More Fear-Mongering from the ALA

Also: Milton's apple, the inventor of karaoke, Churchill's networking, Christopher Childers's "Greek and Latin Lyric Verse," and more.

I know, I know. I am starting to sound like a broken record with my complaints against the American Library Association’s attempt to stoke hysteria over parents asking for books celebrating transgenderism to be removed from school bookshelves. But since I started documenting the organization’s exaggerations, I figure I might as well continue until I am suicidally bored with the whole thing, which, I’ll admit, is fast approaching. (Feel free to skip to the links if you don’t want to read about the latest.)

Background: The ALA releases its annual report every April (which is common enough) in which it releases figures on how many challenges to library holdings were made the preceding year. But it runs its “Banned Books Week” every October, which gives it two instances every year to issue a press release lamenting the grave danger to democracy that these challenges pose. Almost every major media outlet—and I do mean almost every single one—follows suit, wondering how long American democracy will last if elementary students can’t continue to check out Gender Queer.

What’s the problem with the ALA’s report on “challenges”? As I argued here last year, the numbers are misleading:

The ALA is pitching the number of challenges (1,269) as an alarming increase—up almost 50% from challenges filed in 2021. It has been tracking these for 20 years, and every year between 300 and 500 challenges are typically filed. So, 1,269 is indeed a big increase. Is it alarming? No.

First, 1,269 challenges across 117,000+ libraries just isn’t that significant. I am guessing that several libraries reported multiple challenges, which means that we are likely talking about less that 1% of libraries across America reporting a request from a patron or parent to remove a book. That would mean 99% of libraries reported no challenges at all.

Second, the ALA is describing these requests as attempts to curtail free speech, but most of them concern material that patrons or parents think is sexually explicit and don’t want their children to read.

