Saturday Links

Joseph Epstein on rest, Joseph Bottum on Baudelaire, Tony Tulathimutte’s stories, the Bic Four-Color pen, and more.

Good afternoon! I am off to a late start today. I didn’t set an alarm and woke up later than I thought I would and then got distracted looking at cheap used cars in Switzerland for our upcoming move (more on that another day). But better late than never.

Let’s kick things off this afternoon with Craig Raine’s short piece on titles in Spectator: “In 1979, I was in the George pub outside the BBC with Seamus Heaney. It was the first time we had met. We were discussing titles. He liked A Martian Sends a Postcard Home as a title. He said he was getting together a book of reviews and lectures (which later became Preoccupations). He thought a good title would be Siftings: ‘you know, Hopkins, “soft sift/ In a hourglass.”’ Or, I said, ‘let their liquid siftings fall/ To stain the stiff dishonored shroud.’ That was my first (unofficial) editorial transaction with him. I remember his rueful laugh. (Incidentally, “stiff” is a rich adjective, rigor mortis transferred to the shroud.)”

Victoria Moul writes about the 1976 anthology Hardy to Hughes. Selections from Twelve Poets of the Twentieth Century, which does not include T.S. Eliot or any women:

There’s something especially fascinating about outdated anthologies. This particular one is an unpretentious but carefully curated collection, aimed at school use — there’s no preface or introduction, but there are brief biographical notes on the poets at the back and suggested questions for each of them. The twelve poets are Thomas Hardy, Wilfred Owen, Robert Graves, D. H. Lawrence, W. H. Auden, Louis Macneice, John Betjeman, Philip Larkin, R. S. Thomas, Laurie Lee, Charles Causley and Ted Hughes. They are pretty equally represented, all with between nine and 16 poems: enough to get a real feel for what they are doing and how they are doing it, and the suggested questions repeatedly invite you to compare one poet to another.

This selection is in some ways quite conventional — any survey of British poetry in the 20th century ending-in-the-70s should surely have Auden, Macneice and Larkin, and it is a bit of a commonplace of university courses and introductory books to begin such surveys with Hardy. I think it’s an excellent anthology in lots of ways, and I very much enjoyed reading it, though it prompted several thoughts about how our sense of what “English poetry” is has changed over the last fifty years.

