That Patricia Lockwood Essay on David Foster Wallace

Also: Shakespeare as woman, political myths, 119-year-old library book, and more.

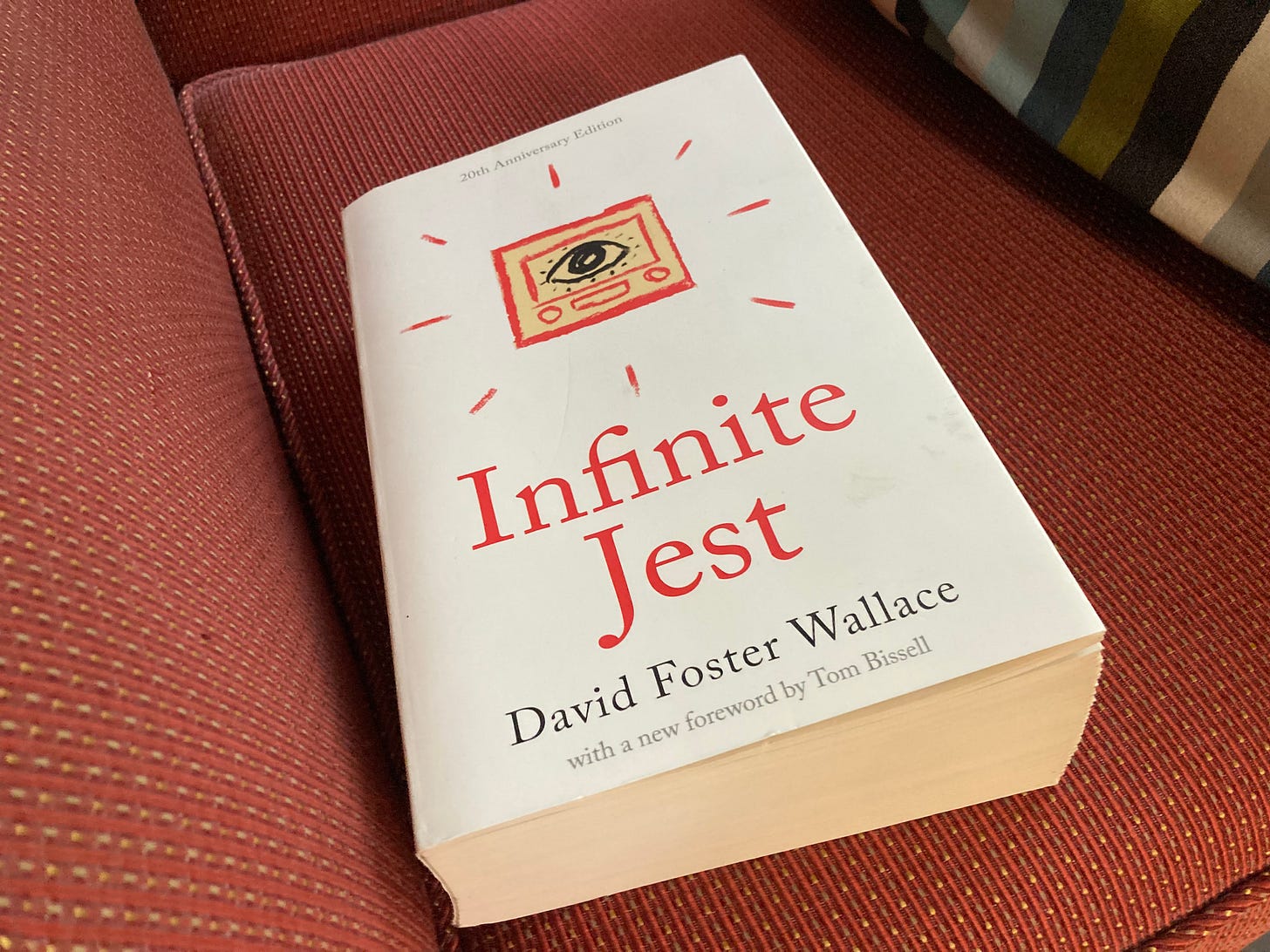

In the latest issue of London Review of Books, Patricia Lockwood uses David Foster Wallace’s posthumous novella, Something to Do with Paying Attention, which was part of his draft of The Pale King, to write a long essay—it’s 8,121 words—taking stock of David Foster Wallace. Some people on Twitter loved it. Others did not.

