Reading the Booker Shortlist

Also: Picasso’s poetry, in defense of peasantry, the return of an 11th-century pipe organ, the first review of Thomas Pynchon’s “Shadow Ticket,” and more.

The novelist and critic Adam Roberts has been reading through this year’s Booker Prize longlist. Meanwhile, the six novels that made the shortlist have been announced. He’s read five of them: Only two “deserve to be shortlisted.”

Here he is on Susan Choi’s Flashlight:

No critic wants to be the Emperor Joseph II telling Mozart that Die Entführung aus dem Serail has ‘too many notes’. Foolish man, rich entitled buffoon standing before a for-the-ages genius: ‘too many notes, my dear Mozart.’ ‘It has,’ Mozart is supposed to have replied, ‘just as many notes as are required, no more, no fewer.’ Sick burn, Wolfgang!

And yet, here we are. Reading Susan Choi’s Flashlight, I found myself channeling Joseph-Zwei. This novel has too many words.

And on Katie Kitamura’s Audition, he notes that her writing is “routinely described as ‘beautiful’, ‘luminous’ and so on. But I found the prose to be, well, bad throughout”:

It is a mixture of banality (simple declarative stuff, a fair bit of cliché, ‘the shoe was on the other foot’ and so on) and complexity, fond of fancy words and Jamesian circumlocutions, or at least attempts at Jamesian subtlety. The prose is not very well done, in a nuts-and-bolts sense. Sentences are tautological, repetitive, read as if no editor has touched or improved them. Towards the end of the book the narrator says: ‘I was holding the stem of my wineglass by my fingers’. The final three words here are redundant and should be cut (how else is she going to be holding the stem of her wine-glass? By her toes?) The prose is like that all the way through.

This may strike you as me being picky, or overly pedantic. But I was repeatedly bounced out of the story by the slackness and stumblingness of its expression. Kitamura is a big star in contemporary writing, widely praised, award-garlanded and as here, Booker longlisted: we can expect better of her actual writing.

Read the rest of his posts and subscribe to his Substack, which is always worth reading.

