What Is Kitsch? Why Does It Matter?

Also: Henry James in America, ancient weightlifting, a history of the apple, Marina Abramović as wellness guru, revisiting the Great Siege of Malta, and more.

In the latest issue of Modern Age, Roger Kimball has a long essay on kitsch. The whole thing is worth your time. Kimball doesn’t state this directly, but it clearly follows from his piece that “woke” art can be a kind of kitsch.

Kimball begins by acknowledging that kitsch, of course, is a form of sentimentality:

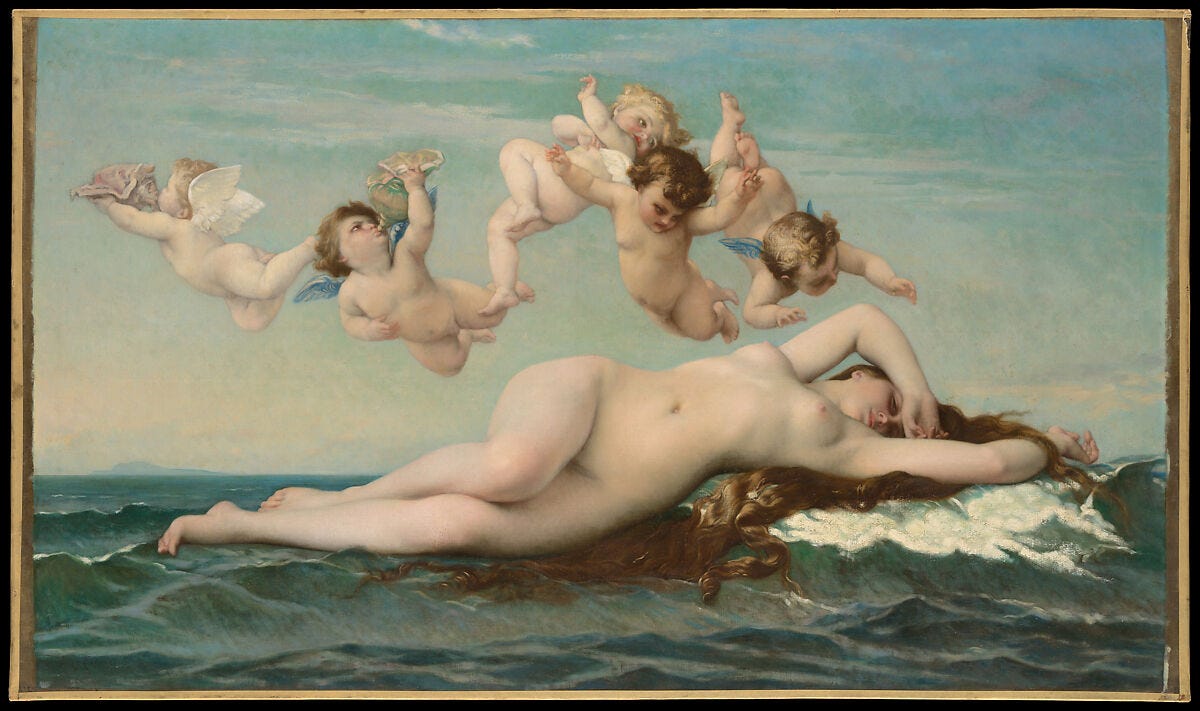

“Kitsch” were picturesque, somewhat sentimental and romanticized celebrations of simple pleasures and country life, forest scenes, and mountain vistas; also kitsch were dramatic portraits of alluring nudes or ethereal lovers, often laced with melancholy, tinged with an exotic religiousness or eroticism. The productions of the French Salon at this time are perhaps paradigmatic, though kitsch has no national allegiance and comes in many varieties: One could turn just as well to the pre-Raphaelites or to the work of Arnold Böcklin. In any case, kitsch served the double function of providing its clients with a vacation from the monotony of everyday life while at the same time managing to indulge their demand for culture and emotional stimulation.

Quickly assimilated and applied to kindred phenomena in other arts, the term acquired an aura of moral censure: Products castigated as kitsch were somehow falsely sentimental, cheaply and dishonestly titillating. The dictionary supports this impression when it defines kitsch, a “sweet, sentimental product of bad taste,” as “characterized by worthless pretentiousness,” artistic “rubbish” that makes “no spiritual or intellectual demands on the viewer” and whose “distinguishing mark is untruthfulness.” Quite a litany. Yet if kitsch is to be more than a term of abuse, we must be able to use it to identify and analyze particular instances of kitsch.