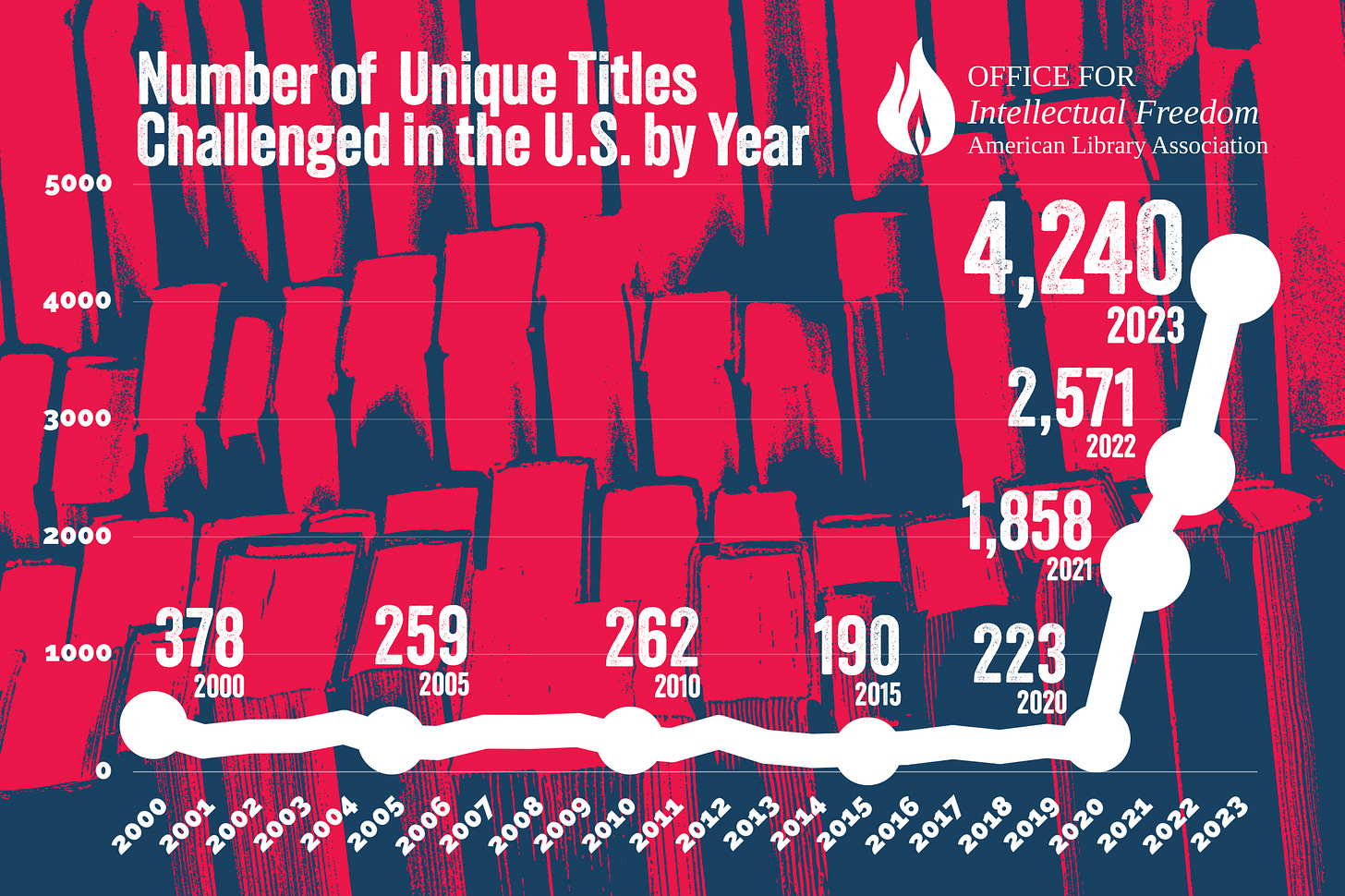

I bring all this back up again because the ALA has released a teaser from its forthcoming annual report last week stating that “Public Libraries Saw 92 Percent Increase In Number of Titles Targeted for Censorship Over The Previous Year.” I have no reason to doubt the number, but what struck me was the graphic:

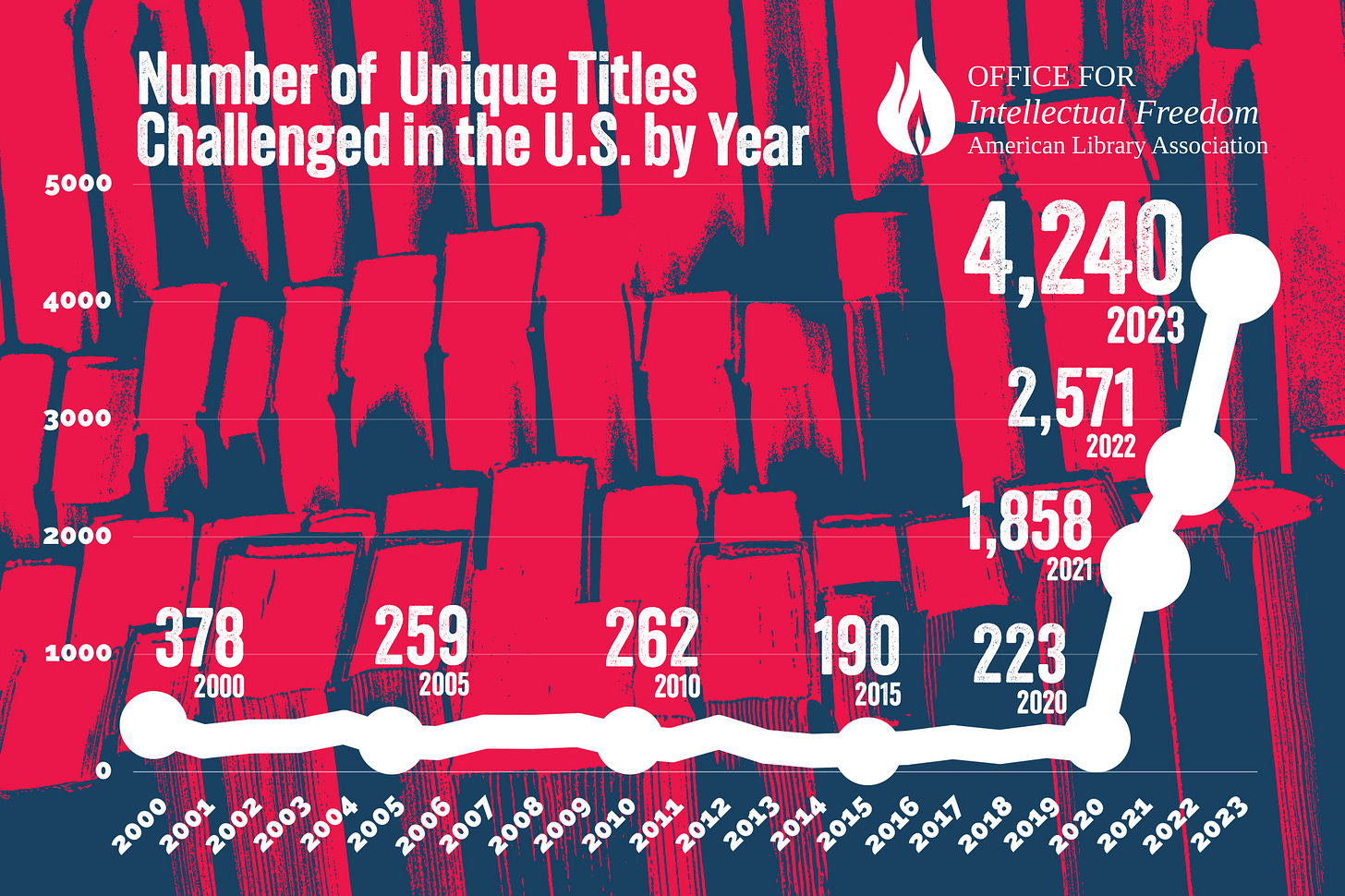

This is different from the graphic released last year, which is now impossible to find on the ALA’s website:

What’s going on here? This year, the ALA is highlighting the total number of books challenged whereas last year they were highlighting the total number of unique challenges. Why? Because the number of single challenges has actually gone down from 1269 in 2022 to 1247 in 2023. (The ALA notes that several challenges contained as many as a hundred books.) That doesn’t help advance the narrative that right-wing parents are a serious threat to democracy, so the ALA is touting the 4,240 figure.

At root, my problem with the ALA is the lack of transparency. They leave out important contextual information in order to raise money by fear-mongering (there is always a link to give to the ALA’s supposed defense of free speech with every press release). How many libraries reported challenges? How many books were actually removed from shelves? Were these at city libraries or school libraries (the ALA doesn’t distinguish between the two)?

It is nearly impossible to find data from previous years on their website (only the latest report is easily available publicly). They use the words “banned” and “censored” equivocally. And they fail to report on how access to ideas may be curtailed in other ways. Earlier this year, James Fishback reported in The Free Press on how school libraries were only making certain books available to students and not others:

I surveyed the library catalogs of 35 of the largest public school districts in eight red states and six blue states, representing over 4,600 individual schools. All of these records are publicly available online. (Here are just three online catalogs I searched: Broward County, FL, Austin, TX, and Oklahoma City, OK.) What I discovered isn’t so much a problem of banned books. It’s that kids are often exposed to only one side of the story.

For example, How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, which argues that the “only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination,” is stocked in 42 percent of the U.S. school districts I surveyed.

Meanwhile, only a single school district—Northside Independent School District (ISD) in San Antonio, Texas—offers students Woke Racism by John McWhorter, a book that challenges the borderline religious “anti-racist” ideas advanced by Kendi.

Felix Ever After, a book by Kacen Callender that claims that girls who hate “being forced into dresses and being given dolls” are transgender, is available in 77 percent of the districts I surveyed. But not a single school out of the nearly 5,000 I searched offers books critical of trans theory. Students won’t find books like Trans by Helen Joyce or Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters by Abigail Shrier, both recent bestsellers that present skeptical takes on the rapid rise of transgender identification among adolescents.

I interviewed the former head of the ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom Committee last year for The Washington Examiner. I quite enjoyed our conversation, and she seemed like a sensible woman who was perhaps unaware of how much things have changed since her tenure ended. The upshot of our conversation, I argued in the piece, is that the ALA could provide some very useful information to the public about these “challenges” but has chosen not to do so:

She told me that she first published Teaching Banned Books in 2001 to encourage a conversation about books that were removed from library shelves. “I think we’re making a mistake when we’re banning books and not having a conversation,” she said.

Teaching Banned Books was updated and reissued in 2019 before many of the more controversial titles, such as Gender Queer and All Boys Aren’t Blue, were published. When I asked her if she would include these titles in a future update, she said she would, but she said that she would not recommend Gender Queer for all students. “Gender Queer was written as an adult book. Do I think it should be in high schools? Absolutely,” she told me. “But I would never recommend it for elementary school. I would never even recommend it for middle school.”

Scales said she was not aware of Gender Queer being recommended to elementary school students, but the book has been made available to both elementary and middle school students in some districts.

While Scales blamed “unreasonable” parents for stoking what she thinks are unfounded concerns about sexually explicit books, she also said that libraries and bookstores have “caused some of our problems” by thinking of fifth graders as young adults. “There is nothing about a fifth grader that is a young adult. I would even argue that middle schoolers are not really young adults. They are entering their adolescence. … Why would we call an 11- or 12-year-old a young adult?” It is “a huge error,” she said.

