Saturday Links

The big danger with “little data,” in praise of puzzling, homeless in America, Martha Gies’s essays, and more.

Good morning! Patrick Fealey, a former art critic for The Boston Globe, now lives in his car in Rhode Island. He writes about what it’s like to be homeless in America in Esquire: “My morning routine is taking gabapentin (an anti-seizure medication that also alleviates psychic and neuropathic pain and brightens my perception), lamotrigine (another anti-seizure medicine, but for me it helps my mental energy and cuts through fog, because gabapentin creates fog), fluoxetine (Prozac, an antidepressant), and Adderall (for focus and energy, because after the manic depression struck in 1997, my brain was a flat tire), walking the beach with Lily, getting coffee at the Mobil station up the road, and writing on an HP laptop I got two months ago that has already had one power-input jack fail. It sits on an upside-down acoustic guitar resting on my lap, a 12V/120V converter plugged into the lighter with the car running. I play the guitar first thing every morning, songs I’ve written. The rest of the day, I flip it over and it’s my desk . . . I go to Walmart that night and will sleep there every night. But the police will continue to come as if I’m some kind of one-man crime wave. Before I’m chased out of Westerly, I will meet, stand my ground, and lose ground to a dozen different officers, often at night, banging on my window and waking me just to ask, ‘Are you all right?’ The question begins to sound like a pretense. The officers are civil, but every encounter causes me apprehension and stress. I’m innocent of any wrongdoing, but the interaction between a citizen and law enforcement is unbalanced by nature.”

Remembering the rogue philosophers of Dubrovnik’s Inter-University Centre (IUC):

In 1986, my quiet life as a doctoral student in philosophy was punctuated by a trip to Brno in Czechoslovakia (as it then was), where I found myself in a high-speed, chicken-scattering taxi, chasing a bus before it reached the border. It was my small part in a larger story of philosophers’ derring-do during the Cold War.

The Oxford philosopher of science Bill Newton-Smith had been arrested prior to my trip in the middle of a talk in Prague, taken to secret police headquarters for interrogation, then driven in a convoy through the snowy night to the West German frontier and expelled. The French deconstructionist Jacques Derrida had been followed for days, drugs were planted in his suitcase, and he was briefly arrested and detained at the border as a smuggler . . . The IUC was founded by 30 universities in 1972, under the leadership of the physicist Ivan Supek, at the time rector of the University of Zagreb. Tito’s Yugoslavia, not aligned with the Soviet Union but communist enough to please it, provided neutral ground where academics from Warsaw Pact countries could meet their colleagues from the West. The IUC arranged conferences and courses in the humanities and social sciences, and soon moved into the natural sciences and medicine. There were some constraints.”

Nicolas Carr writes about the big danger with “little data” in The Hedgehog Review:

Clean and tidy, the mirror world has practical value. It makes life run more smoothly. If I know I’m going to have to sign for a package, it’s useful to be told when it will arrive. If I’m on a highway and I’m alerted to an accident ahead, I can take an exit before I get stuck in a traffic jam. If I know rain is going to start falling in seventeen minutes, I can put off the walk I was about to take. But the view of reality that little data give us is narrow and distorted. The image in the mirror has low resolution. It obscures more than it reveals. Data can show us only what can be made explicit. Anything that can’t be reduced to the zeroes and ones that run through computers gets pruned away. What we don’t see when we see the world as information are qualities of being—ambiguity, contingency, mystery, beauty—that demand perceptual and emotional depth and the full engagement of the senses and the imagination. It hardly seems a coincidence that we find ourselves uncomfortable discussing or even acknowledging such qualities today. In their open-endedness, they defy datafication.

Still, little data’s simplifications are reassuring. By shrinking the world to the well-defined and the measurable, they lend a sense of order and predictability to our disjointed lives. Social situations used to be bounded in space and time. You’d be in one place, with one group of people, and then, sometime later, you’d be somewhere else, with another group. Such “situation segregation” served as “a psycho-social shock absorber,” the communication professor Joshua Meyrowitz explained in his 1986 book, No Sense of Place. “By selectively exposing ourselves to events and other people, we control the flow of our actions and emotions.” Social media eliminates the spatiotemporal boundaries. Social settings blur together. We’re everywhere, with everyone, all at once. The shock absorber gone, a welter of overlapping events and conversations buffets the nervous system. Time stamps, progress bars, location mappings, and other such informational indicators help temper the anxiousness bred by the flux. They give us a feeling that we’re still situated in time and space, that we exist in a solid world of things rather than a vaporous one of symbols. The feeling may be an illusion—the information offers only a sterile representation of the real—but it’s comforting nonetheless. My shirt is in Tacoma, and all is right in the world.

