"The Great Gatsby" at 100

Also: First Things’s Second Annual Poetry Prize, a biography of Erik Satie, a history of spelling, remembering Mario Vargas Llosa, and more.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby was published 100 years ago this month. Raquel Laneri writes about the men who may have been models for Fitzgerald’s most famous character:

“There seems to be an endless fascination with discovering who the real Jay Gatsby might have been, almost as if Fitzgerald were incapable of imagining such a man,” said James West, a retired English professor at Penn State University and the author of several books on Fitzgerald. He noted that there are multiple suspects.

Herbert Bayard Swope was a newspaper man who threw lavish parties at his mansion in Great Neck, that Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, attended. Joseph G. Robin, a Russian-born immigrant to the US, changed his name, made a fortune in banking, and held fancy “automobile parties” on Long Island before going to prison for bribery and embezzlement. Last year, journalist Mickey Rathbun published a book about her grandfather, George Gordon Moore, claiming he was “the real Gatsby.”

George Monaghan considers Gatsby’s “pastlessness” in The Metropolitan Review: “Very wrong was the novelist who told Fitzgerald that “to make Gatsby really great, you ought to have given us his early career.” Gatsby needs, at first, to be pastless. Fitzgerald wrote and then deliberately excised the story of Gatsby’s early days — it was later released, with different names, as the short story “Absolution.” Fitzgerald instead dazzles us with the early swirl of fantastic rumors about Gatsby’s past in order to convey its unknowability. When we first see him on the dock, we know nothing of him, and he might be aspiring to anything. The scene vibrates with possibility . . . Totally free self-creation demands emancipation from the past.”

In The Nation, Mark Chiusano writes about Fitzgerald’s edits:

Among the centennial arrivals is a Library of America annotated edition, with side-margin commentary by the venerable Fitzgerald scholar James L.W. West III. Surely Fitzgerald would have been thrilled with this compendium—a victory after all his end-of-life worrying. This new edition does, in fact, have a preface not by him—plus an introduction from an admirer, just like he wanted—as well as 13 short letters between author and editor, many illustrations and photographs, and the kinds of gem-like notations that are certain to make lovers of Fitzgerald arcana happy and should enhance the experience of someone even on their third or fourth reread. I was struck, for example, by the minor-seeming editorial quibble that Daisy and Tom Buchanan’s little daughter is described as 3 years old, when in fact she should be 2, according to other dates in the novel. It turns out that Fitzgerald had originally set the narrative in 1923 and later shifted it to 1922—the year in which both Ulysses and The Waste Land were published, and the year that Fitzgerald highlighted in his essay about the Jazz Age, a term he coined. He forgot to change the daughter’s age, however—a mistake that matches the funny way children are obscured or mostly absent in this book, ghostly figures connoting a future that the main characters, in the flush of constant selfish-reflection, rarely bring themselves to consider. Daisy and Tom, despite all their partying and philandering, are parents, mind you. I’ve always loved how Daisy briefly shows off her “bles-sed pre-cious” daughter to Nick Carraway and a stunned Jay Gatsby, before ushering the girl back to her governess while Tom crashes through the door with gin rickeys.

Mostly, Fitzgerald’s edits were improvements, not intriguing errors. All that revision comes out loud and clear in this edition, which is a real lesson for those among us who think that everything has to be perfect on the first go. The finicky author took his editor’s suggestions to space out the revelations about Gatsby’s origins and ended up doing a “thorough revision of the galley proofs,” West writes, including handwritten changes (some of which are included), freshly typed new passages, some pages with a mixture of both, dialogue sharpened everywhere, and lots moved around. West notes somewhat approvingly that the hard workers of the Scribner’s production team transferred all those revisions on time, resulting in an edition that, “apart from a few typos, was free of significant error.”

