Winter Books

Also: A history of stained glass, the thought of Paul Elmer More, the point of the Hundred Years War, the Bronze Age Pervert’s doctoral dissertation, and more.

Every few months, I post a list of forthcoming books that pique my interest. I don’t expect to love every title. I was looking forward to read Evelyn McDonnell’s Joan Didion book a few months ago, and it turned out to be terrible. But I do hope that most titles are worth it. So with that by way of introduction, here are a few winter books I am keeping an eye on.

Nicholas Shakespeare’s Ian Fleming: The Complete Man was widely praised in Britain. The American edition of the biography is slated for March 12 and will be published by Harper.

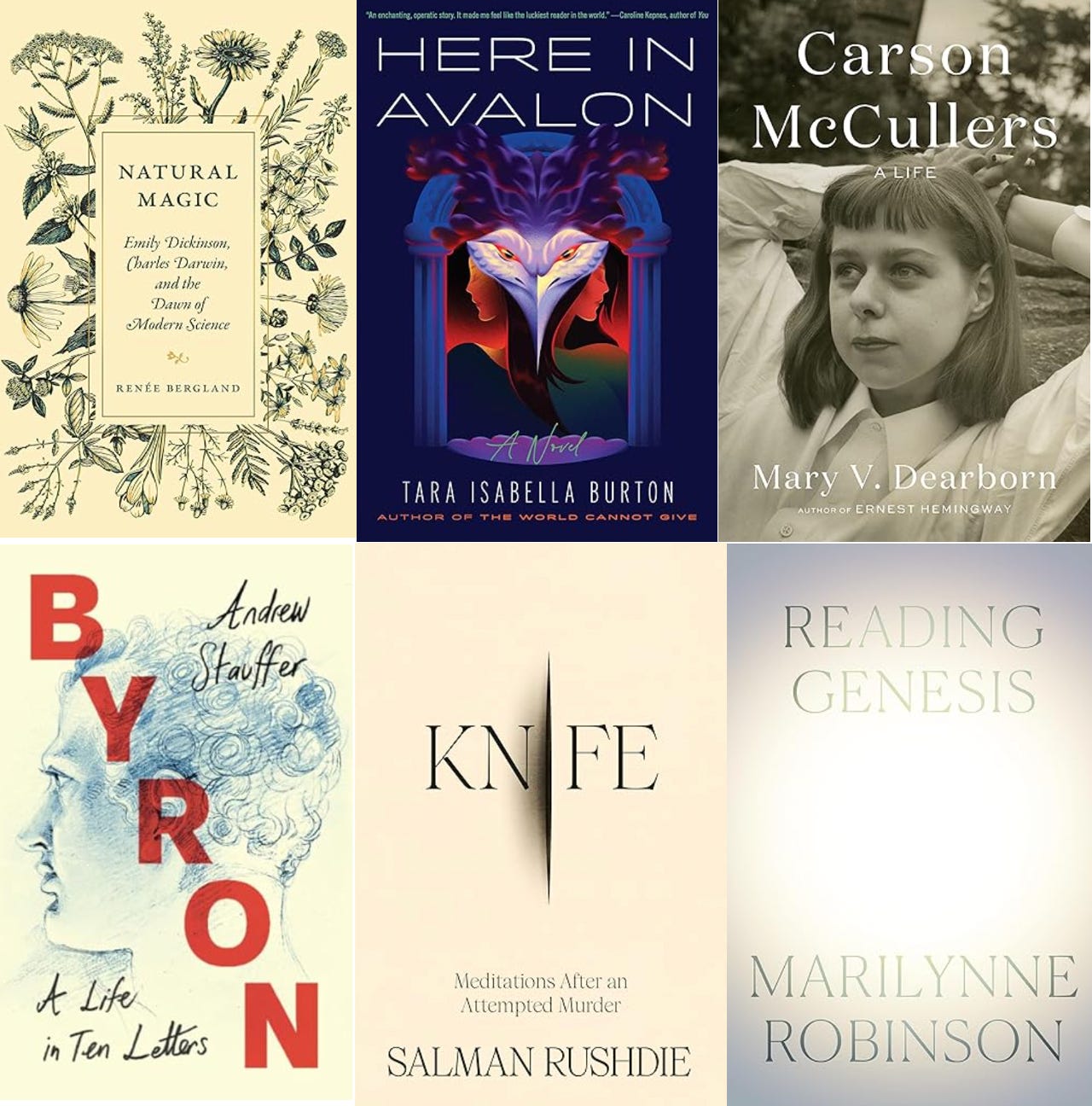

I don’t read as much fiction as John Wilson does, but I am looking forward to Tara Isabella Burton’s Here in Avalon (Simon & Schuster, January 2) and Francis Spufford’s Cahokia Jazz: A Novel (Scribner, February 6). The jacket copy for Burton’s novel speaks for itself: “An ‘enchanting’ New York City fairy tale about two sisters that fall under the spell of an underworld cabaret troupe that might be a dangerous cult—but one that makes the materialist world left in its wake feel like a sinister cult itself.” Spufford’s novel sounds intriguing. It is set in the 1920s and “reimagines how American history would be different if, instead of being decimated, indigenous populations had thrived.” Spufford is a gifted writer. The question is will he give us a complex work of human drama or political claptrap. I’m betting on the former.

I love Marilynne Robinson’s novels, but her nonfiction is a mixed bag. Some essays (or collections of essays) are excellent. Others are not. What leads her astray is when she treats her progressive ideas as fact. I am hoping she will avoid this in Reading Genesis (FSG, March 12), which is being billed as an “appreciation” of Genesis’s “greatness as literature.”

A little off the beaten path: Mark Ramseyer and Jason M. Morgan show in The Comfort Women Hoax that the idea that Japanese prostitutes during the Second World War were “dragooned into sex slavery at bayonet point by Japanese infantry” was a hoax perpetrated by a Japanese communist writer in the 1980s. The book, in turn, is about how Western academics accepted the hoax blindly and have shouted down anyone—Ramseyer and Morgan in particular—who dissent.

Mary V. Dearborn’s biography of Southern writer Carson McCullers will be published in February by Knopf. It is being pitched as “based on newly available letters and journals.”

Next year marks the 200th anniversary of Byron’s death in Greece. Reading Andrew Stauffer’s Byron: A Life in Ten Letters (Cambridge, February 22) seems like a suitable way to mark the occasion.

Peter Vertacnik’s collection of prize-winning poems, The Nature of Things Fragile, will be published at the end of January. It is sure to dazzle.

