On Unsettling Literature

Also: Artistically disappointing lives, the work-home divide, boycotting Jewish writers, medieval minstrels, and more.

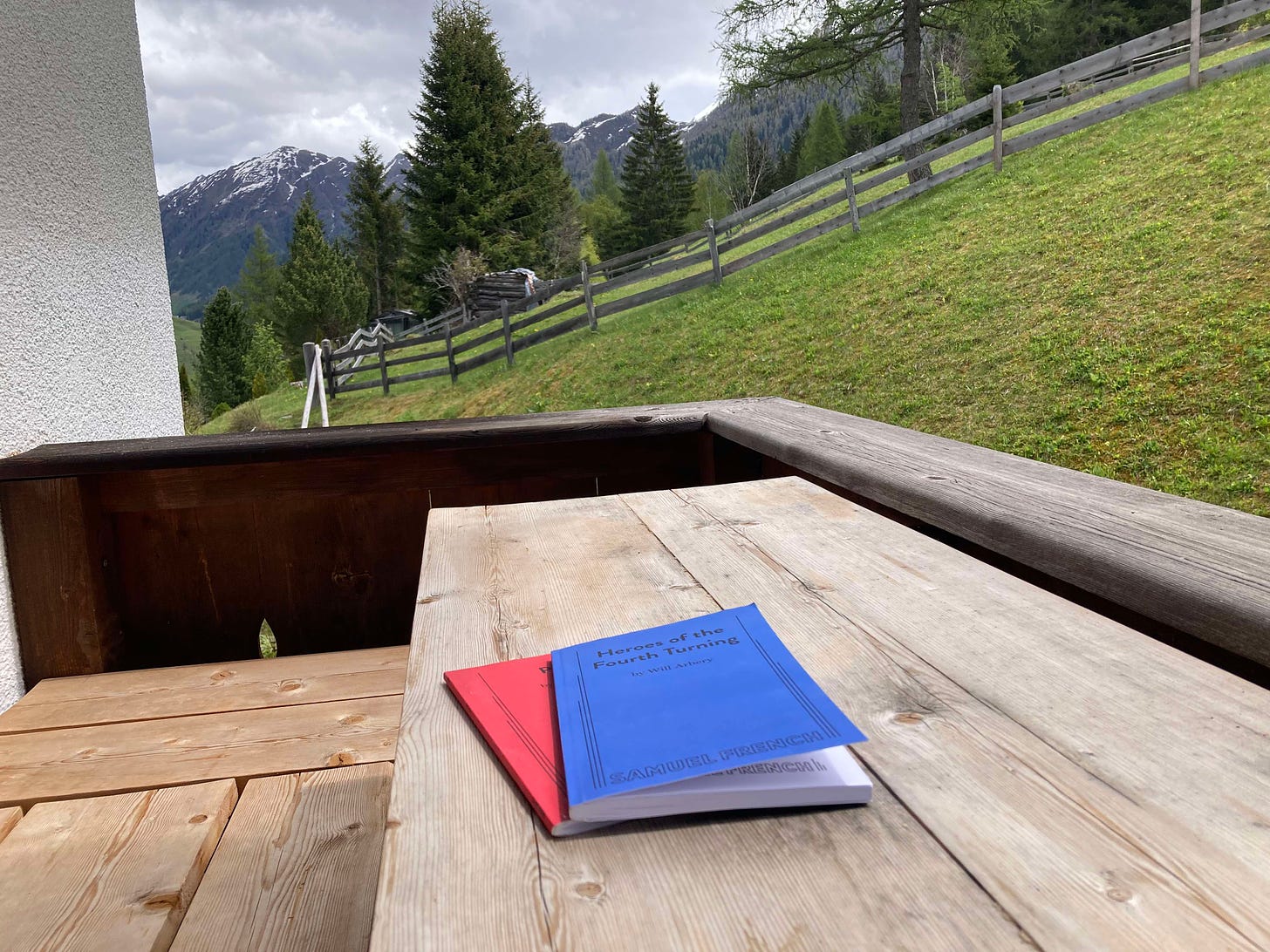

I have been meaning to read Will Arbery for a long time. When my wife and I were packing our bags for our summer trip to Europe, I threw Plano and Heroes of the Fourth Turning in my bag, as well as Randy Boyagoda’s Dante’s Indiana, Matthew Buckley Smith’s Dirge for an Imaginary World, all three collections of Toby Martinez de las Rivas’s poetry, and Alan Jacobs’s edition of Auden’s The Shield of Achilles, plus a bunch of books for the book project.