But bad religious and political art are also kinds of kitsch. Here’s how:

Kitsch is always ready to sacrifice the particular for the general, the specific for the universal, the concrete for the abstract . . . Instead of attempting to communicate individual beautiful, true, evil, human phenomena, kitsch strives to incarnate beauty, truth, evil, and humanity without loss. Art is more modest. It sees the universal in the particular, true, but it does not thereby dispense with the particular; its gaze remains focused on the particular because it realizes and accepts that, for man, the world speaks not abstractly or all at once but piecemeal, in fragments, through this tree, this landscape, this face, this web of relationships in which I find myself.

More:

Kitsch, like Romanticism, tends toward idealism. Thus its fondness for grand abstractions, for lofty religious or philosophical themes, for “spiritual” Tristan and Isolde–type relationships. Yet there is something peculiar about this idealism.

Noting Hegel’s observation that “chance and external factors completely determined the material” in traditional genre painting, Berthold Hinz points out in Art in the Third Reich that Nazi art, though indebted to the tradition of genre painting, underwent a telling metamorphosis: “Every child and every cow was now supposed to embody ‘the sacred mysteries of the natural order.’ This meant that children or cows . . . could no longer be what they were.” This transformation is in perfect accord with Hitler’s prescription for a new “German Art” that “shall and will be of eternal value.”

The difference between kitsch, with its idealism and talk of eternal values, and a genuinely religious art emerges when we consider more carefully what kitsch claims. Behind its idealism is the attempt to make the ideal completely available, that is, to render it finite and hence no longer ideal. At the same time, kitsch compounds this confusion by elevating some fragment of reality to an ideal, or pseudo-ideal, status. The great advantage of this double confusion is that the ideal, which is by definition not fully accessible, is now easily grasped and still has the afterglow or aura of ideality.

Fully available, kitsch relieves man of the unhappy necessity of having to confront an ambiguous future with no certain values to guide him; the question, What should I do? is now answered. Nor need man be content with the merely mundane. The aura of ideality that surrounds kitsch continually translates even simple, everyday tasks into cosmic events. Kitsch is thus a kind of idolatry; it refuses to recognize the ideal as ideal but at the same time sentimentalizes some aspect of reality, hoping to find in it a substitute for the lost ideal.

In short, Kitsch provides us with stock characters and ready-made ideas presented in unambiguous forms.

Kimball concludes that kitsch is a result of the collapse of “traditional value structures”:

In kitsch we see mirrored the spiritual situation of our age. This is what leads Orwell to diagnose Dalí as “a symptom of the world’s illness” and Nietzsche to interpret Wagner first of all as epitomizing modernity: “Through Wagner modernity speaks most intimately”; Wagner is the “modern artist par excellence,” purveying “all that the modern world requires most urgently.”

What is it about modernity that breeds kitsch? And what is the need that kitsch fulfills? Orwell looks to the “perversion of instinct that has been made possible by the machine age,” while Nietzsche points to an awareness of the homeless, fragmentary character of modern life together with a refusal to acknowledge that same reality.

Wherever we look for its origin—in the social upheavals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries or, with Nietzsche, in the subjectivism that underlies the “Copernican” turn of modern society—kitsch appears as an attempt to deny the insecurity that attends the collapse of traditional value structures. If modernity bequeathed man a new freedom, this freedom brought with it a new homelessness. Kitsch bears witness to man’s desire for home.

The lesson here is that a defense of “traditional value structures” is no match for kitsch. One must respond with better art—a lesson that conservatives have mostly missed.

In other news, Peter Rose writes about Henry James’s return to America in Literary Review:

In 1904, Henry James decided to return to America. He was feeling isolated at Lamb House in Rye. In a letter to Grace Norton, he wrote: ‘The days depart and pass, laden somehow like processional camels – across the desert of one’s solitude.’ Since the flop of Guy Domville, his dreams of success as a dramatist had been dashed. The Wings of the Dove had been published in 1902, followed by The Ambassadors in 1903, in serial form. The Golden Bowl – written in little more than a year and, for many, his sovereign achievement – was almost finished. Now, after this awesome outpouring, he was ready to review his homeland, last visited in 1882.

James’s reasons for returning were complex, some obvious and professional, others psychological and obscure. Family drew him back, just as it had subtly hurried him on his way in 1875, when he left America, first for Paris, then for London. Planning his itinerary, James wrote to his nephew Harry: ‘I can’t tell you how I thank you for offering me your manly breast to hurl myself upon in the event of my alighting on the New York dock, four or five weeks hence, in abject and craven terror.’

