Wednesday Links

Two new literary publications, common sense on book bans, the lasting appeal of Charles Villiers Stanford’s church music, and more.

Good morning! In the new online (and eventually print) magazine The Metropolitan Review, Tara Isabella Burton reviews Gabriel Bump’s semi-dystopian novel The New Naturals. Why “semi-dystopian”? Well: “We can never escape the world. Nor can we remake it. This truism underscores all great would-be utopian novels, from Samuel Butler’s 1872 Erewhon — an anagram of ‘nowhere’ — to dystopias proper like Brave New World and 1984, to failed-cult novels like Emma Cline’s The Girls. Any attempt to lift a few, quixotic human beings out of the psychosocial morass of human nature — be it in a monastery or on a compound, on a remote island or in a new world order — is doomed to fail, for one reason or another . . . Gabriel Bump’s The New Naturals, a lyrical but overly mannered entrant into the annals of false utopias, seems reasonably confident in its assessment of the first question . . . Bump has less to say about human nature, temporal or eternal, than he does about, well, all this. In so doing, he renders The New Naturals, like the commune itself, too small in scope. It is a powerful story of contemporary America. That this America might be made up of people, rather than powers, lies beyond the horizon of the narrative.”

Speaking of new magazines, David Bahr and Declan Leary have started a print-only quarterly called Lyceum. It looks like it will publish new pieces alongside older work like the still shuttered Lapham’s Quarterly.

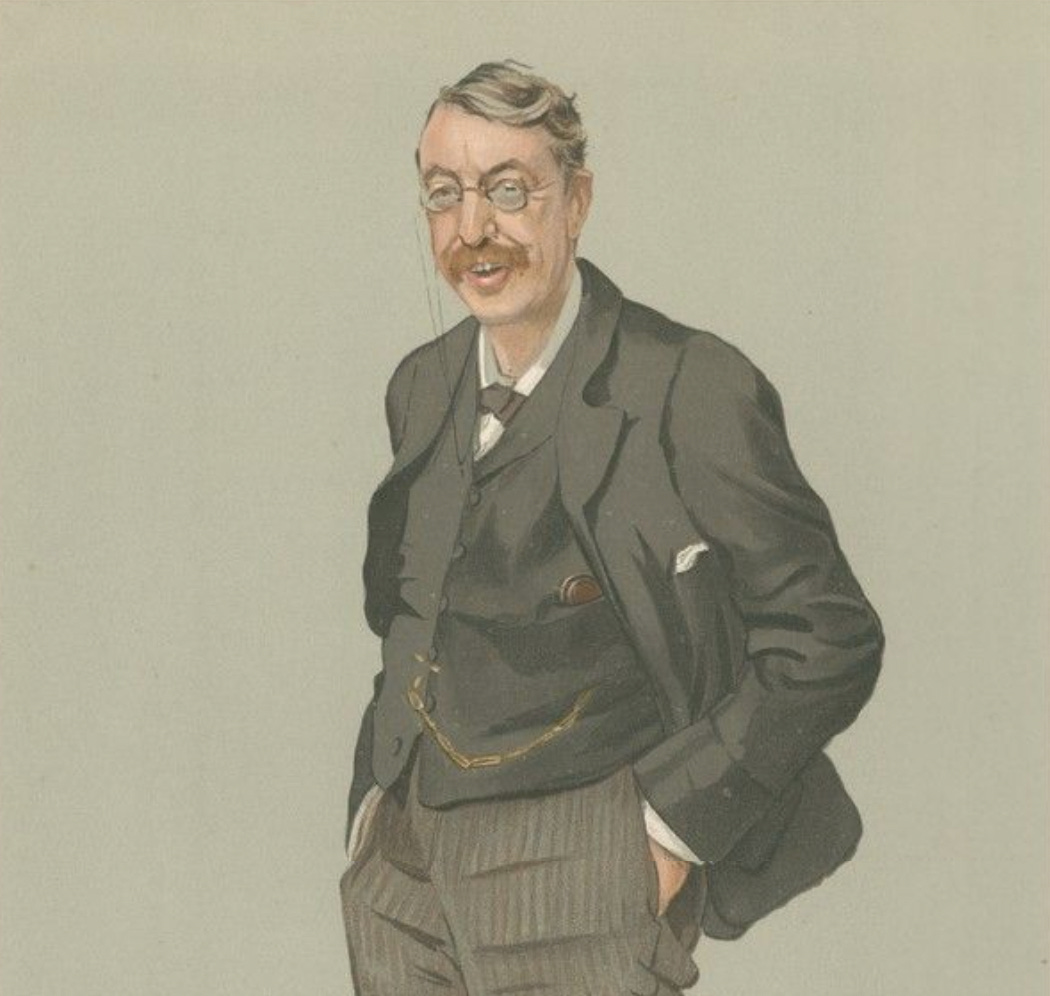

Peter Phillips revisits the life and work of the composer Charles Villiers Stanford:

