Private and Public Art

Also: In praise of Antonio di Benedetto’s “The Suicides,” Zadie Smith’s multicultural fantasy, what dogs can teach us, and more.

A of couple of years ago, I started making cards for the birthdays of family and friends and for Christmas. I am no artist, so I cut images from various magazines to create what I hope is an odd but pleasing collage on the front of the card. I do it because I enjoy it. I also do it because it is a tangible way to show others I care about them. I try to make a card that is connected in some way to the person receiving it. Making cards takes time, and I hope each is a token, of sorts, of the time I would like to spend with someone else but can’t for one reason or another.

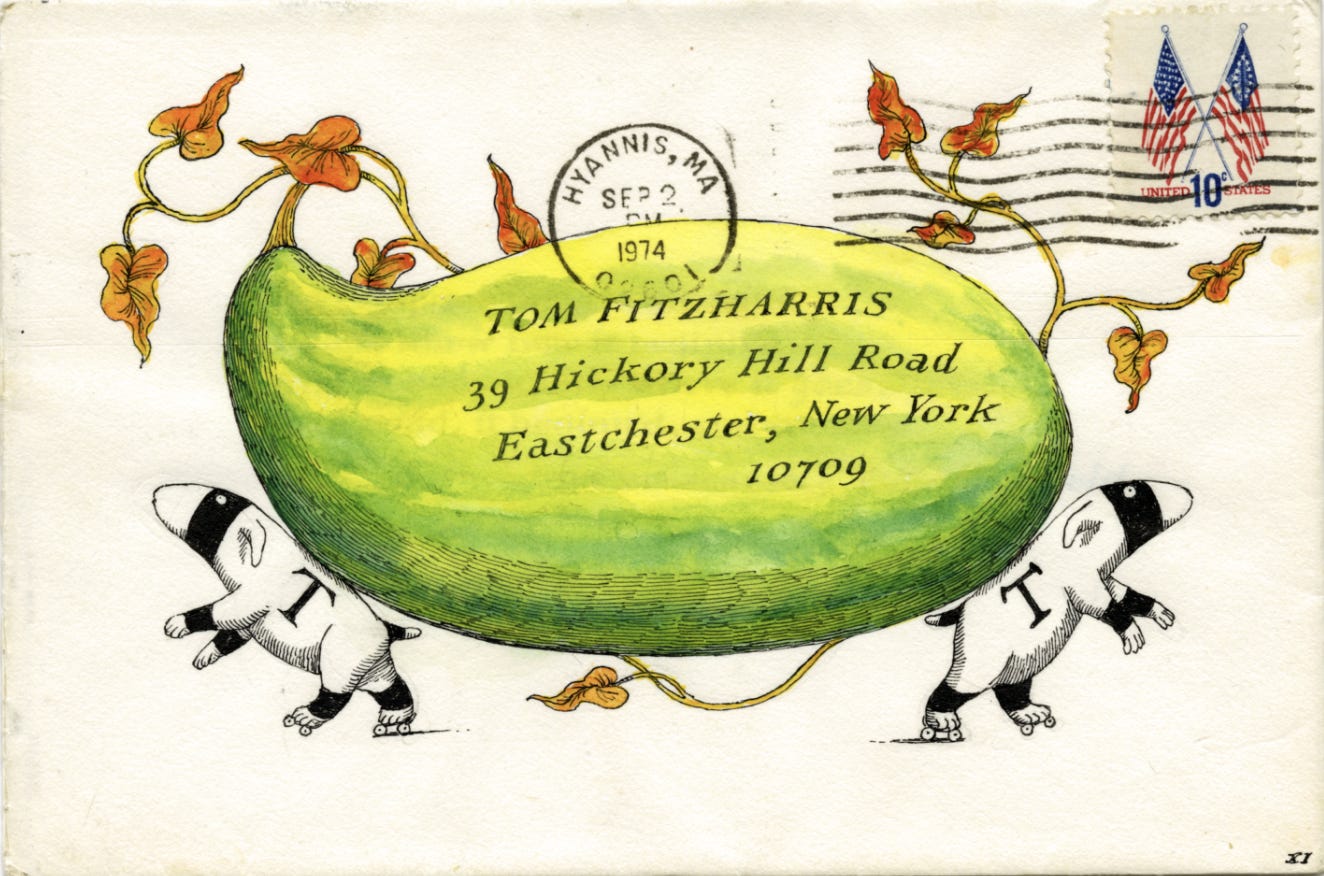

Edward Gorey—a real artist—sent over 50 illustrated envelopes and letters to Tom Fitzharris in the mid-1970s. Fitzharris kept them all. The New York Review of Books will publish them in February (both images of the envelopes and the letters). You can sneak a peek in the latest issue of The Paris Review, which includes this charming, short introduction:

Tom Fitzharris and Edward Gorey met one afternoon in 1974 when Fitzharris, long a fan of Gorey’s books and illustrations, bumped into him outside of the Town Hall, the performance space in Midtown Manhattan. Gorey—in his trademark fur coat, long beard, and sneakers—was immediately recognizable. The two struck up a brief but intense friendship. When Gorey was in New York, they met frequently, especially to go the ballet—Gorey planned his time in the city around the New York City Ballet’s performance schedule. His summers were spent in Cape Cod. It was in August of that year that Gorey began sending Fitzharris mail, richly illustrated both inside and out.

My cards will never be worthy of publication, but I do hope friends and family keep them.

Speaking of private art, Andrew Martin writes about a Warrington laborer who seemed to be “the most unaesthetic of men” living in “the most unaesthetic of places” but who produced some 500 high-quality paintings:

When Eric Tucker died, aged 86, in 2018, more than 500 paintings were found in the small council house he had long shared with his mother. The works, of the highest quality, depicted mid-20th-century working-class northern life. Many showed blurry, smoke-filled pub interiors, beautifully composed and full of slightly grotesque figures, typically side-on to show their strange profiles. They often look pale (except for red noses) and pensive, but they all have one another, and here is the first of many paradoxes about Eric Tucker.