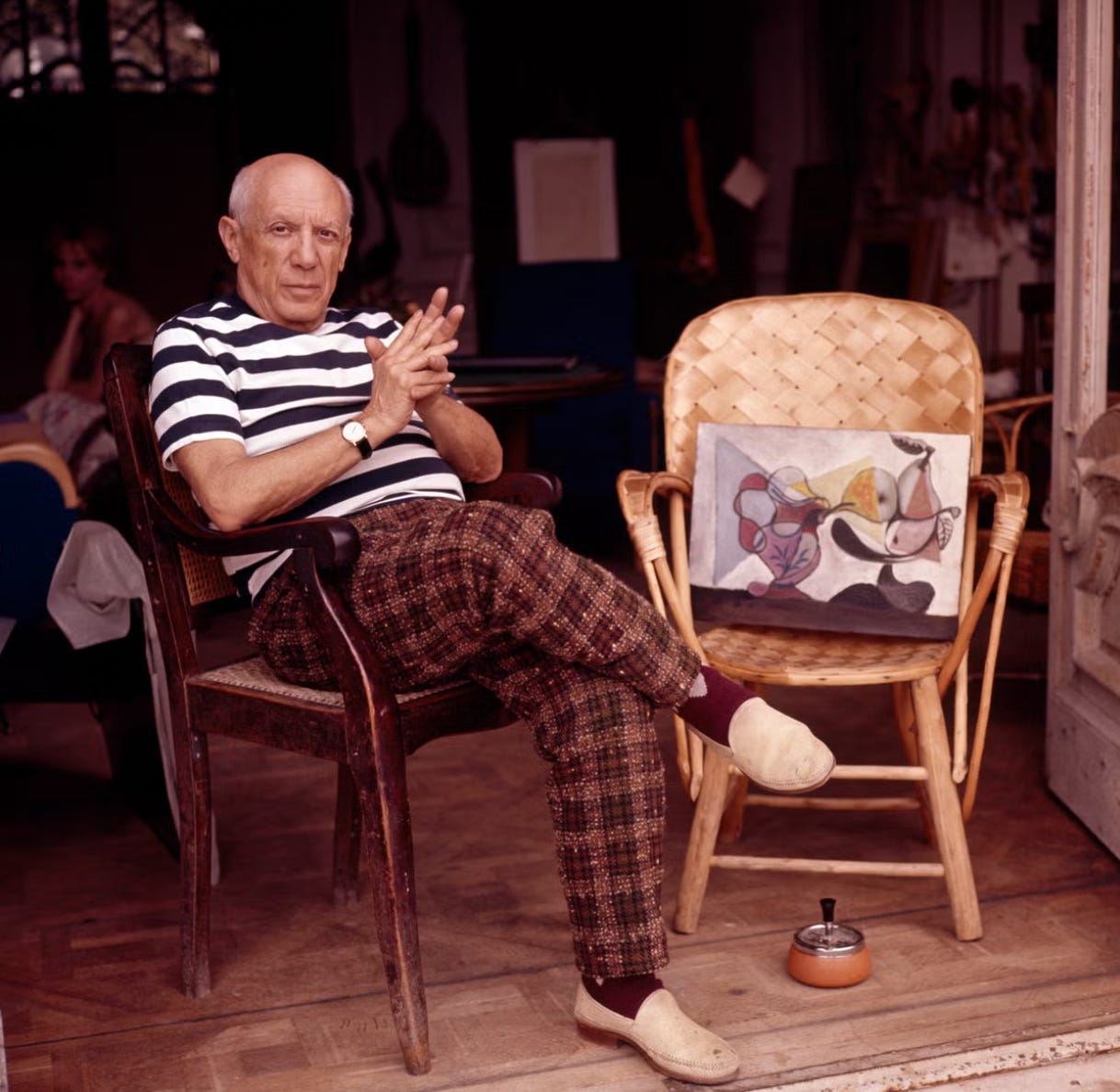

Did you know that Pablo Picasso wrote poetry? Andre Breton said reading it was like “being in the presence of an intimate journal . . . such as has never been kept before.” Gertrude Stein had a different take: “You see I said continuing to Pablo you can’t stand looking at Jean Cocteau’s drawings, it does something to you, they are more offensive than drawings that are just bad drawings now that’s the way with your poetry it is more offensive than just bad poetry I do not know why but it just is”

Here’s a snippet:

the street be full of stars

and the prisoners eat doves

and the doves eat cheese

and the cheese eat words

and the words eat bridges

and the bridges eat looks

and the looks eat cups full of kisses in the orchata

I’m with Stein.

Is everything terrible all the time? No. Here is Louise Marburg in The Hudson Review praising five works of fiction—three novels and two collections of short stories—from independent publishers: “Independent publishers are doing God’s work by giving voice to gifted but overlooked authors, and I’m delighted to be privileged to shine a light on a few.”

The world’s oldest pipe organ is back, and it sounds lovely:

Composed of original pipes from the 11th century, the instrument emitted a full, hearty sound as musician David Catalunya played a liturgical chant called Benedicamus Domino Flos Filius. The swell of music inside Saint Saviour’s Monastery mingled with church bells tolling in the distance.

Before unveiling the instrument Monday, Catalunya told a news conference that attendees were witnessing a grand development in the history of music. “This organ was buried with the hope that one day it would play again,” he said. “And the day has arrived, nearly eight centuries later.”

Peasants are defined by family farms, usually 10 acres or less, whose output is optimised both for subsistence and for cash income. The work is carried out primarily by (unpaid) family labour. Far more than farmers in rich countries – many of whom are effectively state employees – peasants are entirely exposed to the fluctuations of climate and markets; their fortunes can vary greatly from one year to the next.

Peasants are fully integrated with the 21st-century economy, which could not operate without their production of sugar, cotton, cocoa and other essential commodities. Although they control less than one-quarter of the world’s agricultural land, peasant farming is highly efficient, and estimates suggest 70 per cent of the world’s population depends on them for some or all of their food.

“We live like royalty and don’t know it,” Charles C. Mann introduces a new essay series on contemporary life at The New Atlantis:

At the rehearsal dinner I began thinking about Thomas Jefferson’s ink. My wife and I were at a fancy destination wedding on a faraway island in the Pacific Northwest. Around us were musicians, catered food, a full bar, and chandeliers, all set against a superb ocean sunset. Not for the first time, I was thinking about how amazing it is that relatively ordinary middle-class Americans could afford such events — on special occasions, at least.

My wife and I were at a tableful of smart, well-educated twenty-somethings — friends of the bride and groom. The wedding, with all its hope and aspiration, had put them in mind of the future. As young people should, they wanted to help make that future bright. There was so much to do! They wanted the hungry to be fed, the thirsty to have water, the poor to have light, the sick to be well.

But when I mentioned how remarkable it was that a hundred-plus people could parachute into a remote, unfamiliar place and eat a gourmet meal untroubled by fears for their health and comfort, they were surprised. The heroic systems required to bring all the elements of their dinner to these tables by the sea were invisible to them. Despite their fine education, they knew little about the mechanisms of today’s food, water, energy, and public-health systems. They wanted a better world, but they didn’t know how this one worked.

What is research? What is science? What does it mean to say that scientific research has discovered something new, or proven something long hypothesized? What is “scientific consensus,” and how much confidence should we place in it? Are scientific researchers motivated to push knowledge forward in whatever direction it may take? Or are they responding to very different incentives?

Terms like “science,” “research,” “discover,” and “proof” are rampant in everyday use. They play an enormous role in guiding both individual decision-making and public policy. Yet we rarely pause to consider what they mean and how we use them.

