What's New – And Not So New – In Spy Fiction

John Wilson recommends new works and classics of the genre

For more than twenty years, I’ve ranted against fashionable claims that spy fiction was out of gas, having lost its raison d’être with the end of the Cold War. On the contrary, I maintained, the genre was enjoying rude health, with a mix of grandmasters, solidly established figures, and interesting new voices, and there were more than enough regional and global conflicts to keep spies and spymasters busy and readers turning the pages.

I was right about that. I’m not so sure, though, about what lies ahead. Good books continue to appear, and promising new writers—I’ve mentioned David McCloskey, whose excellent second novel, Moscow X, appeared last fall, and thanks to Nadya Williams at Current, I recently read a very good YA novel, Traitor, by Amanda McCrina, published in 2020. Andrew Klavan’s superb espionage-adjacent Cameron Winter series is going strong (the third book in the sequence, The House of Love and Death, was published last Halloween).

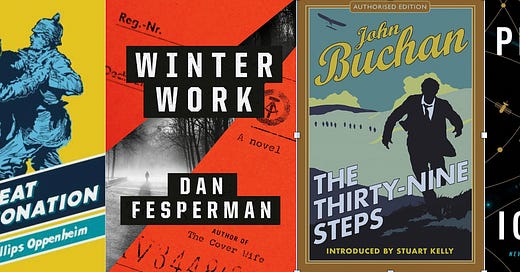

Other writers I’ve followed with pleasure for years continue to produce new work: Dan Fesperman, for instance, whose latest novel was Winter Work (2022). David Ignatius, who has an amazing range of contacts cultivated over the decades in his day-job as a journalist, is especially strong on the evolving technology of espionage; he has a rather clunky style but a strong moral compass. I’m very much looking forward to his new novel, Phantom Orbit, due in May (appealing to my interest in “space” as well as in spies). And there are some not so much to my taste whom I nevertheless read because they seem, to me, to be among the leaders of the pack: Charles Cumming is one, author of the Box 88 series and a number of other novels as well. If I’m not as boosterish about the genre as I unhesitatingly was a decade ago, there are still a lot of good books coming out.

But apart from new books, there are so many already published, some to be revisited, others to be discovered only now. If you haven’t ever read E. Phillips Oppenheim’s 1920 novel The Great Impersonation, you owe it to yourself to give it a try. And John Buchan’s Richard Hannay novels are splendid. I know a fair number of fellow readers who are familiar with The Thirty-Nine Steps, in part thanks to the movie version directed by Alfred Hitchcock, but the entire series of Hannay novels will repay your attention (be sure to read them in order of publication). In this column for July 2023, I wrote about a reread of Eric Ambler then in progress. In the latter stages of that project, after the column had been written, I also read for the first time a couple of novels from the very end of his career; one of these, Doctor Frigo, is superb, though I almost never see it mentioned, and (as I’ve just confessed) I hadn’t read it myself until late last summer, despite being a longtime Ambler fan.

And of course there is also the vast nonfictional literature of espionage, with shelf upon shelf of new titles appearing month after month, year after year. Many fellow readers of spy fiction, I’ve discovered, gobble up this stuff as I do: books such as Anthony Masters’ Literary Agents: The Novelist as Spy (1987, with a foreword by Len Deighton), Gary Bruce’s The Firm: The Inside Story of the Stasi (2010), Robert Service’s Spies and Commissars: The Early Years of the Russian Revolution (2012), and Helen Fry’s Women in Intelligence: The Hidden History of Two World Wars (published late last year, one of a number of espionage-related books by Fry), to name but a handful.

I would be remiss not to mention a delightful oddity: Agents of Treachery (2010), edited by Otto Penzler, with a marquee subtitle: Never Before Published Spy Fiction from Today’s Most Exciting Writers. As Penzler observes in his introduction, thriller-writers and masters of espionage don’t routinely turn their hand to the short story (and this is especially true since the 1950s). This anthology is a welcome rarity, featuring stories by Lee Child, Joseph Finder, Stephen Hunter, Charles McCarry, Dan Fesperman, Stella Rimington, and Olen Steinhauer, among others; my favorite of the distinguished bunch is Andrew Klavan’s “Sleeping with My Assassin.”

I love what Penzler says he told the contributors to this volume: “Write an international espionage or thriller story and set it anywhere in the world you like, in any era. No subject was forbidden, no word length specified, no political position denied, no philosophy advanced or hindered.” Yes, there is a bit of huffing and puffing here (would “no political position denied, no philosophy advanced or hindered” be something to brag about if it were actually put into practice?), but we could use more editors (and publishers) like Penzler in 2024.

Speaking of fiction in 2024, there’s a lot to look forward to in addition to tales of espionage. One of the literary events of the year will be the publication, next week, of Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage? A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress, in which Jessica Hooten Wilson “transcribes, compiles, and organizes” the unfinished novel O’Connor left behind when she died. Wilson’s inspired “work of literary excavation” should start a conversation that lasts a long time.