I devoured Dante’s Indiana on the flight over. It was neither as funny nor as unsettling as Original Prin, the first novel in the trilogy, but that isn’t a weakness. The book is trying to do something different from Prin—chart a return to personal order rather than an unravelling. I am much looking forward to the final book in the series, which Boyagoda has said is loosely based on Dante’s Divine Comedy and thus will finish in a sort of Paradiso.

It is difficult to write truly unsettling work. Books that are pitched as “shocking” or “transgressive” often fail to be either. The ordinary world the novel depicts may be so paper thin, so insubstantial, there is nothing to transgress. The authorial intention may be so obvious as to make the supposed shock entirely predictable. Rather than “complicating” our view of the world, these books confirm it, while also pandering to the us by presenting our view of the world as strangely original when it is, in fact, the most pedestrian of things. But it is even more difficult to write a work that is “re-settling”—that moves from disorder to order—without sacrificing complexity. It seems to me that this is what Boyagoda may be attempting to do.

Will Arbery, on the other hand, has written two truly unsettling plays in Plano and Heroes of the Fourth Turning. I read both—back-to-back—over three days, starting Plano in the small Swiss town of Chabrey and finishing it in the small Austrian town of Schmirn. I read Heroes of the Fourth Turning in one day in my daughter’s house.

Plano nearly made me physically ill. There is nothing violent in the book, but I think my own sense of disorientation from traveling was exacerbated by the play’s unrelentingly linguistic intensity set in a Texas where the rules of time and space no longer apply. The real world, quite frankly, started to float away, and I had to put the book down and go on a walk. My stomach feels a bit uneasy again just writing about it.

Heroes of the Fourth Turning is unsettling in a more customary way, as odd as that sounds. It is a book the gives us characters who are very ordinary and who possess a desperation or bitterness or fear that we also possess, but they possess it with unsettling intensity. The characters Arbery gives us in the play is a real accomplishment. They are no stereotypes, which is even more impressive since the play is very political—it’s about a group of conservative Catholic college friends who all attended a school in Wyoming that is clearly based on Wyoming Catholic College, where Arbery’s father, Glenn C. Arbery, served as president.

After reading just these two plays, which are stylistically very different, I am convinced that Arbery is one of our best contemporary playwrights, and I am much looking forward to reading his latest play, Corsicana.

But reading Heroes of the Fourth Turning also reminded me that even the best kind of unsettling literature (and literature is always unsettling to some degree—otherwise, there would be no plot) is always a confection, and this is a good thing to remember. The characters in Heroes are very realistic and, at the same time, very much anomalies—that is, abnormal, unreal, unlike most people.

This is to say that while literature reflects certain aspects of life by intensifying them, it remains an exaggeration, a lie. Of course, you might say, it tells the truth by lying, and I agree, but it doesn’t tell the whole truth. One thing literature does not tell the truth about is the very uneventful ordinariness of much of our everyday lives. To do so, it would have to be as long as life itself, and that, of course, is impossible.

Arbery himself recognizes this. In an interview for Paris Review on writing Corsicana, which is about his relationship with his older sister who has Down Syndrome, he said this:

At the time, I had just written Heroes, which was a draining and dark experience in a lot of ways. The idea of writing something that at least on its surface was a little bit gentler appealed to me. Then of course, once I’d written a draft, I started wondering, How do I complicate this?

“How do I complicate this?” What he means—in part, of course—is how does he make the play unreal, unlike his actual life.

I will be biking across part of Switzerland this weekend, so there will be no Saturday Prufrock. But I will be back next week with three full posts, plus John Wilson is working on his last fiction column before a brief break this summer. If you enjoy Prufrock, why not become a paid subscriber and support our work?

In other news, Alice Munro has died. She was 92. “Her stories are domestic, predominantly set in rural Ontario’s Huron County and populated with complex women reckoning with often disappointing circumstances. But within that familiar terrain, Munro could always tap new rich veins,” Megan Gibson writes in The New Statesman.

In the latest issue of The Hudson Review, Dana Gioia writes about the “artistically disappointing lives” of composers Gian Carlo Menotti and Carlisle Floyd: “Should opera composers write their own libretti? The advantages and disadvantages of single authorship are illustrated in the careers of two mid-twentieth-century American composers—Gian Carlo Menotti and Carlisle Floyd. The Italian-born Menotti and South Carolinian Floyd make an unlikely pair, but they share several unusual qualities. Both men wrote all of their own libretti. Both composed tonal music that ignored Modernist trends. Both achieved exceptional early success. They even shared longevity. Both men died at 95 after long, fortunate, and—this will be my subject—artistically disappointing lives.”

