The Task of the Critic

Also: A dumb argument about identity in “The Odyssey,” in praise of five Japanese novels, Jan van Kessel’s “Ark,” George Orwell on the island of Jura, and more.

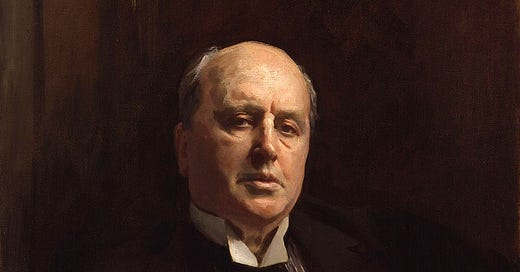

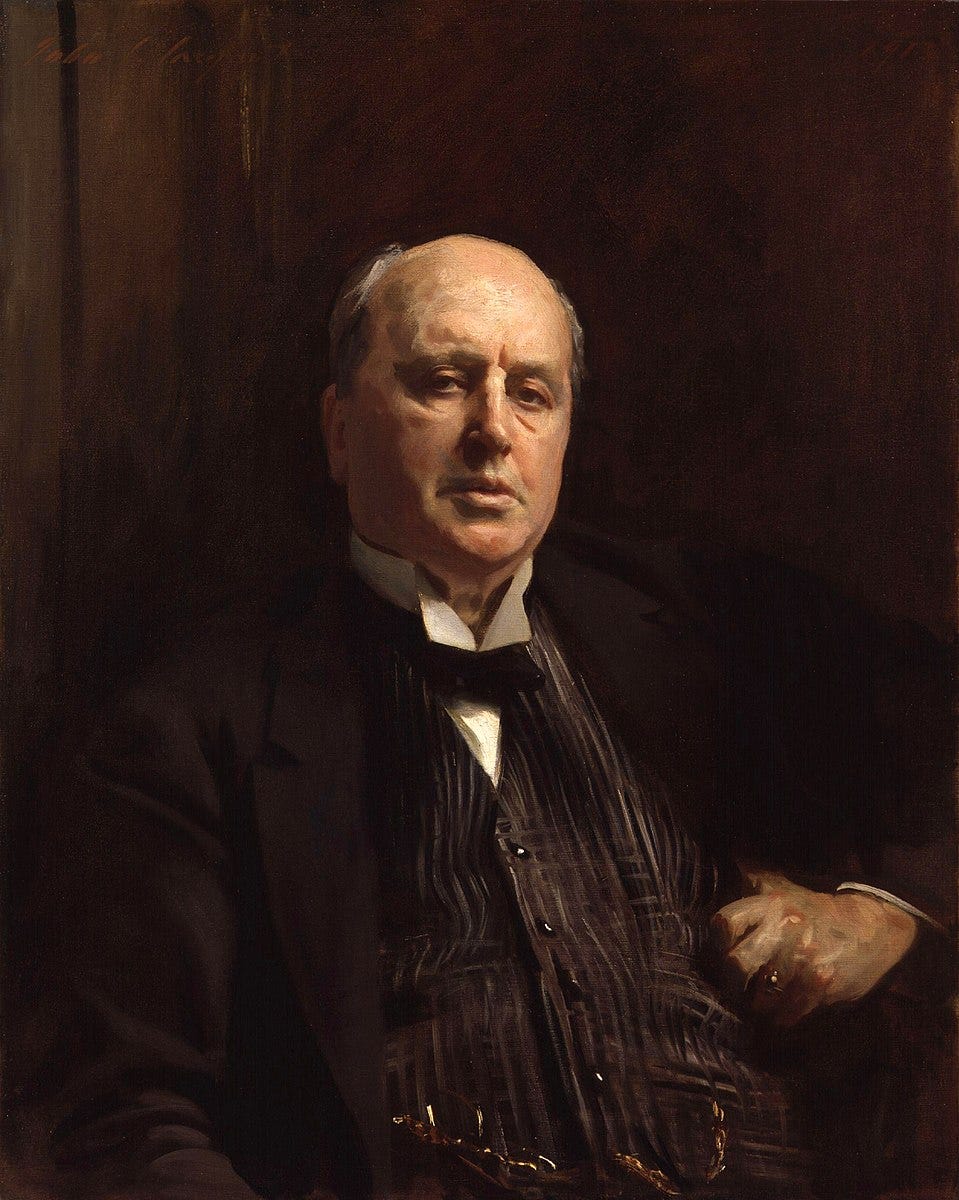

Good morning! I came across two pieces on Henry James recently that are worth sharing. First, in the latest issue of The Hudson Review, Dean Flower revisits James’ prefaces to his work:

An English novelist of his acquaintance, a woman, was congratulated for writing knowingly about the life and customs of the French Protestant youth. In fact, she knew nothing of them. But she drew on her memory of having once, in Paris, “ascended a staircase, passed an open door where, in the household of a pasteur, some of the young Protestants were seated at table round a finished meal” and glimpsed her subject. Says James, “The glimpse made a picture; it lasted only a moment, but that moment was experience.” Note the interplay of microscopic seeing and maximal absorption: “every air-borne particle” is “caught” by those spider-like webs of supple “silken threads,” exposed for only the briefest glimpse and faintest hints of life—impressionism, surely?—as the mind takes its pictures, stores them as data, and later converts them into “revelations.”