I don’t really care for David Foster Wallace’s fiction, but whatever one thinks of Lockwood’s essay, it does strike me as very much du jour.

First, a confession: Some people find Lockwood funny, but to me her zingers come off as too rehearsed. They are the sort of things that would be great in a conversation late at night but sound too performative—too reported—in the text:

Infinite Jest – man, I don’t know. Perhaps I would have enjoyed it more had the rhetorical move not so often been ‘and then this little kid had a claw.’ It’s like watching someone undergo the latest possible puberty. It genuinely reads like he has not had sex. You feel not only that he shouldn’t be allowed to take drugs, but that he shouldn’t be allowed to drink Diet Pepsi.

What were the noughties? A time when everyone went to see the Blue Man Group for a while. Men read David Foster Wallace. Men also put hot sauce on their balls.

I have always appreciated Wallace most in his monologues and I can, like my father, hear confessions all day; Hideous Men ought to be my book. Instead, I found myself generally standing opposite to Smith’s assessments: I think ‘Forever Overhead’ is juvenilia, I find ‘Church Not Made with Hands’ to be rank fraud, and I would like to put ‘Octet’ in my ass and turn it into a diamond.

The truth about Brief Interviews is this: it only gets good when we’re about to be raped.

I know other people loves these, and maybe I’m wrong to read them the way I do, but that’s my opinion right now.

What isn’t a question of taste, at least I don’t think it is, is that we get very little aesthetic engagement in this piece and in many of Lockwood’s essays. She gets close sometimes. She drops the occasional moralist-aesthetic remark like:

The thing about the ‘I remember’ model is it’s inexhaustible, it can just go on. Recollection engenders recollection. Test it.

Or:

A whole novel could take flesh from that fact, one about the idea of bureaucratic identity as opposed to individual identity: memories, mothers, sideburn phases, the way we see ourselves. That we are, at our core, a person; in the bed of our family, a name; and out in the world, a number. Of course, as so often with Wallace, on actual investigation this turns out not to be true. The fact withdraws itself, and only the epiphany remains.

Or:

I was sceptical of Sarah McNally’s claim, in her brief and somewhat subdued introduction to Something to Do with Paying Attention, that it is ‘not just a complete story, but the best complete example we have of Wallace’s late style’, but that’s exactly what I found it to be.

Or:

Every so often Wallace offers you a set piece that’s as fully articulated as a Body Worlds exhibit – laminated muscles pinwheeling through the air, beads of plasticine sweat flying – or pauses the action to deliver a weather bulletin that approaches the sublime. The rest is Don DeLillo played at chipmunk speed.

And:

I would recommend that you read The Pale King in its entirety – it says something about how novels work, and how they don’t work, and how, if you are avoiding life, it is easier sometimes to exist in the very long middle of them.

This makes the piece feel like criticism, but it’s not. She tells us that The Pale King shows us “how novels work, and how they don’t work,” but leaves us to figure out exactly what this means.

In the end, her stylistic remarks are performative, which is perhaps how she views criticism. It is an occasion for the critic to create a text of her own. This has been with us since at least Edward Said’s 1983 remark that a work of criticism is not “secondary” to the work of literature. Criticism, he continues, “no less than any text, is the present in the course of its articulation” (emphasis mine).

I don’t have a problem with this sort of writing per se. It can be fun, which is what a lot of people think Lockwood’s writing is, but it’s not criticism, and in the end, it either works or doesn’t to the degree that you find the critical persona interesting, funny, touching, or whatever. (Or, in other cases, to the degree that you find the political idea that the text supposedly illustrates true.) The essay doesn’t depend—or only secondarily—on the “rightness” of the critical remarks vis-à-vis the text as text.

