The Real Problem with New MLK Statue

Also: In praise of plastic, a history of London’s fishmongers, and more.

Editor’s note: Prufrock will now be published every Monday and Wednesday. Thanks for reading.

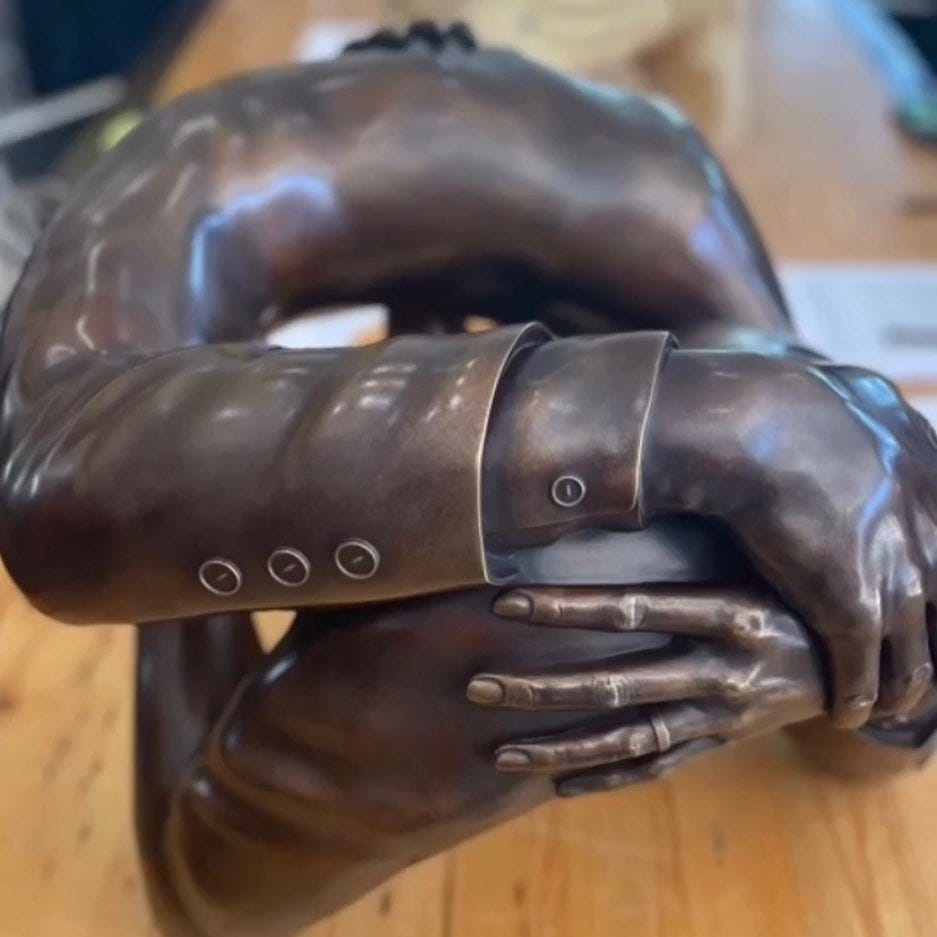

You have most likely seen the new MLK statue in Boston based on a photo of King hugging his wife, Coretta, after he learned he had won the Nobel Peace Prize. The statue was commissioned by Embrace Boston, formerly known as King Boston, which is a project of the billion-dollar non-profit Boston Foundation.

People mocked the decision of the artist to exclude the heads of both King and his wife from the statue. It does look grotesque from certain angles. In Compact, Seneca Scott, a cousin of Coretta Scott King, calls the statue “a masturbatory metal homage to my legendary family members.”

But the statue does what many have been doing to King for years, which is to make him into an ambiguous symbol of love and acceptance so that his name and legacy might be more readily used to support a variety of projects, which all invariably involve fund-raising.

The statue looks like a heart from one angle, which is also the logo for Embrace Boston, and the non-profit subsidiary clearly hopes to capitalize on it. They have a large team—three co-founders and an executive staff of 10—and have launched programs with nebulous names like The Boston Coalition and The Forward Fund that have broad goals in need of an indefinite amount of cash to support. Feel-good quotations from King and John Lewis are sprinkled across the website in order to make donors feel like they are part of something “historic.”

The goal of Embrace Boston is to “dismantle” structural racism by the year 2030—the 400th anniversary of Boston—but I bet that won’t mark the end of the organization. As Barton Swaim pointed out in a piece in Commentary a few months ago, as a “nonprofit grows and becomes an institution itself, with staff, traditions, a building, a brand, a base of supporters” it begins to exist “for its own sake, separate from its original goals. Eventually it becomes easier for the nonprofit to create fictional problems and fake accomplishments in a perpetual effort to keep the money flowing.”

Embrace Boston has a $10-million logo that has the polish of MLK’s reputation attached to it without the limits of his name (or his head). The Boston Foundation has assets in excess of $1 billion, but as with all large non-profits, it is always in need of money, and creating smaller entities like Embrace, which seem to have a definite goal, is the best way to bring in cash.

All this say, the real problem with the MLK statue is not that it’s yet another example of bad contemporary art. The real problem is that it’s a marketing campaign.