The comfort is welcome. It’s one reason the data exert such a pull on us. But there’s a bigger reason. Little data tell us little stories in which we play starring roles. When I track a package as it hopscotches across the country from depot to depot, I know that I’m the prime mover in the process—the one who set it in motion and the one who, when I tear open the box, will bring it to a close . . . And yet, as we rely on the data to get our bearings and exercise our agency, we lose definition as individuals. The self, always hazy, dissolves into abstraction. We begin to exist symbolically, a pattern of information within a broader pattern of information.

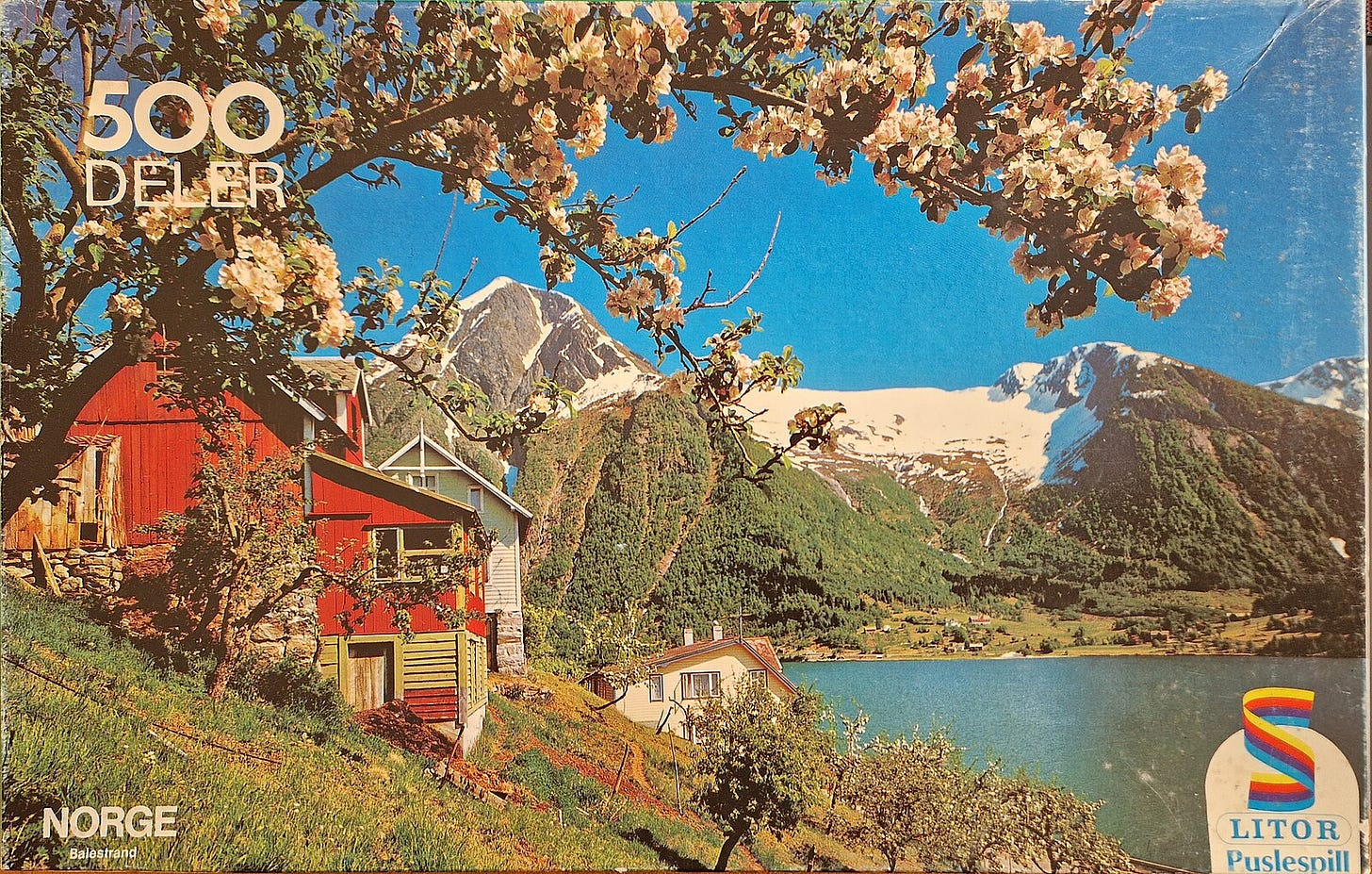

I like to work on a good puzzle, especially over Thanksgiving and Christmas. John Wilson didn’t—until recently: “The companionship and the routine of our puzzling are comforting. (I am a great lover of routine, perhaps to excess.) Above all, as I suggested when I wrote that column a year ago, we are thankful for the blessed order that even a 300-piece jigsaw puzzle (decidedly “corny” in the judgment of many observers, and trivial to boot) instantiates. We proceed in the faith that, ultimately, everything will “fit” in the grand scheme of things, everything will have its place, and from the heap of pieces we pour out onto the card table an ordered scene will take shape, a microcosm of the whole shebang in which we too are part of the picture.”