Also in The Hudson Review, which is chockfull of great writing, Victor Brombert remembers his childhood years in Leipzig during the late Weimar Republic and the example of his grandmother:

One evening, poetry and arias were brutally interrupted by a shattering sound coming from the street. We rushed to the window. Two cars had smashed into each other. The police soon arrived, and then an ambulance. In the partial darkness, we could distinguish a litter being carried. Some loud German voices reached us. Babushka ordered me back to the sofa, and she recited once again the early lines of Pushkin’s story of Onegin, about his wish that the Devil finally rid him of his uncle, too slow to die and leave him the long-expected inheritance.

That very evening, we were once again interrupted. This time by a marching group of SA stormtroopers vociferously singing the already famous “Horst-Wessel-Lied,” “Die Fahne hoch! . . .” (Raise the flag! The ranks tightly closed!), which soon became the anthem of the Nazi party. Babushka remained impassive. Had she not experienced far worse after the Revolution in Russia—when children were encouraged to denounce their parents, and when she and her husband were held prisoners of the Bolsheviks in their own villa’s servants’ quarters from which they were luckily saved by my father’s efforts?

Even though I had not yet reached my seventh birthday, I was aware of Babushka’s imperious character. She dictated to my mother what clothes to wear for what occasion, whom to invite and whom not to invite. But she also taught me a most important lesson. After she served my grandfather his daily scrambled eggs, I would frequently have lunch with her. My manners were still unpolished, and I would grab the food. Babushka then slapped my wrist and informed me that I must always ask first. Stubbornly naughty, I replied: “Yes, but what if I am alone?” Her own reply came swiftly. “Especially when you are alone.”

I understood, though the exact way of putting it evaded me. What she obviously meant was that under all circumstances it was a human obligation to maintain decorum, dignity, self-respect. One of her favorite French expressions was noblesse oblige. Years later, reading Primo Levi’s account of his Auschwitz experience, I recognized a Holocaust confirmation of the wisdom of Babushka’s repartee. When Levi’s group arrived in the extermination camp, a veteran inmate advised them above all to wash regularly, even in dirty water—not to please the guards or the SS, but to remain human beings, to maintain their humanity, to survive.

Jude Russo considers the relationship between Epicureanism and Christianity in The Lamp:

The structure of De Rerum Natura is, at its heart, very simple. Lucretius holds out the promise of Epicureanism, tranquility of mind; he explains the doctrines; he demonstrates the explanatory power of the doctrines with accounts of phenomena. The trend is to present the reader with more and more extreme and disturbing cases. The fifth book holds earthquakes and the end of the world; the sixth and final book concludes with a horrific description of the plague at Athens, the physiological particulars of individual deaths, perhaps of the reader’s individual death—the sort of death that he may face without disturbance if sufficiently tutored in the ways of the Master. It is a graded primer in what might be called the devout life.

Perhaps he was ahead of his time. Polite respect more than enthusiasm seems to have been the ancients’ definitive judgement on Lucretius. His style of poetry—grand, austere, always chasing Homer at its metaphoric heights, crabbed and involuted in the depths of technical doctrine—was on the way out in his own lifetime. The “neoterics,” or modernists, brought a Hellenistic flair to Latin letters; they replaced the polyphloesboean Homer with Callimachus and the nightingale . . . He must have had a partisan, though. De Rerum Natura survived from a single archetype copied at the court of Charlemagne around 800. This was proven by Karl Lachmann, that genius of almost legendary stature, who in 1850 used Lucretius for the first demonstration of modern stemmatic textual criticism—there was just enough there, but not too much. The sweet spot for the critic.”

The Los Angeles Opera will use David Hockney’s 1990s sets for a new production of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot: “Hockney’s scenic design, reminiscent of stark German Expressionist filmmaking with a dash of the backgrounds in Walt Disney’s Fantasia, is a virtuosic testament to the artist’s lifelong exploration of abstract figurative painting and his abiding love of opera.”

