Wednesday Links

William Boyd’s new spy novel, the end of “scenius,” Versailles’s scientists, Martin Amis’s “Money,” and much more.

Good morning! The Washington Free Beacon only publishes two or three reviews every weekend, but they are usually excellent. This past weekend was no exception. Alexander Larman reviews William Boyd’s new spy novel, Gabriel’s Moon: “William Boyd has been one of literature’s great purveyors of what you might call the thumping good yarn ever since his first novel, 1981’s A Good Man in Africa, cannily updated Evelyn Waugh’s distinctly un-woke but hilarious fiction for a contemporary audience. Ever since then, his superbly written, ceaselessly engaging books remain some of the most reliable pleasures to be found on any bookshelf, anywhere. Over the past few years, Boyd has settled into two main modes of storytelling. The first is the so-called whole-life novel, in which he follows an individual over the course of their entire existence; a literary form that he pioneered with 1987’s The New Confessions, perfected with his 2002 masterpiece Any Human Heart, and has since revisited several times, most recently in 2022’s The Romantic. And the other is the spy novel, which Boyd, for my money, does as well or better than any living writer. Gabriel’s Moon, the first in what Boyd has suggested will be an ongoing series, is most definitely a spy novel of the Buchan-esque school.”

Reuel Marc Gerecht, on the other hand, reviews a history of the CIA that is not quite fiction and yet unintentionally thrilling:

Hugh Wilford, a professor of history at California State University, Long Beach, is an established left-wing commentator on the agency, whose earlier books, America’s Great Game: The CIA’s Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle East and The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America, established the theme and style of his most recent work, The CIA: An Imperial History. One could summarize the sentiments and narratives of all these works: The CIA has rarely been a force for good in this world; individual officers may mean well, but they are all doomed, by temperament, education, and mistaken analysis of the real and imagined threats against the United States, to march through history cocking up, bringing more shame than honor to the nation, sometimes debasing democracy at home while continuously inflicting a lot of misery upon “the Global South.”

As a former case officer, I get a certain frisson from these books. Langley, as an institution, actually doesn’t mind them either because, no matter how notorious the depiction, the CIA matters in these stories. They all conjure up an intelligence service with enormous history-shaping agency. The duller, more depressing truth about Langley: In most places throughout the Cold War its influence was far less than what the CIA and Wilford want you to believe. My more talented classmates, who all came into the CIA when Bill Casey was the director, used to have this running joke about finding “Big Brain”—the hidden outposts of the “real” CIA, where first-rate officers did first-rate things. Most of us would have been thrilled to discover even a wicked Big Brain—the type of Third-World-shaking nefariousness that Wilford spends most of his energy on.

How did Greenwich Village become the bohemian capital of America? Mathew Gasda explains in a review of David Browne’s Talkin' Greenwich Village: The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America's Bohemian Music Capital:

Reading David Browne’s Talkin’ Greenwich Village helped me make sense of my own experience as a romantic young artist in New York who was driven not only by nostalgia, but by a deep need for artistic community. The book, essentially a constellation of biographies of key Village musicians (Dave Van Ronk, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins, Peter, Paul and Mary, Eric Andersen, Phil Ochs, Joni Mitchell, Suze Rotolo, The Roches, National Lampoon, and Suzanne Vega) that also touches on the history of spaces (Kettle of Fish, Café Wha?, The Gaslight, Café Au Go Go, the Blues Project, Blue Note, The Bitter End, and the Village Vanguard), demonstrates that bohemians and bohemia are symbiotic: The place and the people co-create each other when the underlying conditions are right.

The Village had all the ingredients of a perfect urban ecosystem: charming old-world architecture, deep history, and a multiethnic character; affordable rent, a working-class Italian community that resisted rapid gentrification; ample public space (Washington Square Park), and a robust network of platforms for artistic expression. It resisted exploitation, mass demolition, and unchecked gentrification for much of the twentieth century. It had just enough charm and architectural dignity to be appealing, situated in Lower Manhattan, yet it remained a little too violent and working-class to draw the wealthiest mid-century elite.

The Village was rough and beautiful. It was jazz and folk, black and white, gay and straight. A pedestrian walking down MacDougal Street in the early 1960s would hear a cacophony of “strumming, coffee machines, and smatterings of applause” from coffeehouses and clubs. It was a place where a young Ornette Coleman could “dyna[mite] known boundaries,” and young folkies from out of town could enter a “more liberating world” just by knocking on the right door (often that of Village fixture, guitar teacher, and blues singer Dave Van Ronk).