James reinforces his objections to “rules” for novice writers, particularly those based on “accident of residence or of place in the social scale,” including the standard prescription about gender: “a young lady brought up in a quiet country village should avoid descriptions of garrison life.” In a justly famous summation of the “cluster of gifts” a beginning writer needs, James formulates the sine qua non of his advice for writers, i.e., the use of untrammeled conjecture: “The power to guess the unseen from the seen, to trace the implication of things, to judge the whole piece by the pattern, the condition of feeling life, in general, so completely that you are well on your way to knowing any particular corner of it—this cluster of gifts may almost be said to constitute experience . . . it may be said that impressions are experience, just as (have we not seen it?) they are the very air we breathe.”Therefore, as James puts it finally, and most quotably, “Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost.”

I go back to these basic principles of James’s art—or at least to his favorite images for them in 1884—because I have just read a new edition of the 18 Prefaces he wrote for The New York Edition of his novels and tales. And for me, the experience of re-reading these Prefaces with their elaborate notes, has been better than good; it has been transformative. Its editor, Oliver Herford, an Oxford-trained professor and author of Henry James’s Style of Retrospect: Late Personal Writings, 1890–1915, seems to have hit upon a new way of annotating Jamesian texts—simply by paying the fullest possible attention to them.

More:

[F]or me the central “discovery” of The Prefaces, is that James knew he could only write fiction of one kind. All of it, he confessed at the start of his Preface to The Golden Bowl, which comes last, was marked by an “inveteracy” he couldn’t change, a preference for “indirect” and “oblique” methods, for “‘seeing my story,’ through the opportunity and the sensibility of some more or less detached, some not strictly involved, though thoroughly interested and intelligent, witness or reporter, some person who contributes to the case mainly a certain amount of criticism and interpretation of it.”

Note that what begins apologetically turns quickly into an apologia, spilling over with enthusiastic synonyms: “Again and again, on review, the shorter things in especial that I have gathered into this Series have ranged themselves not as my own impersonal account of the affair in hand, but as my account of somebody’s impression of it. . . . The somebody is often . . . an unnamed, unintroduced and (save by right of intrinsic wit) unwarranted participant, the impersonal author’s concrete deputy or delegate, a convenient substitute or apologist for the creative power otherwise so veiled and disembodied.”

Note that James is no longer counting on this witness or deputy—like Winterbourne or Fleda Vetch or the telegraphist in In the Cage or the governess in “The Turn of the Screw”—to be reliable, i.e., one upon whom nothing is lost.

In short, the little things are what matter in fiction. And the little things are what matter in criticism, too, Nick Ripatrazone argues in a piece at The Metropolitan Review. The critic, he writes, must “see small and think big”:

In 1905, James spoke to the Contemporary Club of Philadelphia, a literary and artistic group (Walt Whitman and Woodrow Wilson had been previous guests). His subject was the French writer Honoré de Balzac. James had been writing about Balzac for thirty years. Balzac was James’ lodestar: James had “learned from him more of the lessons of the engaging mystery of fiction than from anyone else.”

James owed much to Balzac, and his debt is revealed through the care of his engagement rather than mere deference. Balzac’s “inordinate passion for detail” is “also his great fault,” yet such saturation is “essentially prescribed by the terms of his plan.” A critic needs to see small and think big, and James was able to perceive Balzac’s narrative method as being “characteristic and constructive.” Although Balzac’s details “multiplied almost to madness,” the style revealed “the measure of his hallucination.” Balzac wished to animate “the palpable, provable world before him,” yet his singular vision meant that he “collected his experience within himself.”

James proceeds to introduce an ambitious analogy, likening Balzac to “a Benedictine monk leading his life within the four walls of his convent.” A libertine Catholic with an especial penchant for Jesuits, the image of Balzac as a coffee-fueled ascetic is a plausible one. James, though, had a gift for teasing out the complexity of his analogical thinking. Balzac embraced a hyperbolic image of himself; “he was most at ease, while he wrought, in the white gown and cowl.” Despite his monkish tendencies toward art, Balzac’s “subject of illumination was the legends not merely of the saints, but of the much more numerous uncanonized strugglers and sinners, an acquaintance with whose attributes was not all to be gathered in the place of piety itself; not even from the faintest ink of old records, the mild lips of old brothers, or the painted glass of church windows.”

