Summer Books

Also: Alexis de Tocqueville in Italy, investing in Substack, the stunt work of "John Wick: Chapter 4," and more.

At the end of last year, I wrote about forthcoming spring books that looked interesting. Here are some summer books that have piqued my interest:

Nick Ripatrazone, The Habit of Poetry: The Literary Lives of Nuns in Mid-century America (Fortress, May). Nick is a wonderful writer, and I am not familiar with any of the poets in this volume, so I am much looking forward to reading it. From the jacket: “Something of a minor literary renaissance happened in midcentury America from an unexpected source. Nuns were writing poetry and being published and praised in secular venues. Their literary moment has faded into history, but it is worth revisiting.”

Nigel Biggar, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, May). This is a controversial but needed book. Biggar is an accomplished scholar and the Emeritus Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology and the Director of the McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics, and Public Life at Oxford. Other academics have tried to cancel the book and shut down his multi-year research colloquium at Oxford called Ethics and Empire, which he runs with Krishan Kumar, the William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of Sociology at the University of Virginia. From the jacket: “Biggar makes clear that, like any other long-standing state, the British Empire involved elements of injustice, sometimes appalling. On occasions it was culpably incompetent and presided over moments of dreadful tragedy. Nevertheless, from the early 1800s the Empire was committed to abolishing the slave trade in the name of a Christian conviction of the basic equality of all human beings. It ended endemic inter-tribal warfare, opened local economies to the opportunities of global trade, moderated the impact of inescapable modernisation, established the rule of law and liberal institutions such as a free press, and spent itself in defeating the murderously racist Nazi and Japanese empires in the Second World War. As encyclopaedic in historical breadth as it is penetrating in analytical depth, Colonialism offers a moral inquest into the colonial past, forensically contesting damaging falsehoods and thereby helping to rejuvenate faith in the West’s future.”

Claire Cock-Starkey, The Curious History of Weights & Measures (Oxford, May). I am a sucker for these kinds of books, and I bet some of you are, too. From the jacket: “How long is an ell? How big is the largest champagne bottle? How do you measure the heat of a chili pepper? Why is the depth of water measured in fathoms? And what, exactly, is a cubit? The Curious History of Weights & Measures tells the story of how we have come to quantify the world around us. Looking at everything from carats, pecks, and pennyweights, to firkins, baker’s dozens, and modern science-based standards such as kilograms and kilometers, this book considers both what sparked the creation of measures and why there were so many efforts to usher in standardization. Full of handy conversion charts and beautiful illustrations, The Curious History of Weights & Measures is a treasure trove of fun facts and intriguing stories about the calculations we use every day.”

Gary Saul Morson, Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter (Belknap, May). I will read pretty much anything Gary Saul Morson writes. He is one of our most gifted literary scholars. From the jacket: “Since the age of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov, Russian literature has posed questions about good and evil, moral responsibility, and human freedom with a clarity and intensity found nowhere else. In this wide-ranging meditation, Gary Saul Morson delineates intellectual debates that have coursed through two centuries of Russian writing, as the greatest thinkers of the empire and then the Soviet Union enchanted readers with their idealism, philosophical insight, and revolutionary fervor.”

Mark Braff, Sons of Baseball: Growing Up with a Major League Dad (Rowman & Littlefield, May). From the jacket: “Sons of major league baseball players grow up in a unique environment, not only because they are raised in part by professional athletes, but also because they are raised by the game itself. They come of age immersed in the distinct sounds and aromas of baseball. The locker rooms, the cinderblock-lined corridors beneath the stands, the dugouts, and the fields are the playgrounds of their youth. In Sons of Baseball, Mark Braff interviews 18 men who share their exclusive stories, ballpark memories, and the challenges and rewards of having fathers whose talents enabled them to reach the pinnacle of their profession.”

Charles Darwent, Surrealists in New York: Atelier 17 and the Birth of Abstract Expressionism (Thames and Hudson, May). From the jacket: “In 1957 the American artist Robert Motherwell made an unexpected claim: ‘I have only known two painting milieus well … the Parisian Surrealists, with whom I began painting seriously in New York in 1940, and the native movement that has come to be known as “abstract expressionism,” but which genetically would have been more properly called “abstract surrealism.”’Motherwell’s bold assertion, that abstract expressionism was neither new nor local, but born of a brief liaison between America and France, verged on the controversial. Surrealists in New York tells the story of this ‘liaison’ and the European exiles who bought Surrealism with them.”

