Saturday Links

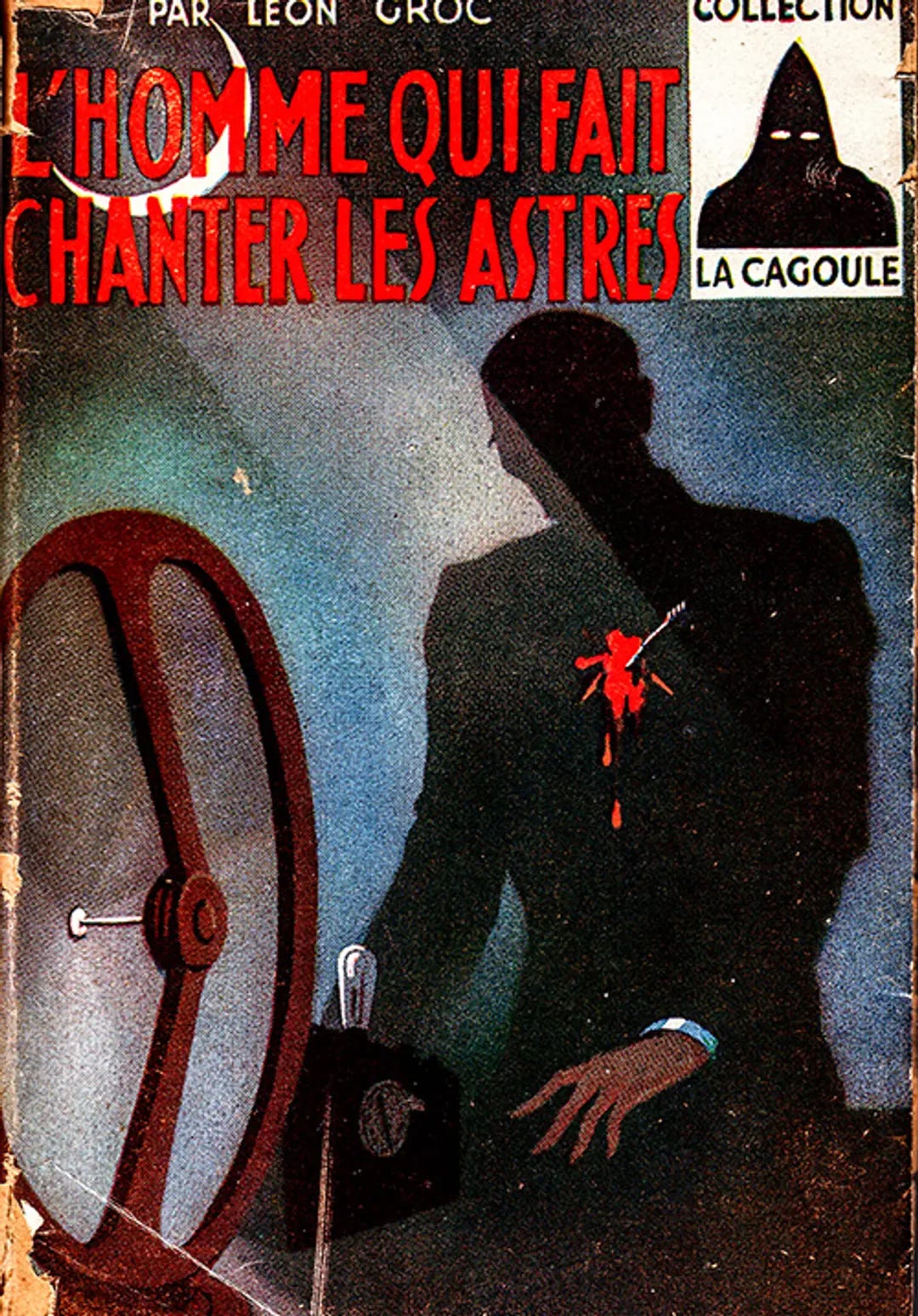

Ocean Vuong’s “ridiculous” prose, revisiting the “merveilleux-scientifique” novel, the reception of Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” Radiohead’s “Hamlet,” and more.

Good morning! Tom Crewe reads Ocean Vuong. “Something very strange has been going on,” he writes:

Picking up the paperback of Ocean Vuong’s first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, which has now sold more than a million copies, you encounter blurbs the likes of which you’ve never seen before. ‘A marvel,’ Marlon James says. Daisy Johnson tells us that ‘Vuong is rewriting what fiction is supposed to be’ and – forgetting the medium – that ‘it’s a privilege to watch.’ ‘Thank you, Ocean Vuong,’ Michael Cunningham chimes, ‘for this brilliant and remarkable first novel.’ Ben Lerner goes big: ‘Vuong ... expands our sense of what literature can make visible, thinkable, felt across borders and generations and genres.’ He must have thought this would be hard to beat. But he hadn’t reckoned on Max Porter, who declares it ‘a masterpiece ... a staggeringly beautiful book’, and what’s more, a ‘huge gift to the world’.”

