Saturday Links

Robert Frost’s life in poetry, P.G. Wodehouse in America, Homer’s dogs, men and fiction, Europe's disappearing farmers, Marion Milner's method, and more.

Good morning! In the latest issue of The New Criterion, Ian Wardropper visits the many homes of the Fricks: “Visitors to The Frick Collection often ask how Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919) became a collector. How did such a rough-and-tumble businessman learn about art? Did he have advisors, or did he make his own choices? An examination of Frick and his houses will help to shed light on his collection and the museum created out of his final home.”

I review Adam Plunkett’s excellent new book on Robert Frost in the latest issue of The Washington Examiner:

The image of Frost today is still largely that of Thompson’s three-volume biography of the poet — a selfish and fault-finding man who can’t be trusted. Frost told Thompson about the affair when Thompson visited him in Key West. Thompson told Kay to end it: “There is no way to satisfy the fierceness of his demanding and demanding.”

There have been several attempts at recovery since. Jay Parini was the first to offer a corrective to Thompson’s account of Frost as little more than a misogynist in Robert Frost: A Life (2020). Frost’s complete letters (now in their third volume) show Frost to be a showman, sure, but also a faithful friend and father. Frost’s granddaughter, Lesley Lee Francis, remembers him as a complex man who cared deeply for the women in his life. British critic Tim Kendall reminded us of why we love Frost by taking us back to his work in The Art of Robert Frost (2013).

Plunkett’s Love and Need, for its part, offers something of a recuperation of the poet by reminding us that Frost’s fierceness is also a source of the considerable power of his work. There are no revelations in Love and Need, but Plunkett excels at bringing the poems to life with contextual details

Anthony Domestico also praises it in The Washington Post: “Was Frost any good? Poetically speaking, yes. Morally speaking, not always, and in his excellent new biography, Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry, critic Adam Plunkett wrestles with how to fit the mercurial work (no American poet shifts tones so suddenly or subtly as Frost) with the mercurial life.”

What happened to Europe’s farmers? Colm Tóibín reviews Patrick Joyce’s Remembering Peasants: “The statistics for the decline in people working on the land in Europe are stark. In Remembering Peasants, Patrick Joyce reports that in 1950 nearly half the population of Spain were agricultural workers. By 1980 the figure was 14.5 per cent; by 2020 it was less than 5 per cent. In France the proportion of people working in agriculture was 23 per cent in 1950 and 3 per cent in 2019. So much has changed in the last few decades. ‘The EU,’ Joyce writes, ‘lost 37 per cent of its farms between 2005 and 2020, almost all of which were tiny holdings, less than five hectares.’ Many of those who came from the land went to work in factories and in retail. The town of Westport in County Mayo is close to where Joyce’s father was born. ‘In the town,’ he writes, there is a factory that ‘produces the entire world’s production of Botox ... This is a world beyond the imagination of the parents and grandparents of those who work there, and one scarcely credible to me.’”

Alexander Larman writes about P.G. Wodehouse in America: “When the English writer and humorist P.G. “Plum” Wodehouse died 50 years ago this month, most would be forgiven for believing that his death took place at some grand English country house, not unlike Blandings Castle, or some salubrious Mayfair gentleman’s flat of a kind that Bertie Wooster inhabited. It therefore comes as a surprise, even a faint shock, to discover that Wodehouse died at his home in Southampton, New York, aged 93. And it might provoke a far greater shock to realize he had lived in the United States for nearly 30 years previously. He visited Britain for the final time in the summer of 1939 and never returned there again, because he was terrified of being arrested and imprisoned after some ill-advised broadcasts that he made during World War II, on behalf of the German authorities, went down predictably badly in his home country. To this day, a stigma hangs over his name in Britain because of them.”