Ian Leslie writes about the importance of writers and artists living in close proximity to one another and why it may be a thing of the past:

Brian Eno coined the term “scenius” to refer to the collective genius that can emerge when a population of diverse and fertile talents living in geographical proximity to other form a loose community or ‘scene’ . . . Throughout history, urban scenes like this have repeatedly proved fertile: Renaissance Florence, of course, and Elizabethan London; Vienna in the late nineteenth century; Montmartre in the early twentieth century; Harlem in the 1920s; London in the 1960s; Seattle in the 1990s, and many others (periods and cities). Much of what we now treasure, culturally speaking, was forged inside these metropolitan concatenations.

There’s something about living and working near other artists and art-adjacent people that multiplies individual potential. This is a measurable phenomenon: a study of classical composers during the period 1750-1899, in Paris, Vienna and London, discovered that they were significantly more productive when they lived in close proximity to other composers. Notably, it was the most talented composers who benefited the most.

You can guess at the reasons: the stimulation of seeing what others are up to, the headspinning conversations, the clashes of different perspectives - creative, theoretical, commercial. Ted Gioia identifies a deliciously darker reason too: rivalry. When your rival (or as Ted prefers, nemesis) is in your geographic and social domain, you are more likely to be annoyed, enraged, and stimulated by them. Above all, perhaps, creative clustering sharpens focus, forging a sense of shared purpose and passion. Density generates intensity.

More:

What was the last musical movement to be distinctively associated with a city in Britain? Trip-hop, from Bristol? Grime, from East London? Once you get beyond 2010 it’s hard to think of any. In the US, New York is a more liveable city than it was for much of the twentieth century, and a less creative one. Portland and Austin are not quite what they were. San Francisco and Silicon Valley are perhaps the last examples of scenius, but those scenes are driven by money, not art.

What killed scenius? Well, as on the Orient Express, there are multiple culprits, but they include the vast inflation of real estate prices in Western cities. Artists made SoHo and Shoreditch attractive places to live, which means that they, or their successors, can’t afford to live or work there. There are fewer and fewer affordable pockets of the city for artists to flee to; once Peckham and Williamsburg are out of reach, where do you go?

Another reason is that the modern internet has made young people more solitary and homebound, and less likely to meet up in shared spaces. In a new article for the Atlantic, Derek Thompson details how Americans of all ages are spending more time at home, and young people are less likely to socialise with friends, trends that were greatly accelerated by the pandemic. Young people are less likely to drink alcohol or do drugs than previous generations, which is good for their health but not necessarily for their artistic vitality.

An Argentine novelist takes on #MeToo: Andrea Moncada reviews Pola Olioxarac’s new book:

In her latest book, which levels a critique against “progressive feminism,” Argentine novelist Pola Oloixarac recounts an episode of brutal gender violence that took place in her own family. Her great-aunt Ana was beaten to death at her doorstep by her boyfriend, in front of her neighbors, in Lima in 1956.

Stories like this one remain common in Latin America—and have galvanized feminist movements to take to the streets. Oloixarac acknowledges the severity of gender violence in Latin America, but in Bad hombre, a “work of fiction about real events,” her attention is mostly directed at a different phenomenon: the reckoning over sexual harassment and assault that spread through workplaces and social circles across the globe in the wake of the #MeToo movement in the U.S.

In doing so, Oloixarac makes the provocative allegation that elite women exploit feminism to serve their own personal interests. “Is it fair,” she writes, “to use Ana’s suffering and those of so many murdered women as a virtuous alibi that conceals personal revenge?”

How Balzac made (or ruined?) the contemporary novel:

In 1842, with eight highly productive years of writing still ahead of him, Balzac wrote a preface to his Comédie humaine, which already comprised dozens of books. He defended the morality of the work, and revealed the scale of his ambition – nothing less than the creation of a complete picture of France in his time. As if wanting some credit, he remarked that it ‘was no small task to depict the two or three thousand conspicuous types of a period’. (This wasn’t hyperbole, since there are more than two thousand named characters in the Comédie humaine.) Balzac’s significance in the history of the novel was fully apparent by 1905, when Henry James said that his ‘achievement remains one of the most inscrutable, one of the unfathomable, final facts in the history of art’.