“Who was the real Émile Zola?” Alexander Lee attempts an answer in The Critic:

No-one had a keener eye for Émile Zola than Cézanne. And no wonder. They were boyhood friends. Having grown up together in Aix-en-Provence, they kept up a lively — at times, even faintly homoerotic — correspondence even long after they had both become famous.

Over the years, Cézanne drew or painted the novelist several times; but perhaps his most revealing portrait is now in the São Paulo Museum of Art. Painted in 1869/70 — just as Zola was embarking on the vast Rougon-Macquart series of novels — it is really a double portrait. On the left sits Paul Alexis, a young journalist, who had recently arrived in Paris from Provence, and who would go on to become Zola’s first biographer. He is reading aloud from a manuscript, with his legs crossed nervously under his chair.

Meanwhile, Zola sits — or rather, reclines — on the right. He has an almost Buddha-like calm. His brow is furrowed slightly; his lips pursed in thought. But his gaze remains inscrutable. What he thinks, or how he feels, is a mystery.

Ancient weightlifting: “The earliest evidence of weightlifting in the ancient Greek world is a sandstone block from Olympia, weighing about 315 pounds, with a pair of deep, smooth grooves worn into the long top side of the stone. The grooves make it possible to picture the event described by the words cut into the rock: ‘Bybon, son of Phorys, lifted me over his head with one hand.’ A similar inscription can be found on a bigger, heavier rock, hundreds of miles away on the island of Santorini. Seven feet long, six feet in circumference, the black volcanic boulder weighs more than 920 pounds and bears this chiseled announcement: ‘Eumastas, the son of Critobulus, lifted me from the ground.’ Many classicists have been skeptical of the boasts carved on these stones . . . Nigel Crowther, the only classicist of that era who had been a competitive powerlifter . . . contended that both ancient claims are plausible.”

Among the many grievances aired by Norman Podhoretz in his insufferable 1967 memoir Making It is an already septic grudge concerning The New Yorker’s publication of James Baldwin’s most famous essay in 1962. Titled, following the magazine’s convention, “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” this twenty-thousand word assemblage of memoir, reportage, and philosophical interrogation of the American condition that has become Baldwin’s rhetorical signature was filed by Baldwin as “Down at the Cross,” the name it would retain when reprinted the next year as the second part of The Fire Next Time. According to Podhoretz, not long after succeeding Eliot Cohen in the wake of the founding editor’s suicide, he commissioned Baldwin to write a piece on the Nation of Islam, whose ascendance in New York alongside the sect’s most prominent minister, Malcolm X, was disconcerting the magazine’s white, liberal, and mostly Jewish readership. Around the same time, The New Yorker asked Baldwin for a dispatch from Africa, then in the midst of postcolonial revolt. In 1958, longtime fiction editor William Maxwell, an admirer of Baldwin’s first book of essays, Notes of a Native Son, collected from contributions to Commentary, The New Leader, The Reporter, Partisan Review, and Harper’s, had solicited Baldwin for unpublished work, and in July 1961, then-New Yorker EIC William Shawn signed a series of letters addressed to the authorities in the Congo, Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, and Guinea identifying Baldwin as a New Yorker correspondent.

Though the trip to Africa, via Istanbul — where Baldwin resided throughout his life, when not living in France or his native New York — and Israel, came to fruition, the New Yorker assignment did not. His sense that, as an American, he had both too little and too much to say about the continent, which he detailed in letters to his agent, Robert Mills (later published in Harper’s as “Letters from a Journey”), weighed on him, as did the $5,500 advance — more than $58,000 in today’s currency — that he had received from the most prestigious outlet of literary journalism, and which he had likely already spent. Baldwin followed through on the Commentary assignment to a point, traveling to Chicago to interview Elijah Muhammad, but when Podhoretz requested the manuscript, Baldwin turned cagey: he didn’t have it, and neither did Mills. Instead, it was on Shawn’s desk, where, Baldwin insisted, rejection was imminent, upon which all eighty-one pages would be duly forwarded to Commentary, excusing this unexpected detour as a goodwill gesture of contrition for past negligence, with a whiff of noblesse oblige. Podhoretz knew that Shawn’s budget and distribution far exceeded his own (Baldwin’s last review for Commentary, of Otto Preminger’s Porgy and Bess, paid only $100), not to mention the triumphant significance of a New Yorker acceptance to any writer’s career. Unsurprisingly, given the essay’s genius, Shawn approved, reserving most of the November 17 issue for its inclusion, and sending along another check for $6,500. The hefty advance was not the only uncharacteristic aspect of Shawn’s decision, as Ben Yagoda notes in About Town: “Down at the Cross” was the New Yorker’s first elaborate treatment on the subject of race, and eluded the established rubrics of the magazine, which was not then in the habit of publishing essays of opinion. It is what eventually inspired Shawn to introduce a “Reflections” section. When Dial Press republished the essay in 1963, appended by “A Letter to My Nephew,” initially purchased by The Progressive, Baldwin earned another $65,000 — for one essay and a brief, if unforgettable introduction, just shy of $800,000 in 2025.

