Saturday Links

The cut and thrust of Victorian weeklies, Victorian female detectives, moving mushrooms, Flannery O’Connor in New York, and more.

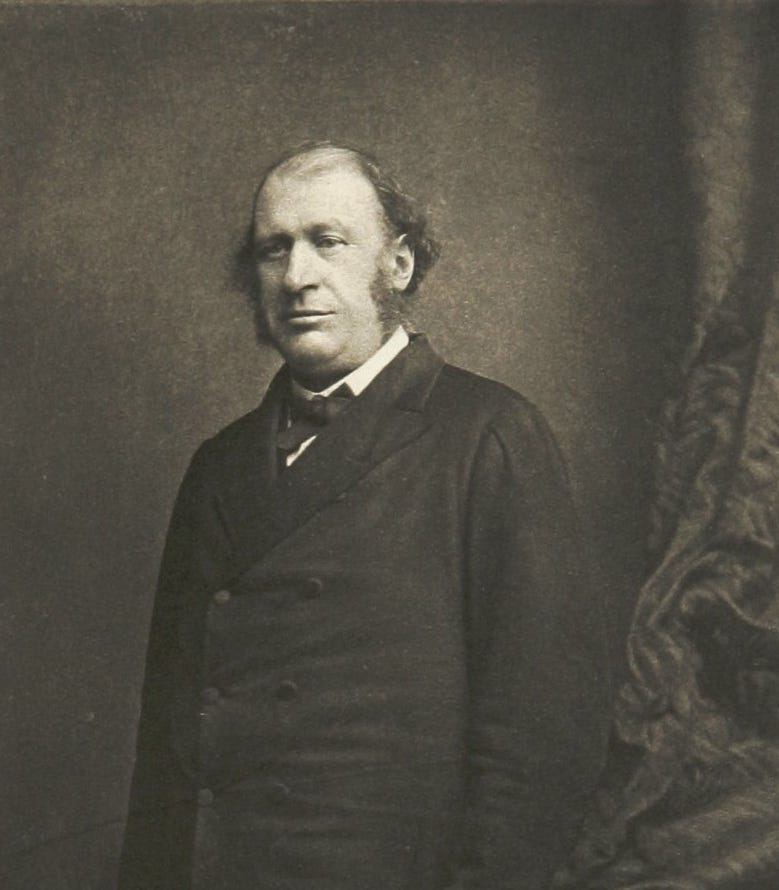

Good morning! The introduction of the weekly magazine in Britain changed criticism. British quarterlies were “stately,” but the new weeklies were fiercely independent with “a special antipathy to popular humbugs of every kind,” or so they characterized themselves. Few writers for these new weeklies were more fiercely independent than James Fitzjames Stephen:

Changes in the technology of paper-making and printing combined with the growth of new markets to make periodicals potentially more profitable; scarcely less important were the first steps towards the establishment of a national railway network to speed up distribution. Beyond these changes in material conditions, there was also a shift in the public perception of ‘journalism’ (a coinage of the 1830s, imported from France). Those who wrote for daily or weekly newspapers in the late 18th century were generally looked down on as hacks, whereas the contributors to the quarterlies were seen as gentlemen (they were mostly, though not exclusively, male). They were members of the professional rather than the landed class, but still eligible for membership of the clubs that provided an important market for these publications. In addition, the revival of Oxford and Cambridge from the 1840s onwards generated a steady supply of articulate young men in search of a career. A graduate with a fluent pen who found the Bar too chancy, the civil service too dreary, and the Church too churchy could earn a decent living in mid-Victorian Britain if he published enough articles in the right places.

The Saturday Review led the way in exploiting these conditions, and it was soon joined by the new monthly magazines that were such a feature of mid-Victorian literary and intellectual life, such as the Cornhill, Macmillan’s, the Fortnightly Review (a monthly for most of its life, despite its name) and so on. By more recent standards, the new weekly offered strenuous stuff, the uninterrupted columns of print moving from the opening political leaders through to the longer ‘middle’ (a substantial opinion essay) and on to the unsparing book reviews. But what really distinguished the Saturday was its tone – self-consciously unillusioned, unsentimental, exacting, a tone that announced the presence of high-quality butchers specialising in the sacred cows of the age. ‘On Sunday the paper became part of the breakfast,’ the critic and novelist Walter Besant recalled; ‘it was read with savage joy’ . . . There was no more representative ‘Saturday Reviler’ than Leslie Stephen’s older brother, James Fitzjames Stephen.

Speaking of Victorians, Sara Lodge investigates the mysterious case of the Victorian female detective: “‘If there is an occupation for which women are utterly unfitted, it is that of the detective,’ claimed the Manchester Weekly Times in 1888 – already behind the times, it seems, as women had been acting the part for years, albeit invisibly. They had started to feature in detective fiction too. It was studying the burgeoning market in ‘lady detective’ stories post-1860 that led Sara Lodge to wonder who the fantasy sleuths were modelled on, and why the Victorians found them so disturbing and alluring.”

Moving mushrooms: “Engineers have created a new type of robot that places living fungi behind the controls. The biohybrid robot uses electrical signals from an edible type of mushroom called a king trumpet in order to move around and sense its environment. Developed by an interdisciplinary team from Cornell University in the US and Florence University in Italy, the machine could herald a new era of living robotics.