Of course, not all Balzac’s contemporaries agreed on the quality of the work; some complained that his prose was often rough, accumulative rather than sculpted, the stories often resembling untidy heaps rather than finished monuments. Flaubert, writing to Louise Colet in one of his majestically snobbish moods, declared that ‘Balzac was no writer, merely a man of ideas and of observation; he saw everything, but he didn’t know how to express anything.’ Flaubert was right about Balzac seeing everything, but he doesn’t seem to have realised how important this was. The nature of Balzac’s legacy can be debated, but part of his achievement was to shift the novel in the direction of cultural documentation and analysis.

Madison Smartt Bell reviews The First and Last King of Haiti: “Daut’s book is not a good introduction to the Haitian Revolution. She offers a wealth of fresh detail, but other recent works (e.g., Avengers of the New World, by Laurent Dubois; The Haitian Revolution: A Documentary History, by David Geggus; and A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution, by Jeremy D. Popkin) provide more comprehensive accounts of everything that happened on the island between 1791 and 1804. As a narrative of the rise and fall of Henry Christophe, however, Daut’s First and Last King of Haiti (largely uncritical though it may be) will likely stand as the definitive work for a long time to come.

Versailles’s scientists: “When we think of Versailles, we think of Marie Antoinette, opulence, and the last hurrah of the aristocratic high life before the French Revolution put an end to such folly in 1789. We may also think of philosophers like Voltaire and the age of the enlightenment, but less well-known is the palace’s crucial role in supporting the sciences. As a new exhibition, ‘Versailles: Science and Splendour’ at the Science Museum in London until April 21, 2025, shows, the French court was motivated to sponsor scientific research as a means of consolidating power and expanding colonial rule.”

Noah Millman explains why he hates The Brutalist: “I am struggling to recall a film that made me as angry as The Brutalist did. The top-tier contender for Academy Awards Best Picture directed by Brady Corbet and starring Adrien Brody as the fictional modernist architect László Tóth, who survives the Holocaust, comes to America after the war, toils in undeserved obscurity until being plucked therefrom by a wealthy industrialist who commissions him to build a complex that will make his name enraged me in a way that is entirely out of proportion to the ultimate significance of the film—or, arguably, of any film . . . I know it has something to do with both the level and type of praise that the film has garnered, which I feel is entirely undeserved. The Brutalist isn’t just being called a powerful or important film; it’s being called an epic, a monumental achievement, a landmark. Myself, I found it poorly written, dull, and massively overlong, but also the opposite of epic, both small-scaled and small-souled. But I don’t think the degree of my disagreement is the whole reason or even a particularly central reason for my rage. It’s not just that I think the emperor has no clothes. It’s that I think he’s prancing around naked and urinating in our faces.”