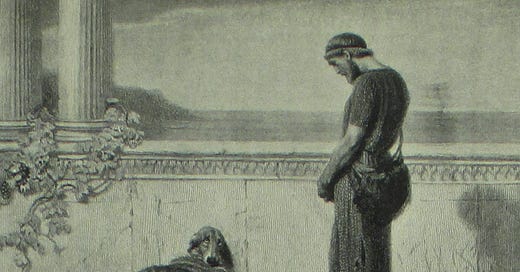

Homer’s dogs: “From the opening invocation onward, the Iliad mentions hundreds of dogs, with over eighty variations upon kuōn, almost always in the plural, among other canine terms. And yet these multitudinous dogs play an oddly minor role in the epic. While dogs are frequently mentioned, they are seldom actually seen. They develop no individuality, display no personality, exert no real presence. They are found in formulaic phrases, often paired, either negatively with carrion birds, or more positively (though sometimes it is hard to tell) with human beings. They often figure in similes, but usually as a secondary supporting element, and in terser metaphors, invariably pejorative. They do haunt, though only vaguely, the minds and fears of warriors, including Hektor and Akhilleus, and finally of Priam. But these dogs never actually do anything. Amid so many Homeric animals—dynamic battle horses, birds both scavenging and auguring, lions and boars starring in similes and metaphors, oxen sacrificed in culture-confirming ceremony and eaten with real hunger—dogs play a relatively minor role in the Iliad . . . The Odyssey turns from all this. It has barely a tenth of the horses of the Iliad, and 60% of those are found in Books 3, 4 and 15, which first narrate and then recount Telemakhos’ experiences in Pylos and Sparta. The reduced presence of horses makes perfect sense for an epic set at sea or on the narrow island of Ithaka. As Telemakhos artfully declines Menelaos’ gift of horses . . . the Odyssey itself turns away from horses. Dogs, less grand, more agile, well suited to both a rocky island and a family romance, expand to fill the spaces vacated by Homeric horses.”

Damian Thompson reviews Yvonnick Denoël’s Vatican Spies: “By definition, secret agents are supposed to be difficult to identify. It’s doubly hard in the case of the Vatican spies who are the subject of the French historian Yvonnick Denoël’s book because so many of them have been priests. Those employed by the Church range from taciturn creatures of the Curia — George Smileys in clerical collars — to heroic clergy who take insane risks behind the lines in order to help persecuted Catholics.”

Poem: Gretchen Bartels-Ray, “Birds of the Air”

Revisiting the work—and method—of Marion Milner: “The psychoanalyst Marion Milner was born with the 20th century. She was the youngest child of a middling-posh family: meadow at the bottom of the Surrey garden, nannies, ponies, boarding school, a stint training as a Montessori teacher and in 1924 the award of a first-class degree in psychology from University College London. She was 26 in December 1926 when, feeling obscurely dissatisfied with her life, she decided to keep a diary in which she tried to establish ‘a method for discovering one’s true likes and dislikes’ by noting down ‘what kinds of experience made me happy’ . . . It was a scientific experiment. Her conclusions were to be based on the observation of facts, even if those facts turned out to have the character of feelings. At the time Milner was gathering information on industrial productivity in her day job as a psychologist with Cyril Burt (famous for his research on hereditary IQ). She was perfectly at home with the idea that human behaviour could be analysed systematically, and particularly interested in the application of Piaget’s ideas about child learning and development to industrial psychology. In 1927 she got herself transferred for a year to Harvard Business School, to work with Elton Mayo on the Hawthorne experiments into workplace productivity . . . The Milner method is attractive because it is rooted in everyday and amateur practices of reading, writing, drawing and (maybe not quite so everyday) psychoanalysing, and yet promises transcendence. Milner is at ease dropping in references to Keats’s negative capability, Blake’s illustrations of the Book of Job, and the Satany bits of the Bible. She is happy to daydream and to doodle and to remind us that what we are doing when we find substitutes for things, like the absent mother, is seeking the familiar in the unfamiliar, as Wordsworth said the poets do.”

Speaking of the “amateur practices of reading, writing, and drawing,” the critic Jeffrey Bilbro explains why he writes and publishes “amateur verse”: “It’s been a strange experience to publish this little book of poems. In part, this is because I don’t consider myself a poet. The act of making poems doesn’t define my identity, and it’s certainly not how I make a living. But it is a small yet significant part of how I make a life. Over the years, I’ve found great value in, as my professor David Lyle Jeffrey puts it, committing random acts of poetry.”