Criticism, done well, is performance. Criticism done best opens the lives of writers, as well as their literature. James’ speech on Balzac (which was later revised and published as an essay) includes his central literary thesis. The novel matters as a literary and artistic form, and the best type of criticism arises from specificity and sustained engagement with “concrete instance[s] of the art” rather than abstractions. The best that a critic — and budding fiction writer could do — is to find “some great practitioner” of the craft, “some ample cloak under which we may gratefully crawl.”

James is clear: criticism matters, and criticism about the novel as an art form, ideally, should be done by practicing artists, whose own style and sensibility are forged in the furnace of technique.

It is surely a good thing for “practicing artists” to write criticism, but it is also good that non-artists to write criticism, too. It seems to me that critics like Erich Auerbach, Northrop Frye, and M.H. Abrams were able to do the sort of “big thinking” that Nick identifies because criticism was their sole focus and their perspective was uncolored by the preoccupations of their own art.

Speaking of criticism, Daniel Mendelsohn gives us an example of how not to do it in a piece about “identity” in The Odyssey for The New York Times:

If every era finds its own interest in the Odyssey, it’s the slipperiness that today’s audiences and creators recognize, steeped as we are in debates about identities political, social, gendered and sexual in a world that, like that of Odysseus, often seems darkly confusing.

The poem complicates the question of identity from the start. Its opening lines, where a poet typically announces his subject and theme, conspicuously neglect to mention Odysseus’ name, referring to him only as “a man”: “Tell me the tale of a man, Muse, who had so many roundabout ways / To wander, driven off course.” (Compare the opening of the other great Homeric epic, the “Iliad,” which tells you right up front who it’s about: “Rage — sing of the rage, Goddess, of Peleus’s son, Achilles.”) Just who is this man? Hard to tell. Later, at the beginning of one of the hero’s best-known adventures, Odysseus adopts a pseudonym, No One, when first encountering the one-eyed giant Cyclops. This is a useful fiction. (After the hero blinds the Cyclops, the creature calls out to his concerned neighbors, “No One is hurting me,” so the neighbors leave him to his fate.) And yet in another sense, the false name is eerily true: Odysseus has been gone from home and presumed dead for so long that he really is a nobody. His struggle to reclaim his identity, to become somebody again, constitutes the epic’s greatest arc.

Throughout his famous adventures, this trickster’s talent for altering his physical appearance and lying about his life story saves him. But when he returns home, that ability becomes a problem: When he is finally reunited with his wife, Penelope, she is disinclined to believe that this stranger, who only moments before appeared to be an elderly, decrepit beggar, is really the same man she bade farewell to so long ago. Although he does eventually prove himself to her (they exchange the ancient equivalent of a secret password), the unsettling question remains: How could he be the same person after two decades of life-changing experiences and suffering?

That paradox animates some of the most profound questions that this ancient work continues to pose and that haunt me more than ever, over a decade after my father’s death. Just what is identity? What is the difference between our inner and outer selves — between the I that remains constant as we make the journey from birth to death and the self we present to the world, which is so often changed by circumstances beyond our control, such as pain, trauma or even the simple process of aging? How is it that we always feel that we are ourselves even as we acknowledge that we change over time, both physically and emotionally? I’ve been teaching the Odyssey for nearly four decades, but I can’t remember a time when it has spoken as forcefully to my students as it does today, when so many are embracing fluid identities and asserting their right to self-invention.

Alas, if there is one thing that The Odyssey teaches us, it is that we do not have any “right” to “self-invention.” What we have instead are choices to fulfill our pre-determined roles or not. Will Penelope be a wise and good wife and wait for her husband to return home after twenty years, or will she give up on him? Will Telemachus learn to be a man by sublimating his feelings and instead trust his mother, the gods, and, later, his father? Sure, Odysseus disguises himself, but he never confuses these disguises with his true self—a self that is not invented but inherited: One of his most common epithets in The Odyssey is “noble son of Laertes.” The work offers a trenchant critique of self-assertion in the suitors, who disregard convention and party night and day at Odysseus’s home in pursuit of Penelope. To miss all of this and instead to read The Odyssey as some sort of celebration of “fluid identities” and “self-invention” is to read it with the narrowest of horse blinders.

Asako Serizawa praises five short Japanese novels in translation: “There is a certain privilege in looking at a group of novels-in-translation from a single country originally written and published across almost a century. What appears at first glance to be a disparate assortment of texts gathered solely by the date of their reissue in a new language reveals an unexpected coherence. That the following five short Japanese novels-in-translation are being made available to a wider audience now, in the middle of the 2020s, feels timely.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Prufrock to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.