Marina Abramović, wellness guru:

“Marina Abramović: Transforming Energy,” at the Modern Art Museum (MAM) Shanghai, boasts 150 works over three floors, including many crystal-based sculptures nodding to her interest in Eastern medicine. Some of the pieces resemble a cross between furniture and something more ominous. There are wooden beds with large crystals pointed at the head; copper tubs with crystals pointed where a faucet might be; deck chairs facing metronomes; doorways with crystals mounted on every surface . . . She doesn’t consider them sculptures because the object is not the point; the energy is.

The writer doesn’t mean this as a critique of Abramović’s work, but it is unintentionally scathing.

A history of the apple: “What we think of as an apple today – the sweet Japanese Fuji, the American picture-book Red Delicious or the sharper, Brit-friendly Cox or Bramley – owes its gamut of qualities to an easygoing readiness to adapt to local conditions. Coulthard’s story begins with the ancient ancestor of the Gala and Granny Smith, which hitchhiked west from the wild apple forests of the Kazakhstan mountains, promiscuously mixing with local crab apples along the way. The resulting hybrids produced fruit with qualities we still appreciate – sweetness and acidity, texture, disease-resistance and storability – and sweetened lives and flavored cultures as they traveled. Greeks, Romans, Norse and Celts rooted their fertility myths in the apple’s embrace. Milton retrofitted the apple to the Bible’s generic ‘fruit of the tree of knowledge,’ making the most of the Latin malus for apple and evil.”

Revisiting the Great Siege of Malta: “‘Was it really the greatest siege?’ Catherine de Medici asked. ‘Greater even than Rhodes?’ ‘Yes, madame,’ the knight commander Antoine de La Roche answered, ‘greater even than Rhodes. It was the greatest siege in history.’ . . . Is this reputation deserved? Is the whole bloody episode as significant as, for example, the second siege of Malta in 1940, when German and Italian bombers pounded the little island for two and a half years, earning it the George Cross? Bull interrogates the myth relentlessly but not unfairly, trying always to set the story in both its contemporary global context and its place in history. His cool findings do not diminish the savagery and bloodshed, or the heroism displayed on both sides, but they do make the proceedings seem peculiar, to put it mildly.”

Peter Quinn reviews James Chappel’s Golden Years: How Americans Invented and Reinvented Old Age:

Chappel credits the Depression with pushing the issue of pensions to the forefront. Huey Long, the demagogic governor of Louisiana, proposed pensions of thirty dollars a month (seven hundred dollars in today’s money) for everyone over sixty. Upton Sinclair, the socialist candidate for governor of California, proposed fifty dollars a month.

Little remembered today, California physician Francis Townsend inspired one of the “largest and most active social movements in the first half of the twentieth century.” His idea was to distribute two hundred dollars per month (almost five thousand dollars today) to every American over sixty regardless of race, gender, or marital status. He sought to save the elderly from turning for help to family, charity, or, as Blanche DuBois lamented, “the kindness of strangers.” The one condition was that recipients spend all their allotment by the end of the month. Townsend “wanted older people to spend money and have fun doing it; he envisioned older people driving cars and hitting the town,” Chappel writes. His vision of old age flew in the face of time-honored Puritan notions of the end of life as a time of sober reflection and repentance in preparation for the final judgment.

In praise of not reading alone: “History shows that reading at its best used to be much more communal than individual—because the function of the earliest literature was to bring people together rather than give them a delight to hoard all to themselves.”

Close to 10:30pm when I finally found the time to read this excellent issue! Now I face tomorrow with the task to click through almost every offered link. It’s an almost overwhelming surfeit of literary treasure! And I thought kitsch was a portrait of Jesus on black velvet. If “The Birth of Venus” is kitsch I want more!