Joseph Epstein, The Novel, Who Needs It? (Encounter, July). From the jacket: “In this brief but highly engaging book Joseph Epstein argues for the primacy of fiction, and specifically of the novel, among all intellectual endeavors that seek to describe the behavior of human beings. Reading superior fiction, he holds, arouses the mind in a way that nothing else quite does. He shows how the novel at its best operates above the level of ideas in favor of taking up the truths of the heart. No other form probes so deeply into that eternal mystery of mysteries, human nature, than does the novel.”

Rebecca Struthers, Hands of Time: A Watchmaker’s History (Harper, July). From the jacket: “Timepieces have long accompanied us on our travels, from the depths of the oceans to the summit of Everest, the ice of the arctic to the sands of the deserts, outer space to the surface of the moon. The watch has sculpted the social and economic development of modern society; it is an object that, when disassembled, can give us new insights both into the motivations of inventors and craftsmen of the past, and, into the lives of the people who treasured them. Hands of Time is a journey through watchmaking history, from the earliest attempts at time-keeping, to the breakthrough in engineering that gave us the first watch, to today – where the timepieces hold cultural and historical significance beyond what its first creators could have imagined.” Struthers is a watchmaker herself.

Kate Kennedy, Dweller in Shadows: A Life of Ivor Gurney (Princeton, July). From the jacket: “Ivor Gurney (1890–1937) wrote some of the most anthologized poems of the First World War and composed some of the greatest works in the English song repertoire, such as ‘Sleep.’ Yet his life was shadowed by the trauma of the war and mental illness, and he spent his last fifteen years confined to a mental asylum. In Dweller in Shadows, Kate Kennedy presents the first comprehensive biography of this extraordinary and misunderstood artist.”

John McPhee, Tabula Rasa: Volume 1 (FSG, July). From the jacket: “Over seven decades, John McPhee has set a standard for literary nonfiction. Assaying mountain ranges, bark canoes, experimental aircraft, the Swiss Army, geophysical hot spots, ocean shipping, shad fishing, dissident art in the Soviet Union, and an even wider variety of other subjects, he has consistently written narrative pieces of immaculate design. In Tabula Rasa, Volume 1, McPhee looks back at his career from the vantage point of his desk drawer, reflecting wryly upon projects he once planned to do but never got around to―people to profile, regions he meant to portray. There are so many examples that he plans to go on writing these vignettes, an ideal project for an old man, he says, and a ‘reminiscent montage’ from a writing life.”