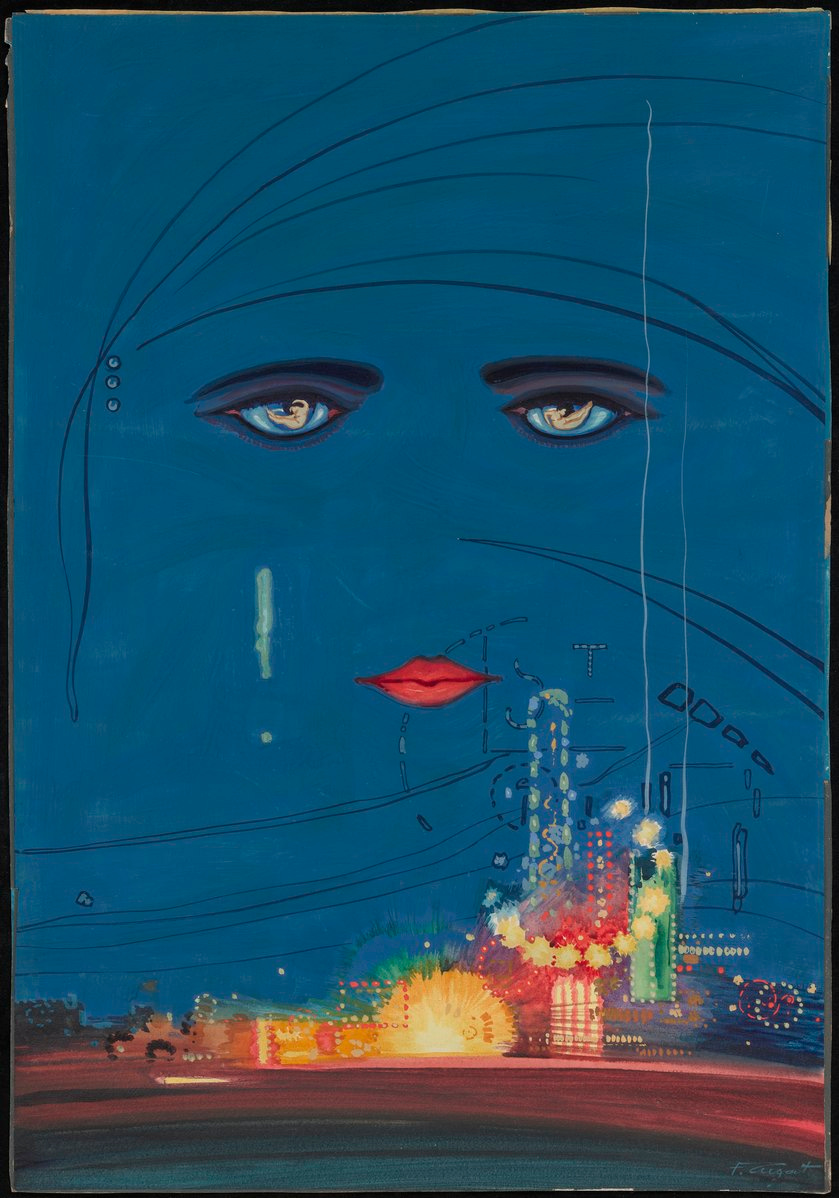

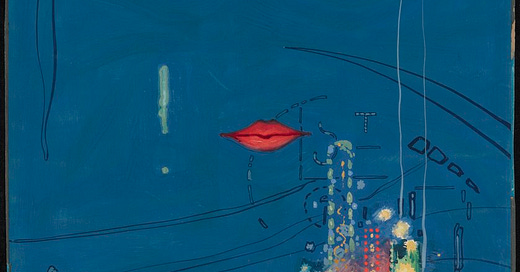

Here we see just one example of how tactile the world was when Fitzgerald wrote his masterpiece. He’s making eternal magic in longhand on big sheets of paper, practically moments before the printing press has to run. That includes some of the key symbols of the book—for example, the green light Gatsby sees at the end of Daisy’s dock started out as a “glimmer.” As for the now-revered cover—with its haunting image of a face floating over a dark blue amusement-park scene—that came about through happenstance: Fitzgerald saw the painting, or a sketch it was based on, in his publisher’s office before he departed for France. The artwork was not tied to any particular book yet, but Fitzgerald loved it.