Denise Levertov’s Collected Poems will also be published at the end of January by New Directions.

A little further out, I am looking forward to The Collected Poems of Delmore Schwartz (FSG, April 2), edited by Ben Mazer; Julia Alvarez’s The Cemetery of Untold Stories: A Novel (Algonquin, April 2); Joseph Epstein’s Never Say You've Had a Lucky Life: Especially If You've Had a Lucky Life (Free Press, April 16); Salman Rushdie’s Knife: Meditations after an Attempted Murder (Random House, April 16); and Ward Farnsworth’s Classical English Argument. I reviewed Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric and Classical English Metaphor for The Weekly Standard back in the day and still use both books on occasion in the classroom.

Finally, I hope someone pairs these two books in a review: The “definitive” edition of Emily Dickinson’s letters (Belknap, April 2) and Renée Bergland’s Natural Magic: Emily Dickinson, Charles Darwin, and the Dawn of Modern Science (Princeton, April 30).

In other news, Tom Shippey reviews Jonathan Sumption’s fifth volume of his history of the Hundred Years War: “There can be no doubt about the scale of Jonathan Sumption’s achievement in his history of the Hundred Years War. Five massive volumes, published between 1990 and this year, each more than six hundred pages of narrative and notes. Together, they total nearly four thousand pages, not counting the bibliographies, with their ever expanding lists of secondary contributions as well as primary sources in Latin, French, Middle English, Dutch, Catalan and Portuguese. And all this done in Sumption’s spare time from his work as a barrister and then a justice of the UK Supreme Court. But what is the result? Was the Hundred Years War special in anything except its duration?”

Bardia Sinaee, who just finished editing the most recent Best Canadian Poetry, complains in the Literary Review of Canada that “Canadian poets and magazine editors have confused good poetry with good politics”: “Many poems in journals today consist primarily of solipsistic observations, social justice tropes, and moralizing narratives delivered in a uniform first-person voice. They are wooden and boring. What’s worse, poets cheapen political subject matter when they treat it with formal laziness or as a platform to signal their virtue. I don’t believe poetry has gotten worse. Great poems continue to be written and published, as I hope the anthology demonstrates. However, the editorial curation now skews heavily in favour of poetry with a social justice message, regardless of how (or how well) it’s written. This orthodoxy is stifling. I read hundreds of magazines in the course of a year, and sometimes it seemed like every other poem was about trauma or the politics of personal identity. Some of these were excellent, but many were indistinguishable fluff.”