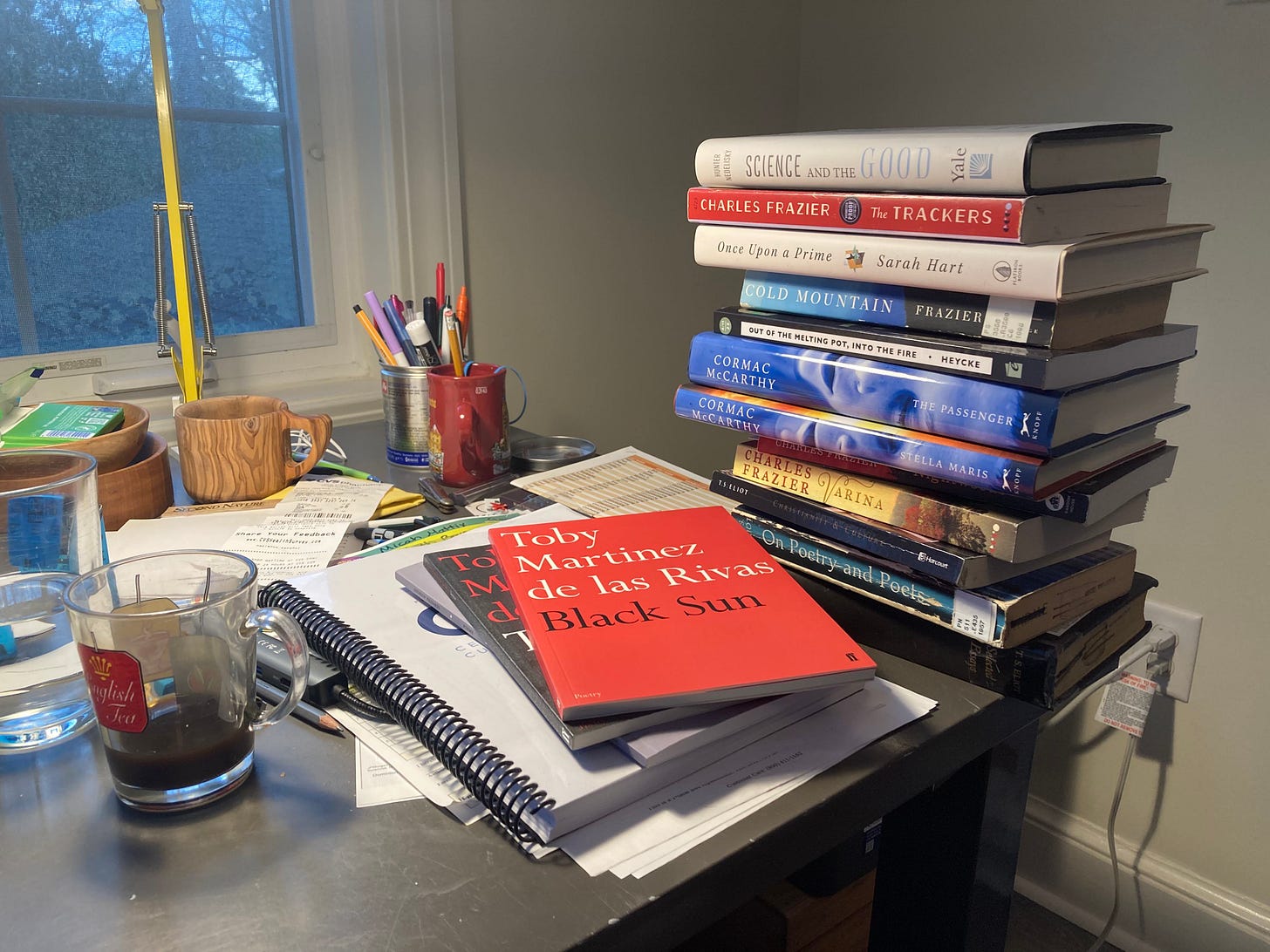

Toby Martinez de las Rivas, Floodmeadow (Faber & Faber, July). Before canceling other writers became a thing, the critic Dave Coates accused Toby Martinez de las Rivas of fascism after reading his poem “Titan / All Is Still” way back in 2017. It was a ridiculous accusation. Martinez de las Rivas responded to the accusation here, and the critic Henry King wrote of refutation of Coates’s reading of the pom in PN Review. The poem has one of the most touching and probing sequences in contemporary poetry of a father contemplating the afterlife, and while Martinez de las Rivas can, at times, be elliptical and obscure in a posturing sort of way, he can also write poems of real beauty and power. I am looking forward to his latest collection, which is his third. From the jacket: “Floodmeadow draws us into a seething pastoral where lightning threatens and thunder gathers, pylons and powerlines hum, and steel-framed gates sing out into the wind. In these incantatory pieces, everything is present at once. The landscape, teetering on apocalypse, is characterised by collision and disintegration. Among fragments of memory and history are meticulously journaled observations of the natural world: the moorhen who ‘with exaggerated delicacy steps / free of the reedbeds’; the dragonfly that ‘pushes itself through the armour / of its body’ to be born.”

Stephen Fry, Fry’s Ties: The Life and Times of a Tie Collection (Chronicle, August). Why not? From the jacket: “In this utterly charming volume, Stephen Fry excavates his epic collection of neckties and shares the stories behind them. From the traditional ‘egg and bacon’ colors of the Marylebone Cricket Club to the exuberant Dalmatian pattern of a 1980s Nicole Miller design, each tie tells a story. Interspersed amongst the collection are diagrams to aid in tying your own Half Windsor, Van Wijk, or Prince Albert Knot.”

Sarah Ruden, Vergil: The Poet’s Life (Yale, August). From the jacket: “Sarah Ruden, widely praised for her translation of the Aeneid, uses evidence from Roman life and history alongside Vergil’s own writings to make careful deductions to reconstruct his life. Through her intimate knowledge of Vergil’s work, she brings to life a poet who was committed to creating something astonishingly new and memorable, even at great personal cost.”

In other news, Matt Mullins reviews Reza Aslan’s An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville: “Reza Aslan—professor, pundit, and bestselling author—is on a mission. That mission is essentially to convince the world that humanity is capacious enough for the most hostile enemies to work together to achieve a common peace, even as they hold tight to their respective histories, traditions, and convictions. Throughout his work, he praises examples of people laboring alongside one another in the pursuit of freedom and self-determination across differences of race, class, language, nation, and—most importantly—religion. These ideals are not merely political for Aslan, they are spiritual as well, radiating from the transcendent truth that ultimately unites the immanent truths of our diverse human traditions. In his latest book, An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville, Aslan expresses this complicated faith through the story of a fellow traveler and unlikely hero: an early-20th-century American evangelical missionary to Persia.”

