The Poetry of Ernest Hilbert

Also: The misogyny myth, Joe Biden’s book sales, misreading Tolkien, what it’s like to be a BBC singer, and more.

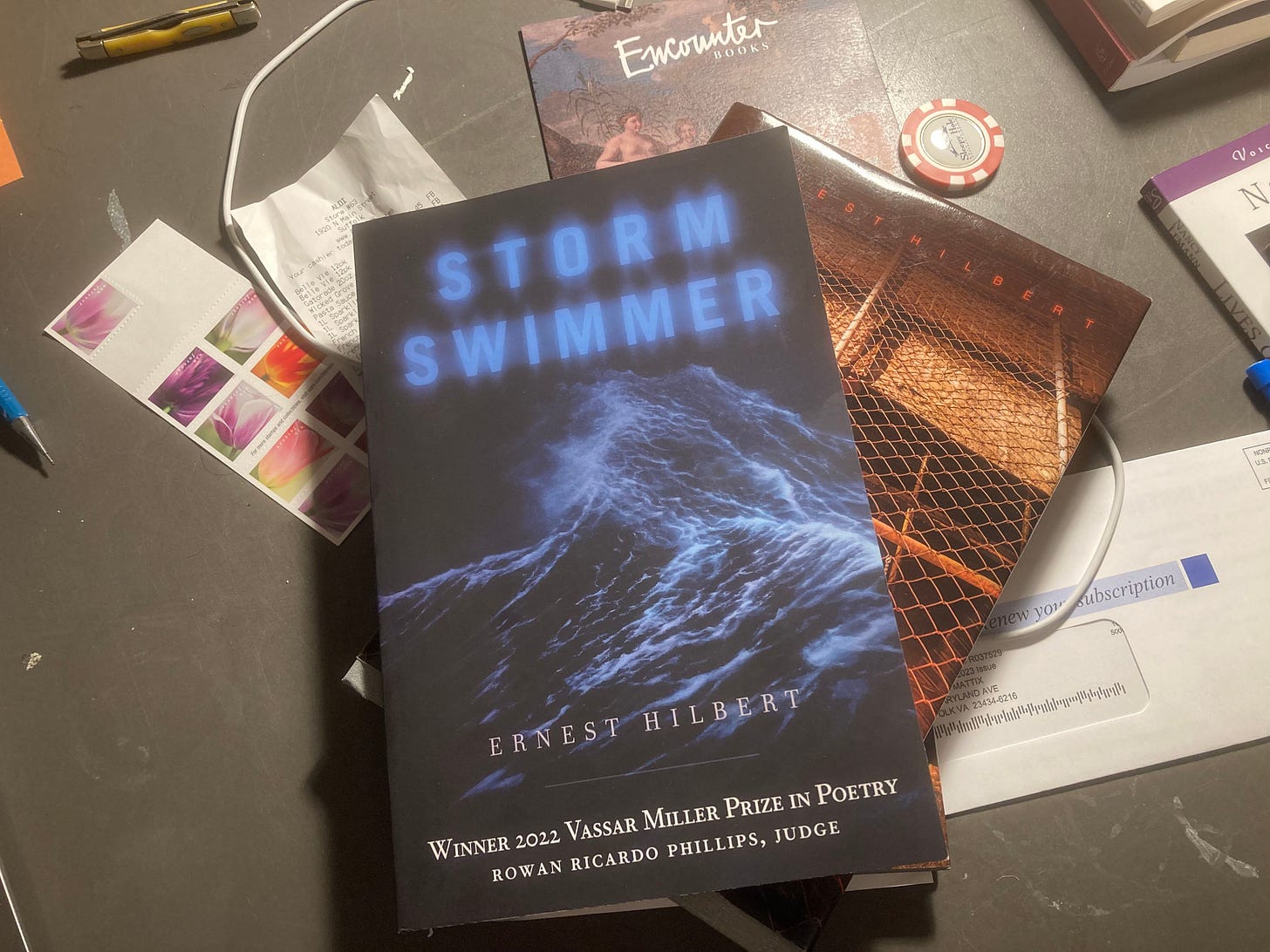

I recently finished Ernest Hilbert’s most recent collection of poetry, Storm Swimmer. It was a pleasure.

In a review of Hilbert’s first book of poems, Sixty Sonnets, Adam Kirsch compared him to Robert Lowell: “In these sonnets, whose dark harmonies and omnivorous intellect remind the reader of Robert Lowell’s, Hilbert is alternately fugitive and connoisseur, hard drinker and high thinker.”

That’s mostly right. In his work, Hilbert writes about New Jersey summers on trashy beaches, attending Monster-Mania Con with his brother, attending Easter services, his dead cat, and drinking absinthe in New Orleans. His references are classical and contemporary. The world is beautiful and junky; our lives are marked by completely unexpected moments of happiness and regular bouts of boredom, depression, and self-destruction.

Hilbert has said that his third book Caligulan is about “the modern sense of anxiety and helplessness that is like death by a thousands cuts.” My favorite poem from Caligulan in this tenor is probably “Funeral Insurance” about two people who have grown old and distant. They live alone in a small house that no one visits:

We do not rhyme much anymore,

Yet here we are—a pair.

We hardly ever get to the store,

And find it hard to care.

We’re fixed here in our tiny home,

The stair-chair stuck half way,

The blinds cocked, sofa seeping foam,

Neighbors long moved away.

At times, we can’t stand each other,

Too slow, too uncertain to run

Off or start with another,

So, together, we’re done.

It’s years since we were really young,

But now we’re really old,

Ancient as our house, which sits unsold,

Doorbell and phone unrung.

