lapham thought it ‘a column always grotesquely misnamed.’ Bernard DeVoto simply wanted to do something else—a books section—and tried to fob the job off on H. L. Mencken, who wasn’t available. For the better part of two centuries, the Easy Chair—the oldest column in American journalism—has as often as not been a source of grief for its occupants.”

Thx. What fun. Glad you’re back at routine!

Wonderful list! One more to watch out for: https://undpress.nd.edu/9780268209186/the-invisibility-of-religion-in-contemporary-art/