And Fitzgerald’s granddaughter makes connections between the novel and the Fitzgeralds’ family life: “My mother, Scott and Zelda’s only child, appears early in the story. When Daisy gives birth she says, ‘I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.’ This is uncannily similar to what Zelda said in 1921 as she emerged from the ether of childbirth. ‘Isn’t she smart—she has the hiccups. I hope it’s beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool.’ Of course, my mother was no fool. She was christened Frances Scott Fitzgerald, and called Scottie . . . Scott was a devoted and difficult father. He was virtually a single parent when my mother was a teenager. He tried to dictate what she read. He tried to supervise her manners, her interests, and her friends. Scottie wrote, ‘My father had a terrific sense of wasting his own life, his youth, and he was trying to prevent me from squandering my resources as he felt he had squandered his.’”

In other news, submissions are now open for First Things’s Second Annual Poetry Prize. Dana Gioia will be this year’s judge. Entrants may submit up to two poems. All judging is blind.

There is no fee to submit work, which is increasingly rare for such prizes because of the work they require to judge. Last year we received over 1,000 submissions. The two winners were Josiah Cox for “Two Owls” and Ryan Wilson for “Gather Ye”—out of about 20 finalists that were also very accomplished. It was a hard prize to judge, which is what you hope for with such things. The deadline is June 30th.

Alexander Larman reviews the new season of Black Mirror: “Charlie Brooker’s cautionary technological tales have now been running for well over a decade, and they are almost in danger of seeming old-fashioned. When Black Mirror began in 2011, Instagram was only a few months old, the iPhone was a new novelty just coming into the mainstream, and Elon Musk was best known for being CEO of Tesla. Now, virtually everything in the world has changed, and Big Tech plays roles in our lives that the ever-cynical Brooker could barely have imagined. There is, naturally, a residual irony that in order to afford the budgets – and starry casts – that the show continues to demand, it long since left its original home on Britain’s Channel 4 for the deeper-pocketed Netflix, which still funds it into its seventh series. The good news is that Black Mirror, which had been in danger of turning into self-parody, has taken the various technological advances and changes that are now the topic of daily discourse, most notably the apparently inexorable rise of AI, and has bolted them onto some of the show’s best, old-fashioned storytelling.”

John Banville reviews a new biography of Erik Satie: “If [Ian] Penman’s cheery chappiness can at times seem studied, he is for the most part admirably accommodating and affirmative, and always enthusiastic. He has little time for the grand Germanic musical statements of the 19th century, which Erik Satie and Debussy gigglingly referred to as Sauerkraut. Satie is an ideal subject for him, and Three Piece Suite is, as you would expect, a glorious celebration of this most elusive and ambiguous of early 20th-century composers.”

Barbara Spindel reviews a new book about spelling:

Long before Noah Webster completed his 1828 magnum opus, “An American Dictionary of the English Language,” he published a wildly successful primer called “A Grammatical Institute of the English Language”—widely known as the “Blue-Backed Speller”—which sold close to 25 million copies in his lifetime. The spelling primer’s first edition conformed to traditional English orthography, with, for instance, entries for “theatre,” “publick” and “colour.”

After the publication of the “Blue-Backed Speller” in 1783, however, Webster became increasingly committed to an American dialect that would be distinct from British English. His dictionary had an explicitly patriotic agenda: to unite the language of the regionally diverse United States and to declare its independence from the former motherland. In addition to such Americanisms as “moccasin” and “cookies,” Webster featured updated spellings of a number of words, including “theater,” “public” and “color.”

As Gabe Henry notes in “Enough Is Enuf,” a history of the largely futile efforts to overhaul English spelling, Webster wasn’t motivated by nationalism alone. He had also become an adherent of wholesale changes to written English, lamenting its “irregular” orthography. “If a gradual reform should not be made in our language,” the lexicographer warned in 1790, “it wil proov that we are less under the influence of reezon than our ancestors.” A quick glance at that sentence is sufficient to grasp that not all of Webster’s hoped-for modifications caught on.