There is a great deal of confusion about which books are available for which grades in school districts, especially books that contain explicit images and frank descriptions of sexual acts. If the ALA wanted to have an honest conversation about the appropriateness of certain books, a good start might be to report how many of the 151 requests to remove Gender Queer or the 62 requests to remove Flamer originated at elementary or middle school libraries.

The ALA might also consider avoiding inaccurate words such as “ban” or “censor” and use Banned Books Week to focus on books that have actually been banned. It might not create as much publicity as the current iteration of Banned Books Week. But it might be better, you know, for our democracy.

In short, we need more light, less heat, but I won’t expect more light anytime soon—at least not from the ALA.

In other news, Fraser Nelson, the editor of The Spectator, explains what he hopes for in a new owner of the magazine if RedBird’s bid is rejected by the government:

Crucially, neither The Spectator nor the Telegraph need a penny of anyone else’s money. We’re both profitable. We don’t need a sheikh or a sugar daddy. All we need is an owner who will let us invest a bit more of our readers’ money in journalism. So: accept lower but still-respectable profit margins and let us invest the rest. That would give us all the cash we’d need to double our subscriptions yet again.

I believe that anyone who ended up with The Spectator would agree to this fairly modest proposal (albeit with radical effects for us). So resuming the auction process would most likely mean a good owner — and getting the investment in journalism that we need. The risk for us now is that being kept in purgatory, as a long list of people wonder what to do with us.

A. E. Stallings reviews Christopher Childers’s Penguin Book of Greek and Latin Lyric Verse. She loves it: “Clearly this has been a labour of love – Christopher Childers spent over a decade on this tome (‘a sort of personal odyssey, it has detained me for 10 years now’) – or maybe even a love of labour. That anyone would even attempt to sit down and translate a significant chunk of all Greek or Latin lyric poetry, and cram both the Greek and Latin poems into one volume is, let’s face it, a little daft. But it is an inspired and enlightening lunacy. It is rare to be able to say, as a reviewer, here is a work of staggering ambition, exceptional accomplishment, and surprisingly pleasant reading, but here we are.”

Bill Reddinger writes against the renaming of birds: “The American Ornithological Society (AOS) recently announced its plan to rename approximately one hundred bird species that live in North America. Unlike its regular changes to bird names based upon the latest taxonomic data, the recent AOS decision is part of ‘an effort to address past wrongs and engage far more people in the enjoyment, protection, and study of birds.’ But one suspects that the decision has little to do with science or conservation. As such, it suggests an ongoing politicization of American society that’s also bad for science, because scientific knowledge and enjoyment of all things scientific depends upon keeping politics in its proper lane.”

Shigeichi Negishi, the inventor of karaoke, has died. He was 100 years old:

It all began with some friendly teasing on a summer morning in 1967. Shigeichi Negishi, then 43 years old, was singing to himself as he walked into the offices of the electronics company he ran in Tokyo.

“You aren’t a very good singer, Mr. Negishi!” joked one of his engineers. “Give me a break!” shot back Negishi. But in the space of that short, almost forgettable exchange came an epiphany: If only they could hear my voice over a backing track!

And so the idea for the karaoke machine was born, Negishi said in a 2018 interview for my book, Pure Invention: How Japan Made the Modern World. Negishi died from natural causes on Jan. 26, after a fall, according to his daughter, Atsumi Takano. He was 100 years old.

Internationally, the invention of karaoke has widely been credited to Daisuke Inoue, a Japanese musician who released the “8 Juke” in 1971. Later hailed as karaoke’s creator by a Singaporean television show, Inoue went on to be named one of the “Most Influential Asians of the Century” by Time magazine in 1999.

In Japan, however, the existence of singalong machines preceding Inoue’s is no secret. Negishi’s “Sparko Box,” which first came to market in 1967, is recognized as the earliest by the All-Japan Karaoke Industrialist Association, the country’s largest organization of karaoke manufacturers and retailers.

Oops: “A priest on the Spanish island of Tenerife has apologised after accidentally ordering a set of listed, 300-year-old frescoes in his parish church to be painted over as he attempted to ready the building for Holy Week.”