This is, of course, why Lockwood, and so many other contemporary critics, rely so heavily on personal anecdote. Normally these would seem out of place in a work of criticism, in a discussion of a writer’s style, but they work here because, well, this isn’t a review or a critique exactly, it’s a Lockwoodian performance, so she can write about waiting in her mother’s van outside an IRS office, allude to her father’s Catholicism, imagine rereading Wallace without knowing about his bad actions, and so forth.

The piece teases us with the popular question of the day: Should we even read David Foster Wallace since he was a bad man? Lockwood, thankfully, doesn’t say no, but her own literary question, to the degree she has one, is also largely a biographical one: Why did David Foster Wallace write a long book like Infinite Jest? Her answer: He did it because of the therapeutic benefits of being completely absorbed by something else:

Why did he turn to it? Because it was impossible, probably – just as Infinite Jest had been to him fifteen years earlier. And when he took on the impossible book, something sometimes happened to him: a run, a state of flow, a pure streak . . . ‘Derivative Sport’ ends famously with a day on the court, hitting balls with Gil Antitoi. ‘A kind of fugue-state opens up inside you where your concentration telescopes toward a still point and you lose awareness of your limbs and the soft shush of your shoe’s slide.’ His life in tennis was spent chasing this moment, he tells us; he has been talking about fiction, too, this whole time.

And:

Something to Do with Paying Attention has the spirit of his best non-fiction, that of the set-apart morning, with a ray shining on the page. It both demonstrates his greatest gift and represents the desire to have this part of him set alone from the rest.

Stylistic questions are, for her, questions of psychology. This is why reading for her is also primarily a therapeutic experience rather than an aesthetic one. She concludes with this:

There is a great deal of handwringing about whether we can still enjoy the work of hideous men. The question is not typically how to root out influence. It is whether we can still enjoy, but we are reaching for another word beyond it. What we are asking is whether we can still experience it without becoming these men.

Of course we become them. That is the exercise of fiction. That the passage about the hippie wakes for me is a kind of rueful proof. If they were powerful, we become powerful. If they had the words, we have the words. ‘Judge me, you chilly cunt. You dyke, you bitch, cooze, cunt, slut, gash. Happy now?’ Yes, David. Thanks for the grass.

You open the text and it wakes. This is the thing that cannot be killed. ‘Since we all breathe, all the time,’ he writes at the end of The Pale King, ‘it is amazing what happens when someone else directs you how and when to breathe.’ The novel does this, as much as any hypnotist. The rhythms of another person’s sentences do this, wind across the grid, Illinois, their attempts to keep their mother alive for all time by reproducing her idiom down to the letter. It’s in your mind now: levitation. It’s in your mouth now: Obetrolling. ‘And how vividly someone with no imagination whatsoever can see what he’s told is right there, complete with banister and rubber runners, curving down and rightward into a darkness that recedes before you.’ You open a text and it wakes. What is alive in it passes to the living. His attention becomes our attention. It can still be ours, sure. Do with it what you will.

I am not saying reading can’t be therapeutic. Of course, it can. So can mowing the lawn and baking muffins. Nor is there anything wrong with Lockwood pointing this out—and kudos to her, by the way, for defending reading David Foster Wallace at all—but I do find her approach to Wallace to be rather narrow and still largely determined by the fashionable biographical-therapeutic approach to texts today.

Speaking of the therapeutic, Alice Kemp-Habib writes against Alain de Botton’s “School of Life” publishing house, which aims to publish only novels that are psychologically “beneficial”:

Literature has long been used to educate, from the instructional wordplay of Dr Seuss to the moralising works of George Orwell. Even self-help novels have some precedent in texts such as Paulo Coehlo’s The Alchemist, but The School of Life may be the first publisher to own up to its intentions; A Voice of One’s Own is being billed as a “therapeutic novel” with explicitly practical purposes. Lubrano suggests that, in some cases, fiction is more effective than self-help in communicating such messages. “When people read a novel, there’s something freeing about the fact that the character is fictional. You can identify with them but not feel too close to them. You have a little more mental flexibility to take in new ideas without feeling defensive. [Anna is] a prop, but she’s a very thoughtful literary prop.”