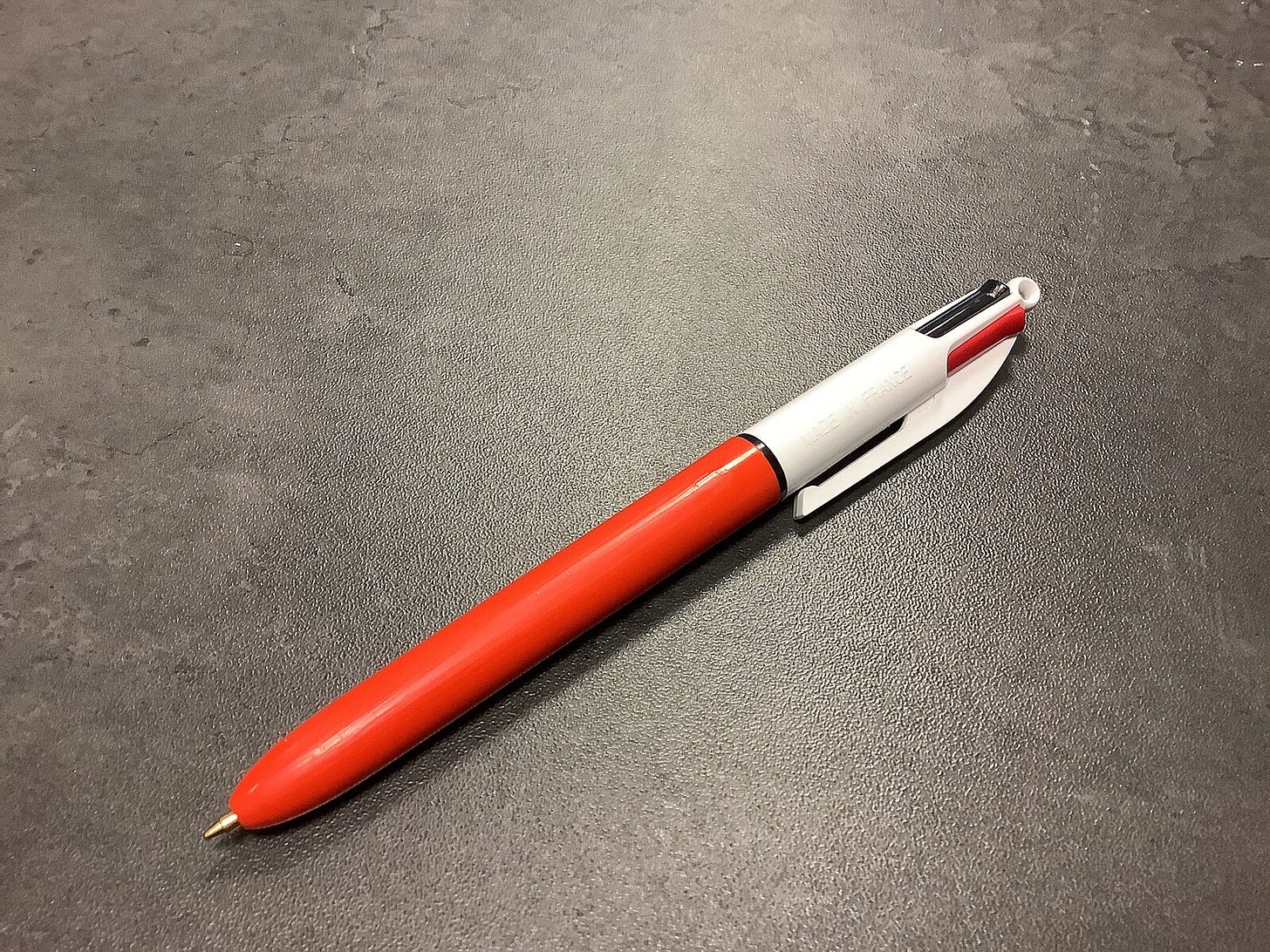

Muriel Zagha writes about the revolutionary Bic 4-Colour ballpoint pen:

What is the history of this remarkable pen? Although it was produced by a team of designers and engineers, the innovative multicolour ballpoint was the inspiration of one man, design pioneer and industrialist Marcel Bich, who gave to Bic, the brand he created, a simplified version of his name. Born in Turin in 1914, Baron Bich (a title granted in 1841 to his great-grandfather by King Charles-Albert of Sardinia) came from a line of civil engineers. He grew up in France, where after taking a law degree he began a career in industry, first gaining experience in the manufacturing of ink.

In 1945, with fellow ink technician Edouard Buffard, Bich set up his first company, manufacturing parts for fountain pens, and then, in an inspired move, acquired the patent of the ballpoint pen invented by Hungarian designer László Biró. Bich believed he could improve Biró’s design and in 1950, he and Buffard launched their first revolutionary product, the Bic Cristal. It is an exceptionally reliable and still widely used ballpoint pen, with a transparent plastic body of hexagonal shape, reminiscent of a pencil, which made it possible to monitor ink levels. Modern, affordable and – a desirable quality in those early days of plastic use – disposable, the Cristal’s success made Bic the global leader in ballpoint pens. More innovations (and more plastic) followed: a disposable lighter with adjustable flame and later a disposable razor.

When it was released in 1970, the 4-Colour retractable Bic ballpoint had behind it the impressive track record and innovative heft of the brand. Besides, the 4-Colour pen was not only a pen, but also a pleasing novelty object: a small handheld machine for changing colours. Precise springs allow the desired colour to be selected mechanically by retracting or extending a tip. The body of the pen is made of highly resilient plastics that can withstand thousands of these push-button activations. The highly viscous quality of the ink makes it possible for each 4-Colour pen to write 8 kms of lines – or 2 kms per individual colour. Over time, thankfully, the colour cartridges have also become refillable.

If you missed John Wilson’s excellent column on forthcoming fiction for this newsletter, you can read it here. John makes a number of intriguing recommendations:

Michael Connelly has a novel coming in May, Nightshade, in which he will introduce a new protagonist. I’ll devour this book within 24 hours of its arrival. Connelly, who will turn sixty-nine in July, is a marvel, a national treasure. I love interesting sentences, whether in fiction or “nonfiction”; that’s part of the reason I have spent a substantial chunk of my life reading. I’m not sure that Connelly has ever written an interesting sentence. But he has written one compelling novel after another, starting with his first, The Black Echo, in 1992, and he’s never lost his moral compass. Like his signature protagonist, Harry Bosch, he’s driven, in the best sense, and we’re the beneficiaries.

Also coming in May is Andrey Kurkov’s The Stolen Heart, translated by Boris Dralyuk, the second novel in the crime-fiction series that began with The Silver Bone. Kurkov is one of Ukraine’s foremost writers; Dralyuk, in addition to being a superb poet, is much in demand as a translator. I’ve mentioned this novel earlier, but now is a good moment to bring it to your attention again.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Prufrock to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.