Alexis de Tocqueville in Italy: “In March 1850 Alexis de Tocqueville developed the first overt symptoms of the tuberculosis that was to kill him nine years later. Writing to poet and politician Richard Monckton Milnes from Paris in April he informed him that ‘for the last six months our house has been a veritable place of misery. When the wife recovers, the husband falls ill, and thus it continues.’ And so it was that Tocqueville applied for leave of absence for six months from his parliamentary duties and that he returned to convalesce in Tocqueville. If, despite his initial concerns, the long journey from Paris to Normandy had no adverse consequences (the sea between Le Havre and Cherbourg, Tocqueville recorded, was ‘a little choppy’ but, for once, with no ill effect on his stomach), by early July he could report to politician Francisque de Corcelle that, although not fully recovered, his health was improving. A month later he told Corcelle that he was ‘visibly returning to the condition he was in before the spitting of blood.’”

Angélique Kidjo, Chris Blackwell, and Arvo Pärt—my favorite contemporary composer—win Sweden’s Polar Music Prize: “The Polar Music Prize is awarded annually to individuals, groups and institutions in recognition of exceptional music achievements. It includes a cash award of 600,000 kronor ($57,700) each. An awards ceremony is scheduled for May 23 in Stockholm.”

The Texas Observer closes its doors: “The 68-year-old progressive publication, which published Ronnie Dugger, Molly Ivins and Kaye Northcott, hit financial troubles and wasn’t able to broaden its audience, board members said.”

My son and I have watched the first three John Wick films, and we will watch the fourth one next time he visits. John Podhoretz praises the film: “John Wick: Chapter 4 opens with an homage to the most famous shot in Lawrence of Arabia, as Laurence Fishburne blows out a match in New York and the movie slam-cuts to a shot of the desert in North Africa. Director Chad Stahelski is making an announcement here: The little B-movie he made in 2014 called John Wick, about a grieving suburban widower and retired mob assassin who takes revenge for the killing of his dog, has birthed an epic. The second and third installments of the franchise took Keanu Reeves's John Wick out of New York and into Europe and Asia and Morocco in search of more people to kill. But the sheer scale of John Wick 4 dwarfs those lesser sequels in impact and jaw-dropping effect. Not only that, it pretty much dwarfs any other action movie made in the past 10 years aside from Mission: Impossible—Fallout.”

And Miles Surrey writes about the difficult stunt work that went into making the film: As with any action-oriented blockbuster, there’s an audience expectation that future sequels will up the ante. But for John Wick, in particular, that’s easier said than done. While other tentpoles can utilize special effects to help take the action to new heights (see: F9 sending a Pontiac Fiero into outer space), the John Wick movies are defined by their commitment to practical stunt work and complex fight choreography . . . If there’s a limit to how much one man can actually do, then Chapter 4 certainly takes its title character—and, by extension, Reeves—to the brink.”

Carl R. Trueman reviews Roger Scruton’s journalism: “When Roger Scruton died in early 2020, the world lost a philosopher with that rarest of gifts: the ability to express profound ideas in elegant and limpid prose. It also lost the man who more than any other in his generation had sought to develop a positive conservative philosophy, eschewing both the naive confidence that the free market would solve all problems and the temptation to reaction and authoritarianism. His death also robbed us of his thoughts on the impact of Covid, with its cult of the expert and manipulative use of social media, and the surge of social unrest in Europe and North America. This background makes the latest (though one hopes not the last) collection of Scruton’s shorter writings rather moving. One cannot read them without a sense that the conservative world lost a learned, thoughtful, and creative voice at the very moment when it was most needed.”

In his early work, William Logan writes, W. H. Auden “succumbed to inflated phrase-making.” His later poems were “written in the study and for the study”: “Auden’s cleverness, his knack for savage opening lines, his sorcerer’s touch with form—all these can be appreciated, yet he now rarely enters what is called, rather stupidly, the ‘conversation.’ Was he too formal (in manner as well as form), too high churchy and high arty, simply too measured for later ears? Or is he out of date, his poems not tuned to contemporary taste? Auden was the same generation as Elizabeth Bishop, born just four years after him; yet she speaks to a century a century later as he does not.” Is this a fair assessment of Auden?

Substack is giving writers and subscribers the opportunity to invest in the company. Ted Gioia explains why he is investing. Read more about the opportunity here.

Logan’s Auden review is the worst kind of review: eager to show off superior judgment and would-be witty turns of phrase. While he isn’t wrong about some things (Auden’s long poems aren’t, generally speaking, him at his finest), it reads like someone writing under the influence of the worst of Auden, musing about the worst of Auden. I’m too far removed from academia to know whether Elizabeth Bishop has somehow outstripped Auden’s reputation there, but in the world at large, Auden seems to come up more often than most poets as a cultural touchstone (“Sept 1, 1939” in the aftermath of 9/11, for example). Nothing against Bishop — her “One Art” is perhaps my favorite villanelle. But I don’t think I’ve ever seen her referenced outside academia.

Thank you. Just preordered two of those!