Terry Eagleton writes about the rise and fall of Standard English in UnHerd:

Standard English itself grew out of a regional dialect, roughly the area containing the key centres of London, Oxford and Cambridge. It was part of a strikingly successful attempt by a rising middle class to consolidate its cultural power. Just as they needed a common currency, so they needed a shared way of speaking by which they could recognise each another instantly, without going to the trouble of inventing a secret handshake or wearing a old school tie. “A pat on the back” now sounded like “a pet on the beck”, while “barth”, which was once amusingly rustic, was now polite usage for “bath”. “Really” came to sound like “rarely”, though the two can almost be opposites (as in “I really/rarely enjoy dancing”), and in Sloanish circles “It’s my birthday” became hard to distinguish from “It’s my bathday”, suggesting that you took a bath only once a year.

There are also variations in volume. Generally speaking, people get louder as you travel from Brighton to Lancaster, and there’s a myth in Northern Ireland that Protestants speak louder than Catholics. Some of the public school boys I encountered as a student at Cambridge in the early Sixties seemed to bray rather than speak. This was because only oiks like myself were anxious about other people overhearing their conversation, whereas those with true social authority didn’t give a toss. I was once sitting in a Cambridge hairdresser’s along with a dozen or so other customers when a large young man in cravat, hacking jacket and knee-high boots put his head round the door and bellowed to the barber “Johnnies, Albert!” (“Johnnies” meant condoms in those days.) It’s true that barber’s shops were one of the few places where you could buy such goods in those sexually repressed times, but the transaction was usually hushed and furtive, like buying hard drugs today. There was nothing hushed and furtive about the Right Honourables who swaggered along King’s Parade and hooted in cinemas at the feeblest joke.

Pope Francis advances sainthood cause of the architect of Sagrada Familia: “The Vatican announced that the pope authorized the decrees during an audience at the Vatican April 14 with Cardinal Marcello Semeraro, prefect of the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints . . . The pope . . . recognized the heroic virtues of Antoni Gaudí, a Spanish architect and designer who was born in Catalonia in 1852. Gaudí, who created many one-of-a-kind projects, eventually renounced secular art and dedicated more than 40 years of his life to building Barcelona’s Basilica of the Holy Family, often referred to by its Spanish name as the Sagrada Familia.”

Mario Vargas Llosa has died. He was 89: “Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, one of the pivotal figures who ignited a global boom in Latin American literature, has died aged 89. His death on Sunday was announced in a statement signed by his children, Álvaro, Gonzalo and Morgana Vargas Llosa. Vargos Llosa ‘passed away peacefully in Lima … surrounded by his family,’ they wrote . . . Over a career that spanned more than 50 years, Vargas Llosa charted power and corruption in a series of novels including The Time of the Hero, Conversation in the Cathedral and The Feast of the Goat. Living a life that was as colourful as his fiction, Vargas Llosa also launched a failed bid for the Peruvian presidency, nursed a long-running feud with Gabriel García Márquez and triumphed as a Nobel laureate in 2010.”

I read Llosa Vargas’ “The Storyteller” when it was first published in English. I really enjoyed the clever and challenging puzzle in the alternating chapters. I recommended it to my sister who, without reading it, chose it for her turn’s suggestion to her book club. She said she was practically thrown out of the club because no one could finish it.

Probably why I’ve never joined a book club.

I’m part of that minuscule group who think that The Great Gatsby is absurdly overrated.I think its beautifully written, poorly plotted ( the mistress of Tom Buchanan gets run over in a Queens gas station by Daisy and then the husband kills Gatsby- pure Days of our Lives melodrama) and really rather inconsequential.

Mario Vargas Llosa was a novelist I really valued. Conversation in the Cathedral is a novel that I’ve come to realize is a great novel. I’m also partial to Death in Andes.