Thirteen Ways of Looking at Tyranny

John Wilson recommends Ismail Kadare's latest novel, as well as works by Rhonda Ortiz and Andrew Klavan.

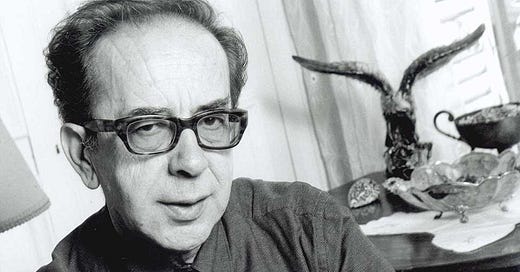

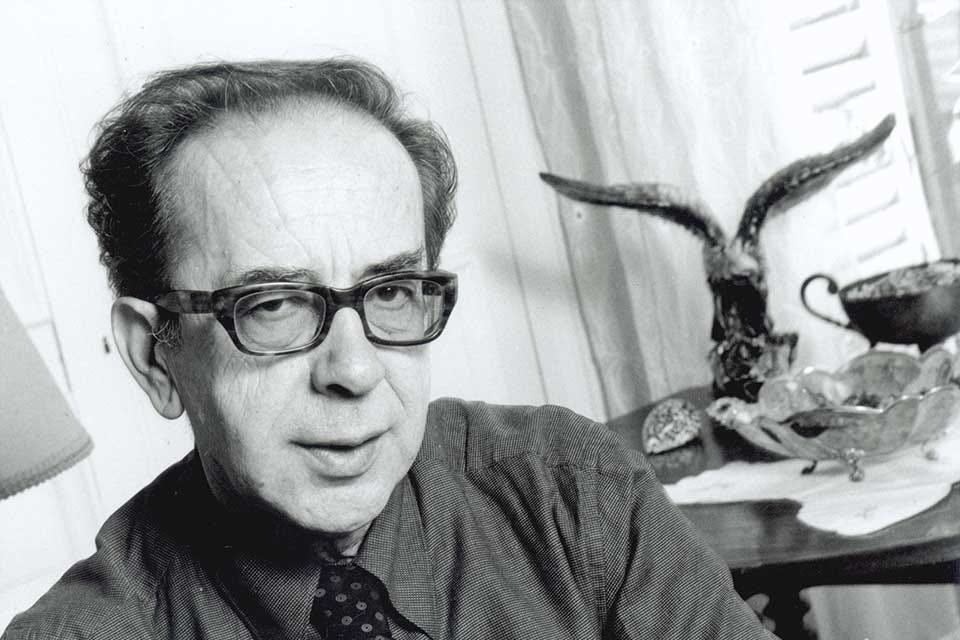

There are a few novelists for whom I am a completist. I have read all their novels, some more than once, and always eagerly read each newly published work. The Albanian writer Ismail Kadare is one.

He is not only a novelist, but that is his specialty, so to speak. If, like me, you follow the annual conversations and speculation leading up to the Nobel Prize in Literature each year, you will have seen his name mentioned as a possible choice (for at least a decade, a while back, it seemed likely that sooner or later he was bound to be chosen). When I talk about him with bookish friends, most of whom have never read him, that is what they usually recall.

This month, Counterpoint is publishing A Dictator Calls, a novel translated from Albanian by John Hodgson, who has brought many of Kadare’s books into English. Its point of departure is the infamous telephone call Josef Stalin is said to have made to Boris Pasternak in 1934, not long after Osip Mandelstam had been arrested. Mandelstam had written a short poem, not published but widely circulated, attacking Stalin. After interrogation and torture, he was released and granted “internal exile” in the Ural Mountains region with his wife, Nadezhda. Three years later, he was rearrested and sent to the gulag, where he died.

Kadare’s infinitely twisty novel, narrated by an Albanian writer who bears a resemblance to Kadare himself, circles around the conversation between Stalin and Pasternak (supposedly quite brief, just three minutes or so, and “reported” over the decades by various sources). It approaches it in thirteen “versions” or scenarios set into play by the subject at various moments in time, ranging from the 1930s to the second decade of our century. These are often only loosely connected to the originating conversation. Enver Hoxha, the notoriously cruel and long-lived dictator who made Albania the last bastion of Stalinism, appears here, but so does Helen of Troy.

If, like me, you are a longtime admirer of Kadare, you are no doubt planning to read this novel. It will repay your attention. But if you haven’t yet tried Kadare, I don’t think this is the one to start with, though you’ll certainly want to read it if (as I hope) he turns out to be your cup of tea.

Among my favorite books of 2018 was Kadare’s novel The Traitor’s Niche. My favorite among his many books is The File on H., set in the 1930s, a novel loosely inspired by research into the “oral literature” still surviving in the Balkans at that time—scholarship which among other things had a lasting impact on our understanding of Homer and his epics. (Think especially of the famous work conducted by Milman Parry and Albert Lord.) The novel brilliantly combines disparate elements that might seem incompatible; matter-of-factness, farce, and the uncanny go hand-in-hand.

(If reading Kadare makes you curious to learn more about the history of Albania (his books have a way of doing that), let me recommend Noel Malcolm's tour de force, Rebels, Believers, and Survivors: Studies in the History of the Albanians, published in 2020 (to insufficient acclaim) by Oxford University Press.)

Sometime in the next several months I plan to devote a column to “historical fiction.” In the meantime, I want to recommend a just-published novel, Adrift, by Rhonda Ortiz, the second book in a planned trilogy (the “Molly Chase Series”). The first book in the series, In Pieces, was published in 2021; its story commences in 1793. Espionage, romance, and quotidian experience in the early United States are deftly intertwined in these books.

And speaking of books in a series, The House of Love and Death, the third book in Andrew Klavan’s superb Cameron Winter series, is due at the end of October. I wrote about the second book in the sequence, A Strange Habit of Mind, here.

When it comes to rereading fiction, I’ll be doing a lot of that, as usual. I suspect that Tracy Daugherty’s bio of Larry McMurtry, which I have just acquired, will inspire me to revisit some of McMurtry’s novels, including Cadillac Jack—one of my favorites, and often underrated, or so I think. (By the way, I love the range of a biographer whose subjects include both Larry McMurtry and Donald Barthelme!)

And for the first time—thanks to a nudge from my brother, Rick—I’m reading mysteries by a woman who wrote under the name Moray Dalton, filed under “Golden Age” British crime fiction but with a very distinctive voice. I’m grateful to those who have recovered her work from oblivion. (If you know of comparable cases, interesting writers long out of print who have been “rediscovered,” please let me know.)

That's a very good one too!

Chronicle in Stone is also good as is The Three Arched Bridge and General of The Dead Army. My favorite again is The Palace of Dreams.