Approaching literature in this manner, however, doesn’t always serve the reader. “Characters that primarily represent messages and ideas can come across as one dimensional or pedantic,” says Jolenta Greenberg, who road tests self-help books in her podcast By the Book. “When not done well, the agenda of the author and the story can almost seem to work against each other.” This is often the case with A Voice of One’s Own, where therapy-speak is inelegantly wedged into the narrative. When Anna’s habit of rejecting Nice Guys is revealed, for example, the omniscient narrator declares that “it takes a lot of self-love to forgive someone who desires us”. Such authorial pronouncements may as well come pre-highlighted.

In other news, Alexander Larman reviews Elizabeth Winkler’s Shakespeare Was a Woman: “It is undeniably true that little is known of Shakespeare’s life. The stories that are commonly recognized (the ‘second-best bed’ bequeathed to his wife; the various records of his property purchases in Stratford) say nothing about his work as a playwright, and in the absence of hard evidence, it is easy for the inquisitive—or the opportunistic—to attempt to fill this apparent vacuum with their own theories. Winkler places herself at the center of her narrative, writing breathlessly, ‘Should I write it? Did I dare? The taboo was alluring.’ Then a professor urges her to undertake the quest, and, no doubt aided by a substantial advance check, Winkler travels to England to remonstrate with the Stratfordians and to unearth the truth which hundreds of scholars, critics, and attention-seekers have failed to delve to the bottom of.”

Ruth Bloomfield writes in praise of the semi-detached home: “In 1939 George Orwell took aim at burgeoning British suburbia and its population of lower middle class lackeys in his novel Coming Up for Air, memorably describing the new homes being built on the fringes of cities as ‘semi-detached torture chambers where the poor little five-to-ten pound a-weekers quake and shiver’ . . . It’s easy to imagine that the semi – the staple backdrop of sitcoms set in the suburbs, from Mum, starring Lesley Glanville, to Ricky Gervais’s After Life – was born in the inter-war years. But in fact cojoined houses were a medieval invention. Early examples of timber framed semis from the 14th and 15th centuries have been found everywhere from Suffolk to Staffordshire.”

A Massachusetts library book is returned 119 years after it was checked out: “The book, James Clerk Maxwell’s An Elementary Treatise on Electricity, had somehow made its way to a donation pile in West Virginia, nearly 900 miles from its home at the New Bedford Free Public Library.”

Johann N. Neem reviews Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelizer’s Myth America: Historians Take On the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past: “One day early in the pandemic, when schools and colleges first went online, my undergraduate students and I had just finished discussing an essay on the rise and decline of the innovative and powerful Comanche empire. I logged off and walked downstairs, where my elementary school-aged child was sitting at the dining table. ‘What did you learn in school today?’ I asked, as I always do. He recounted to me—not in these exact words, of course—that North America had been an Edenic paradise before the Europeans arrived. I was shocked. This was the racist myth of the noble savage repackaged by the antiracist left. In reality, Native Americans did not need Europeans to introduce them to warfare, imperialism, slavery, or violence. This does not diminish the significant impact European pathogens and ambitions had on Native American polities. But to teach such distortive myths about the past? That’s the kind of thing historians should be upset about. So imagine my surprise when I opened Princeton historians Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelizer’s new edited volume on contemporary historical myths and found no essay—not a single one!—that challenged myths that came from the left.”

Those previously unknown Rembrandts found in a private collection have been sold for $14.2 million: “Depicting relatives of the Dutch master, the intimate paintings are the last Rembrandt portraits still in private hands, according to Christie’s auction house, which did not reveal the winning bidder’s identity.”

Outstanding.