Ágota Kristóf’s exiled fiction:

My maternal grandparents were born in the former Yugoslavia, a nation bloodily dissolved in 1991. I was one year old. A decade later, on Easter, I brought potica, a babka-like Slovenian pastry my mother always made on holidays, to my Indianapolis elementary school. “Hey,” I said. “Here’s some Yugoslavian holiday bread,” because that’s what my family still called the former Republic at home. Of course I’d chosen to bestow these gifts—potica, my ignorance—on my geography class. My teacher guided me to the newly minted map across the room.

Interrupted childhood—the shock of realpolitik as filtered through a child’s eyes—lies at the heart of Hungarian writer Ágota Kristóf’s work. Born in rural Hungary in 1934, Kristóf fled after the 1956 Uprising to Switzerland, where she remained until her death in 2011. Her stories and novels are set during unnamed wars in unnamed countries once known as something else, amid shifting borders and toppled regimes. They often feature children, who report these upheavals with brutal clarity. The ruthless twin boys at the center of The Notebook (1986) made her famous, and undoubtedly constitute one of the most powerful child perspectives in the European canon. When adults, her protagonists are forever searching for the nations, families, and cities in which they were born, or, as Kristóf wrote in her own autobiography, for those years before “the silver thread of childhood [was] severed.” It’s a doomed kind of search. For those who succeed, lost kinships and homes, once recovered, turn out to be mostly unrecognizable.

How refrigeration has changed the way we eat and live: “This semi-refrigerated way of life – which is common in middle-income countries – has long vanished from the UK, though many of us remember the warm-blood smell of the butcher’s shop, the sometimes rancid taste of butter, the cheesy aroma of bottles of school milk during break-time in summer. Do you recall the days in the 1980s when British ice-cream cones were rectangular rather than round, because the only way to fit ice cream into a tiny domestic freezer compartment was for it to be oblong-shaped, designed for slicing rather than scooping? These blocks – known unappetisingly as ‘cutting bricks’ – came in the standard flavours of the postwar decades: ‘Neapolitan’, synthetic ‘vanilla’ and so on . . . In Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet and Ourselves, Nicola Twilley argues that at each stage of its development, modern refrigeration has driven us to eat and behave in ways we wouldn’t have chosen if we could design the system from scratch. To take just one example, she explains that refrigeration is the main reason that so many commercial tomatoes are flavourless. It isn’t just that the volatile aromas in a ripe tomato are killed by the cold, or that the ripeness may be generated by ethylene rather than the sun, but that most of the tomatoes grown commercially don’t have the ‘genetic capacity’ to be delicious, as the plant breeder Harry Klee told Twilley. Tomatoes, she writes, are bred for ‘the sturdiness to be shipped and stored under refrigeration’. The important thing is that, at the moment of purchase, a consumer should deem the tomato red and perfect, even if it is left to spoil after it reaches the salad drawer at home.”

Christopher Caldwell reviews Angela Merkel’s memoirs: “German readers have a powerful appetite for doorstop political autobiographies, gossip-filled 600- and 700-page apologias by major statesman and even minor party hacks. Never has such a book been more eagerly awaited than that of Angela Merkel, chancellor of Germany from 2005 to 2021 and arguably the towering female officeholder of the modern age, with Margaret Thatcher and Indira Gandhi as her only competition. Never has such a book suffered from lousier timing, either.”

David J. Garrow reviews an excellent new history of the supreme court: “UCLA law professor Stuart Banner’s new book is simply the finest and most valuable book ever written about the U.S. Supreme Court, a work of such erudite breadth and interpretive sophistication that in a world governed by merit, it would be a slam-dunk winner of an upcoming Pulitzer Prize. Yet in today’s deeply degraded media landscape, only one major publication—the Wall Street Journal—has seen fit to give it the review attention it so richly deserves.”

Brooke Allen reviews a new collection of essays pulled from over 70 years of The Hudson Review:

When Frederick Morgan, Joseph Bennett, and William Arrowsmith launched their literary magazine The Hudson Review, they had a broad vision. They wanted to publish well-known authors they admired, particularly if their work was not aimed at the commercial market. They were also eager to publish new works by unknown writers as a service both to their readers and to the larger literary community. The Hudson Review has been strikingly successful in both departments: their very first issue, in the spring of 1948, included luminaries of the period like Wallace Stevens, Herbert Read, and R. P. Blackmur, but it also contained a story by the twenty-eight-year-old Alex Comfort, as well as the first published poem of W. S. Merwin, at that time only twenty. Very early works by James Merrill, Anthony Hecht, Louis Simpson, and Wendell Berry also appeared in the magazine’s pages.