Graham Elliott reviews Michel Wieviorka’s new book on Jewish jokes:

Here’s one. A Jewish gentleman crossing a busy road is hit by a car. As he is lifted onto the stretcher, the ambulance man asks, “Are you comfortable?” He shrugs, winces and replies, “I make a living.” If that tickles your fancy for a melafefon, you should unscrew the lid and dip in.

What’s special about these jokes? The author Michel Wieviorka, of Polish-Jewish descent, sets down three strictures: they may only be created by Jews; only a Jew may tell them; the jokes must not be anti-Semitic (he drops the second of these early on in the book). The subject matter typically includes marriage, the materfamilias, money, death and traditional livelihoods — e.g. tailoring, the synagogue, the deli.

In praise of Rachel Ruysch: “Three of Rachel Ruysch’s paintings feature pineapples. In Still Life of Exotic Flowers on a Marble Ledge (c.1735), the fruit is hidden in a chaotic mass of stems and blooms, easy to miss behind an immense white flower head. In A Still Life with Devil’s Trumpet Flowers, Peonies, Hibiscus, Passion Flowers and Other Plants in a Brown Stoneware Vase (1700), you can see it clearly in the centre of the bouquet, its dark green leaves lit up and framed like a halo by the addition of a curved stalk at either side. You have to look twice to realise it’s floating in mid-air, supported by nothing sturdier than the stems and heads of the flowers beneath. Ruysch’s pyramidal bouquets often require some suspension of disbelief. The vases never seem large enough for the splendid, voluminous arrangements that loom over them. But a balancing act composed of flowers – lightweight, long-stemmed, delicate – is one thing; putting a pineapple in there is another. How would the fruit not topple the whole thing over? What would happen to the fragile-looking butterfly circling the base? Ruysch was a meticulous observer of nature, an artist whose insects seem real enough to buzz out of their frames. But her most innovative compositions have an unlikely aspect, a touch of the improbability that comes from throwing lilies and cabbage roses together with fruit from halfway around the world.”

The first review of Thomas Pynchon’s Shadow Ticket is in, and it is a big thumbs down. Here is Kathryn Schulz in The New Yorker:

Your appetite might differ, but for me, nine novels in, all this code-cracking and jigsaw-puzzling is no longer thrilling. The same goes for the other bells and whistles of Pynchon’s style; even a seventy-million-trick pony is still a trick pony, and much of what once seemed clever in his canon now seems tiresome. You will find, in “Shadow Ticket,” countless texts within the text, including the usual LP’s worth of songs—“Midnight in Milwaukee,” “Bye-Bye to Budapest.” (“Boo, hoo, hooo-dapest,” the singer croons.) You will find golems. You will find ghosts. You will find, if you bother to investigate, real-life oddities poached from the past because they come across like pure Pynchon invention—among them Clara Rockmore, a famous theremin player (Pynchon presumably appreciates her name), and a shoe-store X-ray machine for superior fittings, which not only really existed but really was produced by a Milwaukee company. You will find the aforementioned weird forms of transportation: that appropriated U-boat, an autogiro, an enormous motorcycle built to accommodate three German sleight-of-hand artists—Schnucki, Dieter, and Heinz, who collectively sound like a Minnesota personal-injury firm. And you will find, inevitably, characters with stranger names: Dr. Swampscott Vobe, Assistant Special Agent in Charge T. P. O’Grizbee, the noted illusionist or possibly genuine article Zoltán von Kiss. (As for our nomenclaturally modest hero, Hicks McTaggart, he is presumably named for J. M. E. McTaggart, an influential British philosopher who espoused the quasi-Pynchonesque beliefs that time is an illusion and that the human soul, connected to others of its kind by love, is the fundamental unit of reality.)

This one-man-band blare never quiets, but the music darkens considerably toward the end of “Shadow Ticket.” Jew hatred spreads and intensifies, Europe becomes a place to flee, and unrest over the price of milk in the United States results in a coup in which F.D.R. is toppled and General Douglas MacArthur seizes power. Stuck in exile, Hicks takes up with a motorcycle-riding Hungarian hottie but longs for Milwaukee, where the air smells like grilled bratwurst and sounds like accordion lessons and life “seldom gets more serious than somebody stole somebody’s fish.”

By then, I longed for Milwaukee, too—for the antic early pages of “Shadow Ticket,” when something coherent seemed to be forming beneath the fun. Instead, we get a darkness that is not just moral but epistemological. A suicide in a Budapest bathroom, a secret community of people sexually attracted to tasteless lamps, a movie plot entirely about violence and overeating: this stuff isn’t Bosch; it’s bosh—absurdity for absurdity’s sake, with no discernible aesthetic or intellectual purpose.

Wish I had the courage to dress like Picasso.

Thank you for the Charles C Mann article. Looking forward to the next installments!