Dan Hitchens writes about the history of stained glass in Spectator:

Stained glass likes an epic theme. At Chartres the north window displays twenty-four Old Testament kings and prophets; the upper chapel of Sainte-Chapelle tells the story of the Bible from the Creation to the life of Christ. The Illuminated Window, a new, exhaustively detailed and comprehensively illustrated book by Virginia Chieffo Raguin, guides the reader through these grand projects. Though of course, with stained-glass windows you don’t need to follow the story. It can be a narrative art, but it also works in the way that a Jackson Pollock does — an explosion of color which, when the eye simply rests on it, evokes an immense peace.

If stained glass is supremely a medieval art, that is perhaps unsurprising, since the Middle Ages loved to speculate on the nature of light. Some believed it was the fundamental element of the universe. It was also a useful way of thinking about how Jesus Christ related to God the Father: “light from light,” as the Apostle’s Creed expressed it. Naturally, then, the modern revival took inspiration from the medieval master-craftsmen.

Typical in this regard was Louis Comfort Tiffany, who in 1865 visited the V&A’s collection and was spellbound by the medieval glass, its deeper colors and varied textures. Back in New York he started his own factory, thus initiating what became American Art Nouveau.

James Kalb looks back at the life and thought of Paul Elmer More in Chronicles: “His view of the world changed repeatedly and drastically during his life. Each step, however, was a natural progression from the preceding one. Thus, he reacted against his early unbridled romanticism by becoming a strict materialist. He then accepted successively the reality of spirit, the coordinate reality of the material world, a Platonic appreciation of the Good, Beautiful, and True as principles that relate the two. Finally, after the age of 60, he converted to the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation as the way Platonism can become concrete and effective through the incarnation of the Logos.”

Two men in London have been arrested for stealing a Banksy shortly after it was shared on social media: “The work, featuring three drones overlaid on a traffic sign in Peckham, South London, had been confirmed as a new creation by the anonymous graffiti artist.”

Did you know that the world’s largest Dickens festival takes place in Holland? “Despite no known historical connection with the author, Deventer, in the eastern province of Overijssel, now plays host to what is believed to be the world’s largest Dickens festival . . . Among the expected 125,000 visitors will be Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Queen Victoria, Miss Havisham, beggars, thieves and, for the first time, Dickens himself.”

Dustin Sebell takes stock of the Bronze Age Pervert’s self-published Yale doctoral dissertation:

Costin Alamariu, also known as Bronze Age Pervert, is a minor celebrity on the internet. “A leading cultural figure on the fascist right,” according to a recent profile in The Atlantic, BAP mixes “ultra-far-right politics, unabashed racism, and a deep knowledge of ancient Greece.” But before becoming BAP—the solid, original core of an online subculture with a soft, highly derivative periphery—Alamariu received his doctorate in political science from Yale. This book, “very little” changed from his dissertation, was briefly an Amazon bestseller.

In my admittedly limited experience, Alamariu’s appeal, especially to his young audience, is a complex phenomenon, extending to partisans of both the right and the left. Some of the reasons for his appeal are bad; others are shallow; still others are deep. Alamariu knows his history, and when he merrily recounts the feats once performed by merry bands of men, he thereby reminds you that our world is not the only one possible. There have been other, perhaps better, more ennobling worlds before. Maybe there will be again?

Alamariu thus opens the door to exhilarating and terrible possibilities, possibilities your teachers (popular culture included) either did not dream of or did not want you to dream of. He gives the impression that the only thing stopping you from going through the door is you: your guilt, your fear that you will be struck down by lightning. Once you are through the door, however, no lightning strikes, you breathe a sigh of relief, and he warmly, playfully invites you to take in the crisp, clean air. The old you, by contrast with the new you, looks increasingly like a terrified, guilt-tripped, half-voluntary commitment to an unhygienic, overbureaucratized insane asylum. Overall, Alamariu speaks to his young audience in a way that echoes how, I suspect, Mishima’s longing for the past in all its heights, on the one hand, and Houellebecq’s despair of the present in all its depths, on the other, first spoke to him.

Behind the exhortations or lamentations, however, lies something worth thinking through. Alamariu’s recently self-published dissertation offers an opportunity to do just that.

Joseph Epstein reviews Benjamin Taylor’s biography of Willa Cather: “Chasing Bright Medusas is a splendid book, elegantly formulated, casually authoritative, admirably concise, offering a balanced account of a writer I believe the best American novelist of the past century.”