“Then you read the book,” he writes, and discover it is not very good . . . at all. More:

Vuong is also a poet. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous came out three years after his first collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds, which won the T.S. Eliot Prize, among others. Vuong considered himself to be reworking the traditional novel in a poetic vein (in interviews he overestimates the novelty of this attempt, and tends to speak as though modernism didn’t happen). What this actually means, since the form of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is conventional, give or take a few line breaks, is that the book is written in an extremely elevated register. This would be fine if well handled, but what strikes you at once about Vuong’s prose is its bludgeoning inexactness – not a fruitful, poetic ambivalence, but sheer clumsiness. Tenses slip: ‘We didn’t know everything yet ... when we grow up, we’d know how the world really works’; ‘There are times, late at night, when your son would wake believing a bullet is lodged inside him.’ Constructions are off: ‘The milk poured with a thick white braid’; ‘Some things are so gauzed behind layers of syntax and semantics’; ‘Who put my hands in my face?’; ‘Because I am your son, what I know of work I know equally of loss. And what I know of both I know of your hands.’ Descriptions frequently make no sense: a monkey has its brain scooped out of its skull, but Vuong refers to its ‘hollowed mind’; ants are ‘fractals of a timeworn alphabet’; a helicopter ‘dismembers’ air; a field of tobacco will ‘green itself to the height of a small army’; lawns are ‘suicidally pristine’; ‘You stared at the two holes in my face’ – by which he means eyes. Images are confused: ‘This is an old story, one anyone can tell. A trope in a movie you can walk away from, if it weren’t already here, written down’; ‘I ... saw the coiled summer air, sputtering with heat, rise over the razed fields.’

Vuong has a genius for the simile or image that baffles, that is in essence a non-sequitur, or series of non-sequiturs: ‘About seventy ... with mined-out blue eyes, she has the stare of someone who had gone beyond where she needed to go but kept walking anyway . . . The crows floated over the field’s wrinkled air ... their shadows swooping over the land like things falling from the sky . . . The liquid coming down in white strings like a tablecloth in a nightmare . . . Blood so red, so everywhere, it was Christmas in June . . . There was something about the way he looked when lost in thought, his brow pinched under squinted eyes, giving his boyish face the harsh, hurt expression of someone watching his favourite dog being put down too soon . . . I wanted the word to fall, like a screw in a guillotine.’

If this wasn’t enough, the book is intolerably busy with vatic, empty utterances of this sort: ‘Who will be lost in ourselves? A story, after all, is a kind of swallowing. To open a mouth, in speech, is to leave only the bones, which remain untold . . . What if the body, at its best, is only a longing for a body? . . . It is no accident, Ma, that the comma resembles a foetus – that curve of continuation. We were all once inside our mothers, saying, with our entire curved and silent selves, more, more, more . . . Isn’t that the saddest thing in the world, Ma? A comma forced to be a period? . . . I know. It’s not fair that the word laughter is trapped inside slaughter . . . Only when I utter the word do I realise that rose is also the past tense of rise. That in calling your name I am also telling you to get up. I say it as if it is the only answer to your question – as if a name is also a sound we can be found in. Where am I? Where am I? You’re Rose, Ma. You have risen.’

This language is not poetic, but ridiculous, sententious, blinded by self-love and pirouetting over a chasm.

Crewe also reads Vuong’s new novel, The Emperor of Gladness. It is even worse.

I review Alan Jacobs’s new book on Paradise Lost:

Is there a book more widely loved than Paradise Lost by an author more universally disliked than John Milton? Catholics dislike Milton for his anti-Catholicism, Anglicans dislike him for his nonconformity, monarchs dislike him for his republicanism, republicans dislike him for his religiosity, and feminists dislike him for his supposed misogyny. Samuel Johnson captured the sentiment of many in saying that Milton’s “predominant desire was to destroy.” But Paradise Lost? Johnson writes that it is, “A poem which, considered with respect to design, may claim the first place … among the productions of the human mind.”

In his “biography” of Paradise Lost, which is part of Princeton University Press’s excellent Lives of Great Religious Books series, Alan Jacobs traces Johnson’s and others’ responses to Milton and his most famous poem. Jacobs gives special attention to two that are especially long-standing: that Paradise Lost shows Milton’s special hatred of women, and that [it shows] Milton’s hatred of authority. The first, Jacobs argues, is an oversimplification. The second, which usually goes hand-in-hand with the view that Satan is the real hero of the poem, is simply wrong.

Dominic Green reviews a new biography of Stefan Zweig in The Wall Street Journal: “Stefan Zweig was probably the world’s most famous living Austrian before the rise of Adolf Hitler. Among the most widely translated authors of the 1920s and ’30s, Zweig specialized in novellas of doomed romance whose titles sound like prompts for a Freudian case study (‘Fear,’ ‘Compulsion,’ ‘Confusion’) and biographies that insert the speculations of psychoanalysis into the shell of heroic lives (‘Montaigne,’ ‘Balzac,’ ‘Amerigo’) . . . Rüdiger Görner’s ‘In the Future of Yesterday: A Life of Stefan Zweig’ is an elegant and compassionate look at the contrasts, aspirations and disasters of its subject’s age. Its message resounds loudly in our own time, when, as Robert D. Kaplan observes in ‘Waste Land,’ published this year, the breakdown of the American-led global system resembles the fate of the Weimar Republic.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Prufrock to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.