Saturday Links

Andrew Young’s weird long poem, the rise of the concert, in defense of audiobooks, revisiting Evelyn Waugh’s “grossly over-stylized” novel, the return of “Lapham’s Quarterly,” and more.

Good morning! The New Criterion’s annual poetry issue is out. Adam Kirsch was kind enough to ask me to contribute something, so I wrote about Andrew Young’s weird long poem about time, space, and the afterlife:

Most of Young’s work is “compact like a kernel.” At the time of Allott’s review, Young was known—to the degree that he was known—for his sometimes dark and always compressed nature poems in which sharp contrast and paradox produce the primary effects. These are the poems of Winter Harvest (1933), The White Blackbird (1935), and Selected Poems (1936), which included a significant number of revised poems from eight small-run editions (published under the name “A. J. Young”) that were unknown even to many of the so-called cognoscenti . . . In 1953, Richard Lawrence, who later edited a collection of essays on Young’s poetry, described Young’s verse as “Terse” and “highly-charged”: “No poet has made a word work harder for its living than Andrew Young. . . . Yet such is his art, one never feels that the idea enshrined in a given lyric has been anything but completely expressed; it is merely that no one single unnecessary word has been used—there are no trimmings, no grace-notes.”

Yet, towards the end of his life, he wrote a long poem in two parts about the soul of a man stuck between this life and the next:

The first part, Into Hades, was completed in 1952, and the second part, A Traveller in Time, was completed in 1958. Young dedicated Out of the World and Back to his wife and wrote the following in the preface: “When the spring of short Nature poems ran dry, I was not altogether sorry, for while my interest in Nature was intense, it was not as deep as the underlying interest that prompted me to change my style and write Into Hades.”

The poem is written in very loose blank verse—a stark contrast with Young’s formal nature poems. The “underlying interest” that Young refers to here is the afterlife.

Why a poem about the afterlife might require, in Young’s mind, a looser rather than tighter structure than his nature poems is not immediately clear. The poem is obviously modeled on Dante’s Divine Comedy—a poem that is structured by intricately interlocking terza rima . . . Yet . . . it is more plausible to understand the differences between the two poems as a result of their differing subject matters, however similar they appear. In the end, Young’s poem is about the soul being reborn at the Resurrection, while Dante’s Divine Comedy is about the progress of the soul here on Earth depicted symbolically as a walk from Hell to Heaven.

The “peculiar” situation Young attempts to capture imaginatively in Into Hades is the experience of being outside time and between two worlds—this one and the next one—in verse, which is quite different from Dante’s.

Read the whole thing if you’re interested. Young was also a strange man, as I note in the review. Here’s a snippet:

He was no poète maudit, but he certainly battled minor demons. Here was a man who would sit at a separate table from his family at every meal and read the paper rather than participate (at least directly) in the evening’s conversation. He expected his wife, Janet, to wait on him hand and foot. When she was late serving him tea in his office, he once threw the kettle down the stairs to express his displeasure. As a minister, he made long walks to visit his parishioners but would sit in silence once he arrived. He would gladly take tea, sherry, or whisky if offered, but he wouldn’t make conversation. Sometimes he fell asleep. His silence was so unnerving that one parishioner gave him a book to read. He read the whole thing, stood up, gave it back to her, and left. When he would have writers to his house for an evening discussion, he offered only mints and whisky.

He was prone to angry outbursts if things did not go his way. When he was told that he was not allowed to swim in a lake he was visiting, he told the attendant: “Then I’ll take off my clothes and swim in your face!” Yet he doted on his grandchildren, and when Janet had a stroke and became unable to care for the house and her husband, Young took everything on himself and cared for his wife (though with less patience and goodwill) as she had cared for him his whole life.

Also in The New Criterion, Brenda Wineapple writes about Robert Frost, Gary Saul Morson reviews a new book on Czesław Miłosz, and William Logan writes about Ezra Pound’s time in Rapallo.

Katherine Powers writes in defense of listening to audio books in The Washington Post: “Although audiobooks are the fastest growing segment of publishing, there are still plenty of people who believe that listening to a book is somehow low and lazy, that, put baldly, it’s cheating. I suppose this attitude springs from the ‘work ethic’ in which we Americans are said to believe. In this view, reading is virtuous in the same way that working is — while listening amounts to some kind of handout. But is listening to a book cheating? . . . Disparaging audiobooks often springs from the feeling that a listener can’t take in a book as fully as a reader can. Neuroscientists have, of course, weighed in on the subject. The conclusion reached in the arduously titled 2019 study ‘The Representation of Semantic Information Across Human Cerebral Cortex During Listening Versus Reading is Invariant to Stimulus Modality’ from the Journal of Neuroscience is, in a nutshell, that we understand words whether they are read or heard.”

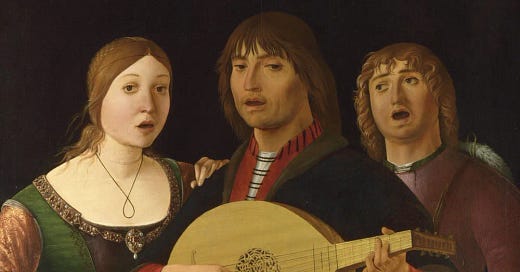

The rise of the concert: “A recorder and a bow carefully balanced across the neck of a rebec. A stone parapet. Three singers, two of whom beat time, fingers tapping on the ledge, while a central shaggy-haired singer plays the lute, his eyes downcast as he reads from an open score. The man on the right looks to the lutenist, but the woman on the left looks out beyond the parapet, engaging the viewer with a direct gaze. She is richly dressed with jewels at her neck and a delicately woven hairnet, with one hand resting on the lutenist’s shoulder. This painting in the National Gallery by Lorenzo Costa is today known as A Concert (c. 1488–90), but this scene does not record a public performance as such. Rather, it commemorates the rise of a new pursuit at the courts of Renaissance Italy in the last decades of the 15th century: cantare al libro, or sight-singing from a book. Indeed, while its subject has notable precedents in earlier relief sculpture by Luca della Robbia, the painting is generally recognised as the earliest example of a new genre of ‘concert’ paintings that emerged in northern Italy – particularly the Veneto – in tandem with the increasing popularity of this leisure activity.”

Poem: J. C. Scharl, “Honeymoon Road Signs on I-10 East in Arizona”

Harper’s has published an excerpt of Charles Portis’s unfinished novel The Woman from Nowhere. Read it here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Prufrock to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.