Ronald W. Dworkin writes about the “work-home divide” in the latest issue of First Things:

During my first year in medical practice, some of the older doctors criticized me for not wearing a tie to the hospital. “What’s the point?” I shot back. “I just change into scrubs anyhow.” But it was 1989, and the older doctors made me fall into line. Around the same time, the hospital staff discovered that a medical resident had a tattoo on his arm. He was ordered to cover it up with a large bandage. He, too, sheepishly complied.

By the early 2000s, a sea change had occurred. Anesthesiologists like me could wear anything they wanted to the hospital, including shorts and tank tops. On the wards, several doctors and nurses proudly displayed their tattoos. A new deal was making its way through American life.

In the old deal, forged more than a century ago, work life and home life had been rigidly divided. At work, employees conformed to a company’s rules concerning hairstyle, personal dress, and decorum. At home, they could be themselves.

The old deal had supplanted an even earlier deal in which cowboys and pioneers roamed free, unmonitored at both work and play. In 1890, when the Bureau of the Census declared the frontier closed, the zone of personal freedom in the U.S. shrank from the open range (“home on the range”) to the physical building a person called home. Americans moved from farms to cities. They worked in offices or on factory floors. Both sites had rules. The work–home divide began.

The Wall Street Journal reports that YouTube is now the second most popular streaming service in the United States: “Nearly 10% of the time Americans spent in front of TV screens last month was on YouTube’s flagship smart-TV app, Nielsen data show, a sign of continued transformation of the platform.”

A French court has acquitted Roman Polanski of defaming British actress Charlotte Lewis: “Lewis, 56, alleged in 2010 that the Franco-Polish director had sexually abused her at his Paris apartment in 1983 when she was 16 after she had travelled to the French capital for a casting session. She starred in his 1986 film Pirates. She sued for defamation after Polanski called her allegations a ‘heinous lie’ in a 2019 interview with Paris Match magazine.”

Jesse Singal reports on a sad, new crowdsourced spreadsheet that helps readers “boycott or harass authors or harass the fans of authors for holding the incorrect views on Israel.” Seth Mandel explains how dumb the thing is in Commentary:

Pierce Brown is the bestselling author of the dystopian science-fiction series Red Rising. On the blacklist, he is listed as a Zionist and therefore to be avoided. The explanation is that he posted “pro-Israel” content to an Instagram story. You can follow a link to see the evidence for yourself. His crime: “He lamented the loss of life on October 7 while ignoring the history and reality of Israel’s genocidal, apartheid settler state in Palestine.”

So there you have it. Literally, “he lamented the loss of life on October 7” is the entirety of the case against him. You might call him a human being . . . Some of this work takes real sleuthing by this amateur keffiyeh Stasi. Take Stephanie Garber, author of a couple of popular young-adult fiction series. Under the “Zionist: Yes/No” category, Garber is listed as a firm Yes. The explanation was less firm, positing that Garber “allegedly posted pro-palestine messaging previously, however she favorably posted a book by SJM to her instagram story, and then blocked an instagram user after they called her out for it (sic all)” . . . If you’re keeping score: Stephanie Garber should be boycotted because she owns at least one book by Sarah J. Maas, who went to Israel about 20 years ago.

Irina Dumitrescu reviews a new book on medieval minstrels in The London Review of Books: “Despite the scorn directed at minstrels, they were indispensable to medieval society. In The House of Fame, Chaucer imagines Fame living in a castle made of beryl. In the niches he sets every imaginable kind of minstrel, performing stories of woe and of delight – that is, ‘of all that belongs to fame’. Among them are Orpheus playing his harp, the centaur Chiron and a Welsh bard called Glascurion, as well as hosts of lesser harpers. Thousands of other musicians play bagpipes, flutes, clarions and reeds; German pipers demonstrate dance steps; trumpeters provide a ‘bloody’ soundtrack to battle. Chaucer was writing primarily about literary fame, but he recognised that, in a world where literacy was still limited to elites, fame depended on oral performers.”

Ira Wells has an interesting take on Salman Rushdie’s memoir Knife at his new Substack: “Memoir, as a genre, is always torn between revelation and creation, authenticity and artifice. The author promises to reveal the truth of his experience; the narrative insists that that experience take a certain shape and conform to certain formal patterns. Rushdie presents his life immediately prior to the attack as a state of prelapsarian perfection, shimmering with love, friendship, and deeply satisfying work. Were things so perfect? Or has the narrative been massaged into shape so that Rushdie can write, dramatically: ‘Then, cutting that life apart, came the knife.’ Or later: ‘The knife had severed me from my world, cut me brutally away, and placed me in this screaming bed.’”