He depicted scenes of sociability yet he himself was an uncommunicative loner with few close friends. But he had a sociable side. The young Joe was impressed by how he and Eric were once rescued from a rainstorm by a passing lorry driver who obviously knew his uncle. And Eric was warm and attentive toward Joe. “He’d school me in drawing, how to fill in a football coupon… what I could expect from a Ken Dodd live show. Long sermons on the latter.” Eric, who never married, was devoted to his mother, but he was not like some Alan Bennett character, emasculated by that connection. As a young man he’d had a boxing licence, and he remained a hard man in his attitudes. When, in his youth, Joe reported back on a Sunday school lesson about turning the other cheek, Eric, grasping his shoulders, counselled: “Joe, if someone hits you, you always hit them back.” With characteristic drollery, Joe Tucker observes, “In seconds, 45 minutes of gentle instilled Christian doctrine was overturned.”

Eric Tucker wasn’t totally secretive about his art. He had his painting room in the house, where he worked behind net curtains. Family members were not exactly barred from it, but they were not encouraged to enter, and he seldom went public with his work. He did a painting of a horse, which was displayed in the window of a Warrington bookies, until the council demanded its removal, because passing drivers were slowing to admire it. He had art books mingled in with his boxing magazines.

James Panero writes about Sabin Howard’s new World War I memorial in the latest issue of The New Criterion: “Howard’s most significant invention in A Soldier’s Journey was surely mothered by the necessities of his impending deadline and what he could fully do with the sculptural space that remained for him. For an artist who could spend years building up a single statue, a multipart relief of more than three dozen figures, all over life size, could quickly add up to a terminal Shrady sum. A manual artist, Howard turned to digital solutions . . . Technological advancements have always upended creative practice in both destructive and generative ways that can be long debated . . . For an artist long dedicated to the importance of manual craft, Howard’s digital intervention has created a hybrid sculpture. A Soldier’s Journey is not classical in its own right. It is rather a modern work that speaks to the classical tradition, quite literally, through a contemporary lens. Viewing the completed assembly soon after its unveiling last September—most revealingly in the stark spotlights that illuminate the monumental site at night and shimmer in its reflecting pools—I sensed I was experiencing not traditional sculpture at all but rather actors frozen on a stage. The uncanny-valley hyperrealism of Howard’s digital scans has left us with a cinematic diorama caked in plasteline mud. In memorializing a war that defied all convention and accelerated our modern era, this end result may ultimately be more successful than any purely classical relief.”