In other news, Dominic Green reviews Prince Harry’s Spare: “This is not Prince Harry's autobiography. It is a biography of a character called ‘Prince Harry,’ assembled from conversations with the real Harry by a ghostwriter, J.R. Moehringer. It is to autobiography as one of those Philip Roth novels where the main character is called ‘Philip Roth’ are to fiction, only less tedious. It is fascinating in its way, though not in the way the real Harry intends. It is a collaboration between two unequal partners, one an accomplished ventriloquist, the other believing that he has finally found his voice. Harry recorded the audiobook, so he knows exactly what is in Spare. He wants us to know that animals give him spirit messages from the beyond.”

Ronald Blythe has died. He was 100: “In the summer of 1967, Ronald Blythe cycled from his home in the Suffolk hamlet of Debach to the neighbouring village of Charlsfield. There he listened to the voices of blacksmiths, gravediggers, nurses, horsemen and pig farmers. He gave them names from gravestones and placed them in a fictional village. Akenfield, a portrait of a rural life rapidly disappearing from view, was immediately acclaimed as a classic when it was published in 1969. Never out of print and read and studied around the world, Akenfield made Blythe famous and perhaps overshadowed the many other fruits of his long years of writing – short stories, poems, histories, novels and, in later life, luminous essays and a superb weekly diary that the Church Times published for 25 years until 2017. Blythe, who has died aged 100, is regarded by his peers and many readers as the finest contemporary writer on the English countryside.”

Has academia ruined literary criticism? Merve Emre reviews John Guillory’s “erudite” and “biting” Professing Criticism: “The book’s chapters take us on a strange journey, across a landscape haunted by ghosts: the bygone disciplines of philology, rhetoric, and belles-lettres; the half-glimpsed figures of the New Critics and the New York intellectuals; strident culture warriors past and present. Guillory chronicles it all with a certain Olympian detachment, a special acuity of vision that brings history into focus with painful clarity. Professionalization, he argues, secured intellectual autonomy for criticism’s practitioners. They could produce knowledge about literature in a manner intelligible chiefly to others producing the same kind of knowledge—a project that became both increasingly specialized and increasingly justified by political concerns, such as race, gender, equality, and the environment. ‘This is a world in which some of us can specialize in the study of cultural artifacts, and within this category to specialize in literary artifacts, and within literature to specialize in English, and within English to specialize in Romanticism, and within this period to specialize in ecocriticism of Romantic poetry,’ Guillory writes. The cost of this professional autonomy is influence. ‘How far beyond the classroom, or beyond the professional society of the teachers and scholars, does this effort reach?’ he asks, knowing that the answer is: not far at all.”

In praise of plastic: “It is hard to imagine modern civilization without plastic, which is so derided. The most widespread luxury belief of all is that plastic is bad and that you can be morally better by not using plastic bags and forks. Plastic is the sort of foundational material that has made life immeasurably better, safer and more tolerable in the last hundred years or so. We should celebrate it more.”

A history of London’s fishmongers: “These street sellers occupied a unique place in society. Though their work was unregulated and usually poorly remunerated, they nevertheless drove London’s social and economic change. Tavener writes: ‘Hawkers help us reconstruct London’s story around the basics of metropolitan life: inter-actions on the street, the exchange of essentials and the struggle with material conditions, much of which took place outside formal institutions and fixed sites and beyond the grasp of governors and magistrates.’ Comprehensive regulation came later with pitch-assigned covered markets, and ultimately the advent of supermarkets. But for 300 years this ‘informal retail’ was the principal provider of fresh produce to neighbourhoods not served by wholesale markets.”

A life of Buster Keaton: “I knew Buster Keaton. I carried his ukulele to Grand Central Station, where he and my father, Bert Lahr, were boarding a train to Toronto to make a film called Ten Girls Ago. It was 1962; I was 21, old enough to know I was walking with two comedy legends. In my mind’s eye, I can still see the platform and the waiting silver carriage. I remember my surprise at Keaton’s gravelly voice and the swank black cigarette holder that seemed out of place in his rumpled forlorn face. There was mischief in their banter. These old vaudevillians were back on the road again, comrades in comic arms, doing what they had done from the beginning of their long peripatetic careers, surviving by their wits.”

Theodore Dalrymple remembers Paul Johnson, who died last week. He was 94: “His stream of books was almost torrential. Perhaps his biggest and most influential one was Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Eighties (1983). A believing Catholic, Johnson saw the horrors of the century largely as a consequence of the decline of religious belief.”

The two worlds of George Frost Kennan: “George Frost Kennan’s status as a major figure in world history comes from his role in crafting postwar foreign policy, making him a sort of founding father of the American century. A diplomat whose famous ‘long telegram’ of 1946 and subsequent ‘X article’ for Foreign Affairs magazine in 1947 erected the intellectual scaffolding for the so-called “containment” doctrine, he spent half of his life repudiating his greatest achievement. He despaired that he had been misunderstood — that the Cold War need not have been as militarized as it had been. He was haunted by the all-too-real prospect of nuclear Armageddon and was a powerful advocate for a policy of ‘disengagement,’ wherein both the Soviet Union and the United States would pull back their troops from Europe, leaving it a neutral space rather than a divided field of contestation. He memorably testified against the Vietnam War before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1966, an establishment Cold Warrior arguing that the misapplication of containment was yielding senseless slaughter in Indochina. And he was an early environmentalist, worried that a mindless devotion to technological progress was irreparably damaging not just nature itself but mankind’s ability to relate to the world meaningfully.”

Paul Johnson’s art history survey was the first place I heard of fashion art, and he applied it not just to post-modernism but to early variants such as art nouveau. It was the first time I understood that our discontents are have deep roots.