The three editors had cut their teeth in the early 1940s at Princeton, working on the Nassau Literary Magazine, of which Morgan became the co-editor and Bennett the managing editor; Arrowsmith, two years younger, was also on the staff. Their ambition—audacity, even—can be measured from the fact that they obtained a piece from Thomas Mann for this college publication. Their mentor at Princeton, Allen Tate, encouraged their efforts and suggested that they start their own magazine after the war, during which both Morgan and Bennett served in the armed forces.

From the beginning the editors wanted The Hudson Review to have a strong critical component, as they wanted their bailiwick to move beyond literature to music, theater, dance, and the visual arts. Ezra Pound, who contributed to the newborn periodical and took a lively interest in it, addressed rather hectoring letters of advice from his room at St. Elizabeths Psychiatric Hospital in Washington, D.C. He advised them to drop the critical element, but Morgan defended the genre stoutly . . . Political ideology and dogma were abhorrent to all three men. And they sharply differentiated The Hudson Review from academic journals. “I suppose there are independent minds in the academy,” Morgan said, “just as there are everywhere, but they are scattered around.” The magazine would publish the work of many professors and lecturers, but not those who wrote for a specialized readership.

Django Ellenhorn writes about men and fiction:

Writing anything about the woes of young men in contemporary fiction can feel like yammering about a lost cause. It can also prompt some pretty fatuous counters. Not even Joyce Carol Oates could be spared — when she shot out a tweet in 2022 about how a literary agent had told her he couldn’t even get editors to look at debuts by ambitious boys, the Twitterati collectively told her to get stuffed. So, here’s what this is not:

I’m not saying that literary culture has degraded because women pack the book world to the brim; I’m not saying that Stephen King and James Patterson are immaterial nobodies, that their sales numbers matter not at all; I’m not saying that nonwhite folk have a cinch of a time getting their books on the shelves; and I’m not saying that female editors should now be freighted with the grim responsibility of victors and must dole out ginormous contracts to yearning and pitiful mediocrities just because they happen to be male. Everyone knows that some of the writers crying foul about the paucity of men getting published are mere aggrieved nimrods trapped in a deserved eternity of irrelevance. The phallus is no skeleton key for unlocking the mystery of their nothingness. They just suck.

But those are just some of the men who remain. Most of them are gone. In the cramped world of literary fiction, it can pay to be reductive, so I’ll do the same: young men don’t read and young men don’t write, and if they don’t read then they won’t write, which probably won’t matter, because right now candid depictions of male reality have little place in books. To a certain type of person, even our thoughts feel like a species of threat. And that’s no fun.

Read the whole thing, though I am not convinced that “young men don’t read and young men don’t write.”

Forthcoming: Joshua Hammer, The Mesopotamian Riddle: An Archaeologist, a Soldier, a Clergyman, and the Race to Decipher the World's Oldest Writing (Simon & Schuster, March 18): “A rollicking adventure starring three free-spirited Victorians on a twenty-year quest to decipher cuneiform, the oldest writing in the world—from the New York Times bestselling author of The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu.”

Oh my goodness! Thank you not for the link to the essay in the Metropolitan Review. Not because I’m incurious about the “men don’t read or write” anymore. That’s the defining existential question for male writers at the moment and I’d love to be engaging you in that topic at the moment. However, the referred essay, while obviously well researched (far beyond what my stamina could bear) felt more like a sustained whine than the intellectually astute argument a new, striving, marquis piece a neonatal literary journal should be publishing. I’d love to be referred to a well conceived critique of contemporary women’s literature. We know women can write as well as men and create male and female characters as well as men (for me with my own limited experience I’d cite George Eliot, Wolf, and Hazard as examples and forgive me if I’ve misspelled, I’m old and it’s late!). I felt like the young author (and I’m afraid of losing what I’ve written if I leave to look up his name) is so angry at how far the pendulum has swung against the old paradigm that he’s wasted a vast amount of time reading women authors he hates instead of focusing on his own writing.

Okay. I got that off my chest. Hopefully tomorrow I’ll remember to go read about Homer and how he writes about our friends in the animal kingdom. I’m looking forward to that!