Scholars continue to decipher the carbonized scrolls discovered in Herculaneum near Pompeii. How might our understanding of the ancient world change? Justin Germain considers: “We know about dozens of Greek playwrights who were famous in antiquity, but of whose work we don’t have a single fragment. What of Ptolemy’s history of Alexander the Great? We know he wrote one because Arrian, who wrote the only full history of Alexander we have, claims to have used it as a source. What about the great culture of the Carthaginians, whose poetry and philosophy, we are told, were all over the Mediterranean prior to Rome’s final destruction of the city and erasure of their culture in 146 BC? What could we learn about the Punic Wars if we found a Carthaginian history of the conflict? What else might be waiting for us out there and how might that add to our perception of ancient history?”

Poem: Morri Creech, “A Letter from Rome”

Richard Kreitner reviews the biography of a Jewish poet from Savannah during the Civil War:

In 2016, Jason K. Friedman, a fiction writer from Savannah, Georgia, then living in San Francisco, decided to buy an apartment in an old townhouse in the historic district of his native city. He was drawn in by the name given for the building—the Solomon Cohen townhouse. Not many of the celebrated historic homes of Savannah carry Jewish names. The apartment seemed like a solid investment, since he and his husband could rent it out to tourists. From the West Coast, they put in a bid, sight unseen.

When Friedman first visited his new property, he opened a kitchen drawer and found a document with details of Cohen’s colorful biography—talented lawyer, founder and director of railroads and banks, influential Georgia politico and reluctant secessionist, real-estate impresario who built the townhouse a decade after the end of the Civil War. Friedman became particularly fascinated, however, by Solomon’s only son, Gratz, the first Jewish student at the University of Virginia, a sensitive poet, who was apparently gay. After years of avoiding enlistment in the Confederate Army on account of a debilitating foot injury, Gratz finally leapt into the fray only to die in battle just weeks before Appomattox. Friedman decided to dig up everything he could about the brief life of Gratz Cohen, an intriguing and impressive young man, confused by his own emotions and overwhelmed by the enormity of the war.

I review a new book on Flannery O’Connor’s supposed debt to Manhattan. There is just one problem with the book. New York City—as a place—simply wasn’t that important to her:

Laborde claims that O’Connor’s Manhattan “is made up of more than the names and places” in O’Connor’s address books, which Laborde lists in the book, but “of what happened and what didn’t. Of what she experienced and what she merely thought about.” But not much happened in New York, and while the city may still have left a mark on her writing in some way, Laborde doesn’t discuss this in any detail.

The fact is that O’Connor didn’t seem to care for the city at all. Her initial trip there as an adult (she visited once as a child) was unplanned, and she left as quickly as she could—to stay with the Fitzgeralds in Connecticut only six months after arriving in the city and meeting them for the first time. Maryat Lee tried to convince O’Connor to visit . . . but O’Connor never does, even though she visits other places during the same time—Chicago, Nashville, Minnesota, Louisiana, Texas, and St. Louis.

Andrew Ferguson reviews Griffin Dunne’s memoir, The Friday Afternoon Club: “Like the life of the family he portrays with such affection and humor, The Friday Afternoon Club is divided into two parts. The first and longest is a rollicking account of a charmed childhood in 1950s and ’60s Hollywood, followed by the struggles of a young boho actor in Manhattan. No reader will want the first part to end, I reckon, except to see what could possibly come next—which, unfortunately, is the second part, an account of the murder of Dunne’s sister and the trial of her murderer. A brief coda at the book’s close lifts us out of the heartbreak and drops us gently on the other side, with an account of the birth of Dunne’s first child. It’s the quick and lovely ending to a wise and lovely book.”

You’ve likely read about Darryl Cooper’s comment in an interview with Tucker Carlson that Winston Churchill “was the chief villain of World War II.” Andrew Roberts responds in The Washington Free Beacon that it would “be both interesting and indeed shocking were his thesis not based on such staggering ignorance and disregard for historical fact that it is safe to disregard completely.”

Matthew Walther considers the larger problem of the widening gap between real historians and the reading public in Compact. Cooper’s career, Walther writes, “suggests that we are no longer faced with a gap between specialist knowledge and what remains of the reading public, to be spanned by belletristic popularizers; but one between historians who write without any hope of reception, much less wealth or literary fame, and a very different, more or less post-literate audience who would prefer that whatever historical edification they might receive come via podcast or even tweet.”

A musician in North Carolina is arrested for fraud: “A North Carolina musician was arrested and charged Wednesday with using artificial intelligence to create hundreds of thousands of songs that he streamed billions of times to collect over $10 million in royalty payments, authorities in New York said. Michael Smith, 52, of Cornelius, North Carolina, was arrested on fraud and conspiracy charges that carry a potential penalty of up to 60 years in prison.”

Forthcoming: April Lindner and Ryan Wilson, editors, Contemporary Catholic Poetry (Iron Press, September 10): “Featuring 23 contemporary Catholic poets, from Julia Alvarez and Carolyn Forché to Timothy Murphy and Franz Wright, this anthology is an essential collection that captures the spectrum of the Catholic experience.”

I’m late to the party as I was visiting a cousin in Rhode Island (interesting mini state, where do their tax dollars go?). Anyway, regarding con artist Michael Smith: I just evaluated his M.O. and in my semi-expert opinion, he had to work HARD for his ill-gotten gains. Hard to distinguish him from some now wealthy tech entrepreneurs from the turn of this century!