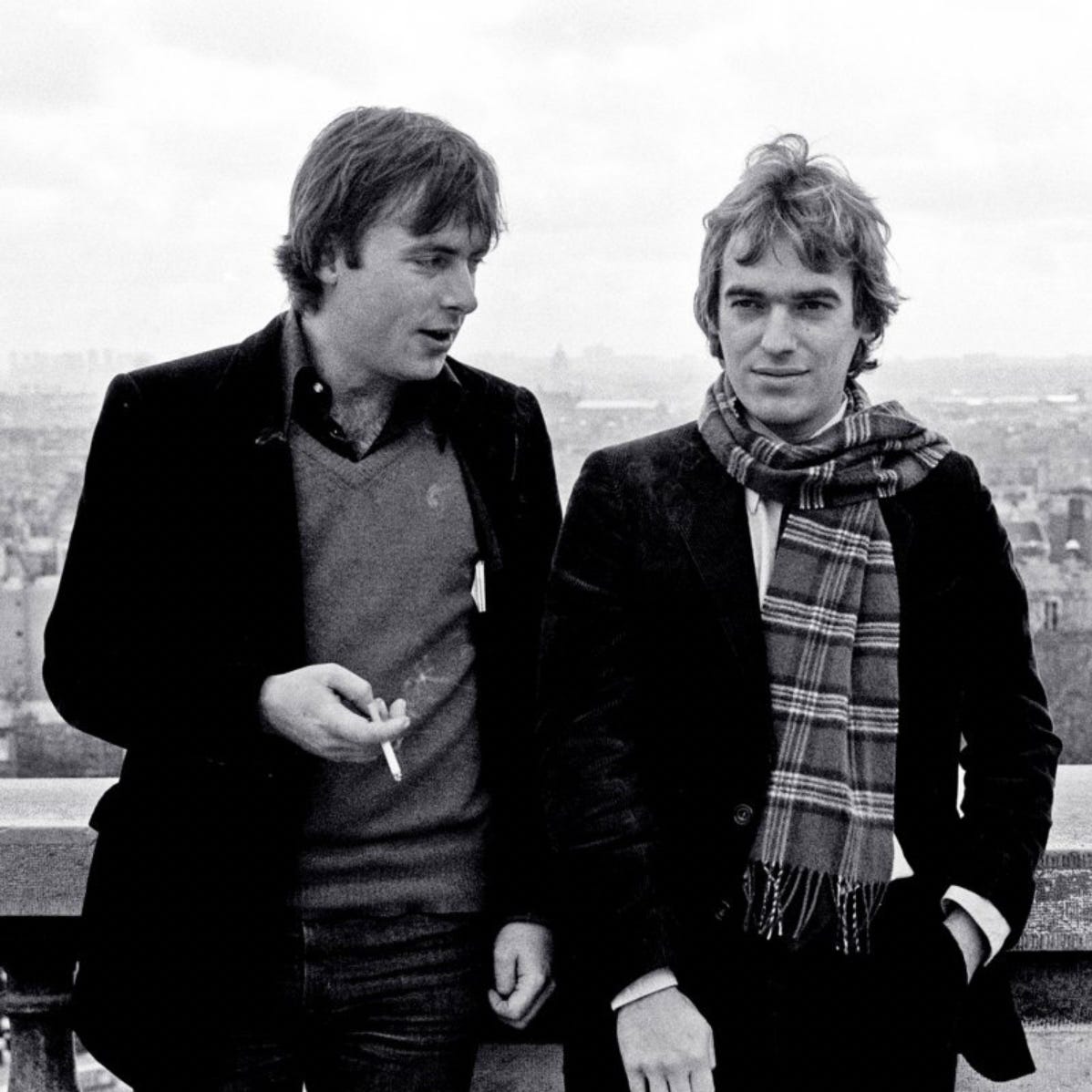

David Herman writes about the significance of Martin Amis in Salmagundi:

Midnight’s Children sold over one million copies in the UK alone and not only won the 1981 Booker Prize but was awarded the ‘Booker of Bookers’ Prize in 1993 and 2008 to celebrate the 25th and 40th anniversaries of the Booker Prize. Amis’s Money, his breakthrough novel, sold 40,000 copies in hardback and nearly a quarter of a million copies in paperback. Ishiguro’s Remains of the Day sold over a million copies and was of course made into a brilliant film by Merchant-Ivory, starring Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson.

But, above all, it was Amis’s voice which stood out. His piece in Granta begins in New York, “off FDR Drive, somewhere in the early Hundreds…. [A] low-slung Tomahawk full of black guys came sharking out of lane, sliding off to the right across our bows.” Say what you like about Iris Murdoch, Angus Wilson and Penelope Fitzgerald (all born before 1920), but they didn’t write much about “low-slung Tomahawks full of black guys.” With Amis came a new kind of literary voice, and a public whose taste for it was rapidly inspired . . . Twelve years before that issue of Granta, in 1971, Amis’s friend and literary father-figure, Saul Bellow was one of the judges of Britain’s leading literary prize, the Booker. The two main contenders that year were VS Naipaul, for In a Free State, and Elizabeth Taylor, whose novel Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, was favoured by two of the judges, the popular historian Antonia Fraser and John Gross, later editor of The Times Literary Supplement. As Gross later recalled, it was Bellow who “pretty much blew her [Taylor] out of the water. He said when the first round came … ‘This is an elegant tinkling teacup novel of the kind that you Brits do very well, but it’s not serious stuff!” One way of summing up the impact of that issue of Granta and of Amis’s Money was that it marked the end of the British “elegant tinkling teacup novel.” Lisa Allardice wrote in her obituary of Amis last year, “Where the literary world had been grey and tweedy, presided over by ageing grandees (Amis Sr, William Golding, Anthony Burgess, Iris Murdoch), now it was young and outrageously brash, and Amis was the frontman.”

Amis’s novel didn’t mark the end of anything, of course, but read the whole piece anyway for its details.

Strange but true: A French woman gives over 800,000 Euros to a fake Brad Pitt. A cave painting is stolen in Mexico.