Stanford was among the first composers in Britain to write church music that was not automatically relegated to the background; and it was Stanford who, through being professor of music at both Cambridge and the Royal College of Music in London (at the same time) raised the teaching of music at university to put it on a par with other more respected subjects. Most remarkable was his fluency as a composer. Jeremy Dibble’s newly revised biography has a list of his complete works, which runs to 43 pages: seven symphonies, nine operas, four piano concertos, three violin concertos, one concerto each for cello and clarinet, five organ sonatas, eight string quartets and many sonatas for piano and strings, other songs and miscellaneous chamber music without number. It is ironic that the section dedicated to his liturgical Anglican music – the only body of his music regularly performed today – is one of the shortest. His current reputation rests on two Evening Services (in F and E flat), six more Morning, Communion and Evening Services (in B flat, A, F, G, C and D), 25 anthems, four mass-settings, a Latin double-choir Magnificat and various carols and hymn tunes.

We can see with hindsight that Stanford’s greatest achievement as a composer was to write, at just the right historical moment, the kind of Anglican service music that appealed to the churchgoers of his time, an appeal which has lasted. For more than a hundred years this repertoire has been found to have just the right mix of academic solidity, catchy melodies, unthreatening harmonies and effective sweep. It is worth underlining that this renaissance owed nothing to the German performance tradition, which was based in the teaching at conservatoires. It was a specifically British event, rooted in the practice of robed choirs of men and children, singing almost daily in at least 35 foundations around the country. This practice has continued to the present day – despite the lack of a strong religious sensibility in the public and the inevitable shortage of cash – and has been extended recently to involve girl choristers alongside the boys, so enhancing its unique educational value. Evensong has become more of a cultural icon than a religious event. As Richard Dawkins, no theist, put it, ‘I’m a cultural Anglican and I see evensong in a country church through much the same eyes as I see a village cricket match on the village green.’

Asher Gelzer-Govatos writes in praise of Sergiu Celibidache conducting Anton Bruckner:

As a general principle, I avoid fussiness in my choice of symphony recordings and aspire to omnivorism in my listening diet. Some regard Bernstein as a bowdlerizer; I find him charmingly energetic. And I am just as happy to listen to him conduct the New York Philharmonic in the finale of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony at his blistering pace as I am to cherish Yevgeny Mravinsky’s slow, austere rendition with the Leningrad Philharmonic. Vive la différence.

Yet I have one gigantic, overriding exception. Anytime I want to listen to a Bruckner symphony, which, for me, is usually two to three times a week, I turn first to any recording made of Sergiu Celibidache. My preference is contrarian in two ways. Bruckner’s symphonies are decidedly an acquired taste, and Celibidache has a certain infamy in classical music circles as well. When I type his name into the YouTube search bar, one of the first results I get is a takedown video titled “Sergiu Celibidache—Mad Perhaps, but A Genius? Not.”

Taken together, Bruckner and Celibidache are a forbidding combination. Celibidache’s unhurried tempos stretch the already slow-building structure of Bruckner’s symphonies to the breaking point. A typical Celibidache recording will be somewhere around fifteen minutes longer than the average recording by another conductor. Considering that Bruckner’s symphonies already log in at over an hour each, this pace tests the patience of many. For a certain sliver of the listening public, though, myself very much included, Celibidache’s performances of Bruckner’s symphonies—well, Symphonies Three through Nine, as he never deigned to conduct the first two or the composer-renounced “Zero”—have attained something of a cult status. The match is perfect.

The Department of Education has dismissed 11 complaints against book bans. It is also eliminating the position of “book ban coordinator”: “‘By dismissing these complaints and eliminating the position and authorities of a so-called “book ban coordinator,” the department is beginning the process of restoring the fundamental rights of parents to direct their children’s education,’ said Acting Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Craig Trainor. ‘The department adheres to the deeply rooted American principle that local control over public education best allows parents and teachers alike to assess the educational needs of their children and communities. Parents and school boards have broad discretion to fulfill that important responsibility. These decisions will no longer be second-guessed by the Office for Civil Rights at the U.S. Department of Education.”

Longtime readers of this email will know that I am in favor of such a move. I have argued that book bans are overhyped—they are not that frequent and are mostly motivated by common-sense concerns about age-appropriate material.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Prufrock to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.