Me, cold and unrecorded as snow

That fell at sea, and you,

A flight, first listed overdue,

Then lost, long, long, ago.

We have poems in the same vein in Storm Swimmer, like “Martini Shot,” about an aging and struggling adult film actress:

She hasn’t slept for days, and it shows.

She’s two payments behind on the pink ‘Vette

Parked out front in the heat. The hot

Tungsten is fierce over each tuck

And fold, her butterfly tattoo faded to flaky blue.

After a “performance,” Hilbert writes, she thinks:

She’d like own a ranch on a snow-lathered hill

Or a villa where gulls scream and waves spill

Around black slivers of rock. The thought scatters

Like the end of a day that feels like all the others.

“The world,” Hilbert writes, “shrinks.”

One of the things I appreciate about Hilbert is the understated realism of his work. He tries to capture—without theatrics or moralizing—what it feels like to live in the contemporary world. In fact, realism is a kind of ethic for him. His work is, in many ways, about facing the suffering and cruelty of life with honesty and courage.

Hilbert is a life-long swimmer, and swimming in the ocean in particular is a symbol for this honest and courage. He told Tim Green recently on the Rattlecast podcast that swimming in the ocean in particular reminds you that:

You’re in an element that is much more powerful than you are and vastly larger and more ancient, and you can control yourself up to a point, using discipline, exertion, a struggle for survival, or you may do it for joy and happiness, whatever reason, but you still are only able to control yourself within the whims of this larger thing . . .

We see this tension in “Pelagic,” which is a sort of title poem for Storm Swimmer. Hilbert writes:

I face an ocean, its lurid rush and pull

The same as ever, though I have aged.

I step in—small cool splashes on my calves—

Then shoulder through hard linebacker waves.

He swims out until the breakers “hide the beach from me” and imagines “I’m in a world only / Ocean and sky, four billion years ago”:

Or in a time to come, floating without

The earth to save me, as long as I might.

It’s a lovely final couplet that, for me, especially with that sly off rhyme, is pure Hilbert.

In other news, no one buys book about Joe Biden, Daniel Lippman reports in Politico: “NBC News’ Jonathan Allen went on a multi-stop national tour when he co-wrote a book on how Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump during the 2016 campaign. Shattered: Inside Hillary Clinton’s Doomed Campaign, written with fellow journalist Amie Parnes, sold more than 125,000 copies and landed on the New York Times best-seller list. But for the pandemic-era book he and Parnes wrote on Joe Biden, Allen didn’t even get the satisfaction of seeing a copy in stores. He didn’t go on a tour, either. Lucky: How Joe Biden Barely Won the Presidency never made the Times best-seller list and so far has sold fewer than 10,000 copies since its release in March 2021.”

Were women locked in “dimly lit inquisitorial chambers” in the Middle Ages and subjected to a barrage of questions and threats from male inquisitors? No:

Men were routinely taken to the inquisitorial chamber – in this case a room designated and equipped for hearing and recording interrogations in the Dominican convent of Sant’Eustorgio: of the 29 men interrogated in this trial 18 were questioned here. Five were taken to the inquisitor’s personal living quarters in the same convent. Occasionally they were interrogated elsewhere: one at the gates of the convent and three at other ‘houses of the inquisition,’ sometimes at a different monastery or elsewhere in Milan. The 38 women, meanwhile, were always handled at the boundaries of or outside the actual cloister of Sant’Eustorgio: one was interrogated at the gates of the convent, nine in other religious houses and the majority (28 cases) in a church, usually that of Sant’Eustorgio itself. By contrast, no man was interrogated in a church. The pattern is clear.

Historian Jill Moore has found a similar pattern in Bologna: women were handled in churches, or even in their own homes, rather than in the inquisitors’ cloister, ‘presumably to avoid exposing other friars to contact with their polluting presence.’ Such reasoning would certainly have been familiar among religious men who had all taken a vow of chastity. The Rule of St Augustine, under which the Dominicans professed, was very concerned about the potential for mere eye contact with women to corrupt monks.

The solution to this was written into an early Dominican statute, which declared that women ‘shall remain in the church reserved for the laity or outside in a fixed place, where the prior can speak to them about God and spiritual matters.’

The misogyny myth: In a long essay in City Journal, John Tierney looks at new research that shows that misogyny is not “rampant in modern society.” In fact, it hardly exists at all. What is not only tolerated, but “actively encouraged,” however, is misandry:

For decades, researchers have hunted for evidence of overt discrimination against women as well as subtler varieties, like “systemic sexism” or “implicit bias.” But instead of detecting misogyny, they keep spotting something else.

Consider a new study that is one of the most sophisticated efforts to analyze implicit bias. Previous researchers typically looked for it by measuring split-second reactions to photos of faces: how long it takes to associate each face with a positive or negative attribute. Some studies reported that whites are quicker to associate black faces with negative attributes, but those experiments often involved small samples of college students. For this study, a team of psychologists led by Paul Connor of Columbia University recruited a nationally representative sample of adults and showed them more than just faces. The participants saw full-body photos of men and women of different races and ages, dressed in outfits ranging from well-tailored suits and blazers to scruffy hoodies, T-shirts, and tank tops.

Who was biased against whom? The researchers found no consistent patterns by race or by age. The participants were quicker to associate negative attributes with people in scruffier clothes, but that bias was fairly small. Only one strong and consistent bias emerged. Participants in every category—men and women of all races, ages, and social classes—were quicker to associate positive attributes with women and negative attributes with men.

Ted Gioia lists ten things he likes about Joan Didion and her writing: “In both her fiction and non-fiction, she taught me ways of perceiving my own milieu on the West Coast that I’d have never learned on my own.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Prufrock to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.