In praise of six-on-six: “Six-player basketball, which became popular nationwide in the 1930s but survived only in Iowa and Oklahoma by the fin de siècle, posted three girls in the frontcourt — the forwards, who shot the ball — and three guards in the backcourt, where ball-handling and defense were prized. Players could not cross the center line and were limited to two dribbles at a time. A distinctive game grew around these rules, emphasizing crisp passing and deadeye shooting.”

Poem: Lynne Knight, “The Hour of the Wolf”

Can you make six figures publishing public domain classics? Kevin Kearney investigates: “Tiffany Miller, who’s in her late 30s and previously worked as a bartender in northern New Jersey, said she made about $2,000 every month after working at publishing for two years. She was so amazed by her success that she’d convinced her 13-year-old daughter to open an account. Dan Baker, who’s 50 and works full-time as a forklift operator outside of Sydney, has only made about $2,000 total after two years of work, but he told me he didn’t plan on stopping any time soon. He knew it was only a matter of time until his luck changed. ‘It’s like a lottery ticket,’ he explained. Like me, Miller and Baker found Pye online. They’d watched all the same videos I had and had firsthand experiences suggesting Pye’s estimates were overblown, but both were still upbeat. There was money coming in. Neither considered themselves readers, though they’d still managed to find some success as publishers of classic literature.”

Rod Dreher writes about the €44 million renovation of St Hedwig’s Cathedral in Berlin: “The interior of the vast structure has been stripped utterly bare, its interior an all-white canvas of nothingness. It is so vacant of any sign of not only the Catholic faith, but of Christianity itself, that even a strict Calvinist would be left puzzled over which God is worshiped inside this whitewashed modernist sepulcher, this costly monument to the Void.”

I review Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II in the new issue of The Washington Examiner. I loved the first Gladiator and was hoping for a solid sequel, but the film was disappointing:

The acting is mostly underwhelming. Both Joseph Quinn and Fred Hechinger go all out to give us emperors who are effectively grotesque, but everyone else besides Denzel looks bored. The film’s dialogue is written in a mix of modern English and faux Elizabethan (“What say you?”). The actors are unsure if they should speak these lines in a British accent or not. Pascal gives the king’s tongue a half-hearted try but quickly gives up. Denzel speaks Denzel throughout, though he has the film’s corniest line: “Rage pours out of you like milk from a whore’s tit,” he tells Lucius.

Lucius repeats many of Maximus’s defining phrases (“On me!”) and gestures — he rubs his hands in gravel or chalk a half-dozen times. This is supposed to be suggestive of the film’s big reveal, that Lucius is Maximus’s son, but the repetitions are tiresome nonetheless. Otherwise, Lucius’s lines are either banal (“Wood or steel, a point is still a point”) or shamanistic (“Know this: Where death is, we are not. Where we are, death is not!”). The second is a crib from Epicurus about how death and consciousness cannot coexist, making death a kind of nothingness. It’s a little too highbrow, needless to say, to rally a group of gladiators to battle. Mescal delivers all of these lines in a surprisingly consistent monotone.

Also in The Washington Examiner, Alexander Larman reviews the first volume of Cher’s surprisingly readable memoir: “One of the more likable qualities of the clunkily titled Cher: The Memoir, Part One is that its author appears to have taken great delight in writing it. Cher guides the reader through the first half of her inimitable life and career with chutzpah. She begins with her impoverished and often miserable childhood in California, proceeds into the years of musical stardom, and concludes with a cliffhanger of sorts, with our hero on the verge of her Eighties acting career. We shall have to wait until the publication of Part Two next year to read her thoughts on everything from her Oscar-winning appearance in Moonstruck to her musical comebacks, disappointments, and yet more comebacks in the subsequent decades. Still, as her publicity states quite accurately, hers has been ‘a life too immense for one book.’”

Valerie Sayers reviews Martha Gies’s new collection of essays, Broken Open: “‘There was no religion in my family. My parents believed salvation lay in keeping the romance alive in their marriage, and in maintaining a high economic standard of living.’ Thus begins the essay ‘Heart of Wisdom’ in Martha Gies’s beautiful, devastating, ebullient collection, Broken Open. Readers, too, may find themselves broken open by Gies’s account of her youngest sister, Toni, who at nineteen shocks her family by becoming an evangelical Christian. The family, Gies reports drily, is ‘appalled.’”

Cartoon: The John le Carré Advent Calendar