Min Chen reviews the new Frida Kahlo documentary for ArtNet: “While the American patrons rubbed her wrong, her greatest scorn was reserved for the French Surrealists, who were early in championing her work (André Breton famously characterized Kahlo’s art as ‘a ribbon around a bomb’). In 1939, she traveled to Paris for a solo show at the Renou et Colle Gallery, only to find she had nothing in common with the ‘Surrealist cacas.’ She called their works ‘a decadent manifestation of bourgeois art’ and, attempting to distance herself from their ilk, insisted: ‘I never painted my dreams. I painted my reality.’”

How Churchill charmed America: Sean Durns reviews Churchill’s American Network: Winston Churchill and the Forging of the Special Relationship:

Churchill was that rare thing: a genuine genius. There are books on Churchill the painter, Churchill the writer, Churchill the military strategist, Churchill the Zionist, and so on. Yet, Churchill’s success in life—a life filled with remarkable highs and devastating lows—makes it easy to overlook another facet of the man.

Churchill was a consummate networker. And his successes were not just the result of luck or brilliance. Rather, they were the result of hard work and a magnanimous nature, both of which proved essential as Churchill slowly, but surely, built up ties in the New World.

Mark Edmundson writes about Satan’s temptation of Eve in Paradise Lost:

Satan doesn’t tempt Eve only with the narcissistic dream. He offers an expansion of consciousness. He tells her what the fruit has done for him, and leaves her to imagine what it will do for her:

Thenceforth to speculations high or deep

I turned my thoughts and with capacious mind

Considered all things visible in heav’n,

Or Earth, or middle. (IX, 602–5)Satan claims that eating the fruit has expanded his mind: He sees more; he knows more. And so it shall be for Eve. Satan tells her that the fruit—the apple—gives him power to discern “things in their causes” and “to trace the ways of highest agents, deemed however wise.” The last phrase—“deemed however wise”—is a dig at God and the tutelary angel Raphael, who comes to instruct Adam and Eve. There is more in heaven and earth than is dreamt of in their divine philosophy. There is Satanic wisdom to be had.

The American Bible Society will close its $60 million museum in Philadelphia. Emily Belz reports: “ABS had projected that the museum, centrally located on Independence Mall in Philadelphia, would draw 250,000 visitors a year. The revenue from ticket sales for the museum show a much lower number, maybe as low as 5,400 visitors in fiscal year 2022 (the museum’s program revenue was $54,000 and full-priced tickets cost $10).”

Gracy Olmstead considers the lessons of George Eliot’s Mrs. Poyser in Adam Bede: “In each of her novels, Eliot elevates the work of quiet rural communities. But in Adam Bede, Eliot specifically celebrates the work of farm women.”

Michael M. Rosen reviews Dan Stone’s The Holocaust: An Unfinished History: “What more can there possibly be to say about the Holocaust? Plenty, as Dan Stone demonstrates in The Holocaust: An Unfinished History, his sobering and meticulous exploration of aspects of the Shoah that have remained, until now, under-analyzed. And these aspects of the Holocaust are especially salient today, as the Nazis’ carefully orchestrated murderous program has been adopted and adapted by Hamas and other jihadist groups and abetted by their fellow travelers in the West.”

Some library professionals have had it with ALA. They've launched a competing organization, Association of Library Professionals: https://alplibraries.org/. Their homepage says, "Help advance, promote, and defend the values upon which librarianship and modern enlightened civilization stand - institutional neutrality, open inquiry, individual liberty, freedom of thought, freedom of speech, and intellectual freedom." I wish them well. Many new medical and scientific associations have been launched for similar reasons.

Remember seemingly minor things can be particularly insidious. This none sense about changing birds names to promote something or another that we’re all supposed to agree is especially virtuous diminishes historical memory and breeds confusion. If a bird had a name that had a racial slur in it, I can see the point. But that is not what’s going on. It’s more like, we must rename the John Smith Warbler the Rocky Warbler because we did research and found out John Smith , who no one has ever heard of, was in the Confederate Army. So we rename the bird, no one can remember what it’s called anymore and John Smith who no one can remember any way is thoroughly erased and people feel much better now.Talk about moral grandstanding, virtucratic nonesense. You’ve probably heard there was a push to rename The Audubon Society because it was discovered- although it was always known- that Audubon was a slaveholder and in some respects not an example of saintly wokeness.So the one man who probably did more in America to promote interest in bird watching and serious interest in birds besides being a brilliant visual chronicler of them ( his visual work is beautiful), should be erased and maybe the society could be called The Virtuous If Blind Avian Watchers Society .