In The Baffler, Max Alper reviews Liz Pelly’s Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist: “For the first time, we have a single text that lays out, in exacting detail, the bullshit we’ve been fed and provides a thorough explanation as to how this Stockholm-based startup conquered the music industry and more importantly why.”

Listen to Victorians responding to Thomas Edison’s phonograph. Sir Arthur Sullivan: “I am astonished and somewhat terrified at the results of this evening’s experiments—astonished at the wonderful power you have developed, and terrified at the thought that so much hideous and bad music may be put on record forever.”

The BBC revisits its 1996 documentary of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, who survived Auschwitz because she could play the cello.

Tara Isabella Burton reviews Mark Rowlands’s The Word of Dog: What Our Canine Companions Can Teach Us About Living a Good Life: “‘Dogs are natural philosophers,’ Mr. Rowlands writes. They ‘know through living. And in the unbridled happiness of the dogs—in their love of life and their utter commitment to their actions … we can find answers to many of the traditional problems of philosophy.’”

Stuart Kelly praises Antonio di Benedetto’s The Suicides: “The Argentine writer Antonio di Benedetto was praised by Borges, Bolaño, Cortázar and Coetzee. He was born in 1922, on November 2, the Day of the Dead — which he made much of — and was imprisoned and tortured in 1976-77, during Argentina’s Dirty War. His eerie fables of paranoia, impending threat and incomprehension pre-empted his experience of them. Esther Allen deserves great credit for introducing the author to an Anglophone readership. Having read her translation of Benedetto’s Zama, followed by The Silentiary, I found the wait for The Suicides excruciating. But it was worth it. The final part of this ‘trilogy of expectation’ is, as it should be, a glorious anticlimax.”

Joseph Epstein reviews Josiah Osgood’s Lawless Republic: The Rise of Cicero and the Decline of Rome: “Osgood, a professor of classics at Georgetown University, recounts several of Cicero’s trials, including his first and last, and does so with quiet authority and impressive lucidity.”

In UnHerd, Ralph Leonard revisits Zadie Smith’s multicultural fantasy in White Teeth: “Mainly set in the ethnically diverse working-class area of Willesden, Smith’s multigenerational saga traces over 30 years the intertwined lives of three families: the Anglo-Jamaican Jones’, the Bengali Muslim Iqbals, and the secular Jewish Chafens. The novel mainly explores the ambiguities and anxieties of the immigrant experience, but what is particularly striking is the sanguineness throughout — a sense of possibility that seems quixotic in a post-Rochdale, post-BLM and post-Southport Britain. Even if it wasn’t wholly emblematic of contemporary Britain at the time, the book seemed to reflect what Britain could become. Reading White Teeth today feels like discovering an artefact of what the late social theorist Mark Fisher called a ‘lost future’.”

Tal Fortgang reviews Olivier Roy’s The Crisis of Culture: Identity Politics and the Empire of Norms: “The Crisis of Culture [is] a short but wide-ranging examination of what happens when old systems of norms disappear. Without a culture to provide the context and expectations for our interactions and judgments, everything needs to be stated explicitly, over and over again, to remain operative.”

In Holland, thieves blow up a door to steal a 2,500-year-old gold helmet and other artifacts: “The daring heist took place at Drents Museum in Assen during the early hours of Saturday morning, according to Dutch police, who said they received a report of an explosion at 3:45 a.m. local time. CCTV footage released by police shows the suspects opening an exterior door before a blast sends sparks and smoke into the air. The thieves made off with three gold bracelets, dating from around 50 BC, as well as the 5th-century BC Helmet of Cotofenesti, a historically important artifact on loan from the National History Museum of Romania in Bucharest.”

Loved this posting! In particular the article about Eric Tucker.