A Diminished Shakespeare

Also: On moral reading, a fireball over Georgia, an “Africanfuturist heist game,” neurotic Boccaccio, and more.

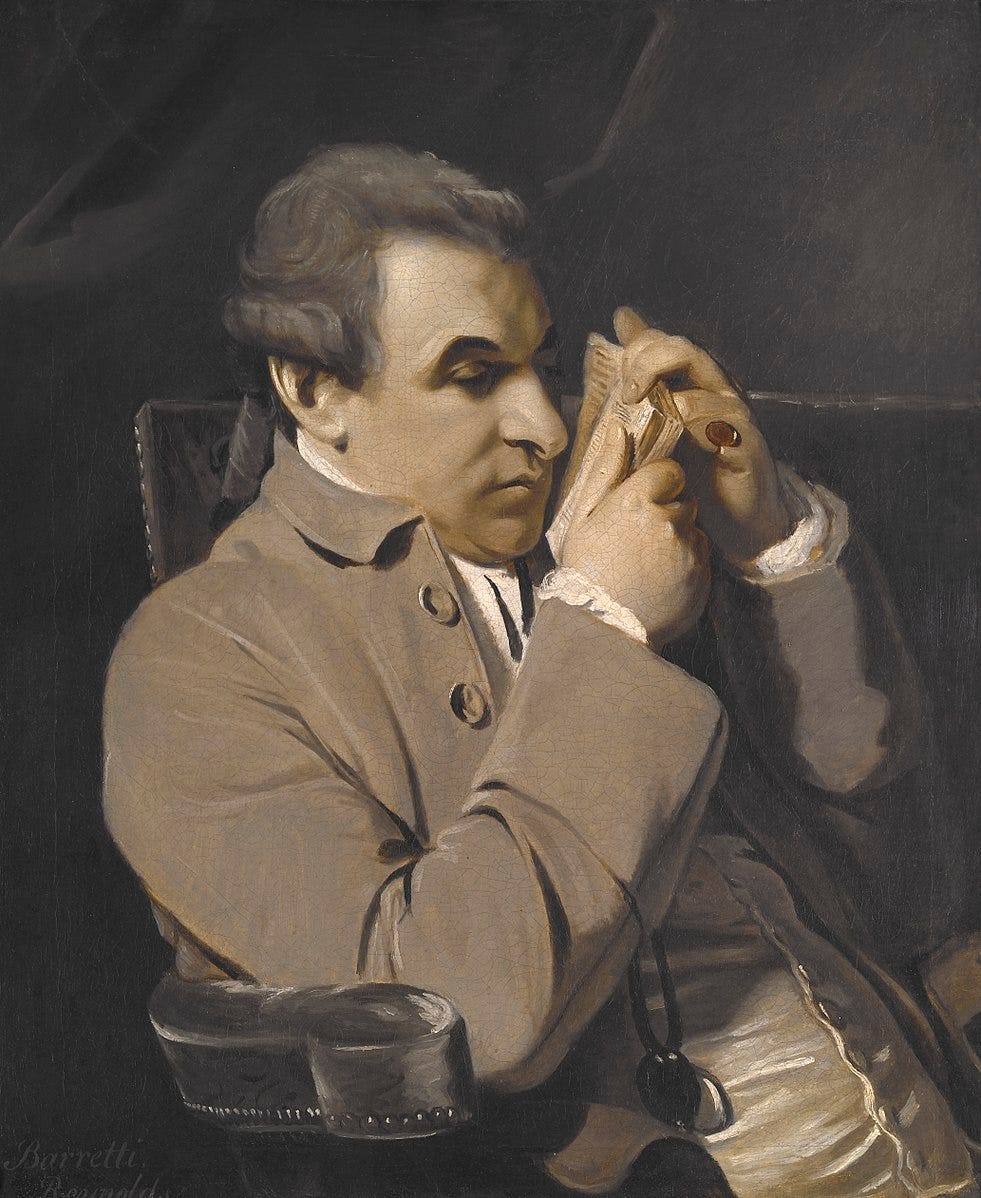

Good morning! Edward Rothstein visits the Folger’s new permanent exhibit of Shakespeare’s Folios:

Last year, the Folger reopened after an $80 million expansion that was really a transformation, adding for the first time a permanent exhibition along with new galleries for temporary shows (now featuring “How to Be a Power Player: Tudor Edition”—a playful survey of “social climbing” as a “competitive sport” in the age of Queen Elizabeth I). Peculiarly, though, it also presents us with a Shakespeare who doesn’t seem worth much attention.

This doesn’t mean there aren’t things worth attending to here. The new permanent exhibition, “Shakespeare: Then and There, Here and Now,” for example, displays the world’s largest collection of First Folios in one gallery. Dimly lighted behind a glass wall are 82 examples of this first collection of Shakespeare’s plays, printed in 1623, seven years after his death. Touch-screens guide us, exploring markings and scars left by four centuries of readers. The “Power Player” exhibition, too, is charming and suggestive.

“But what of Shakespeare’s achievement?” Rothstein asks. “Aye, there’s the rub”:

These explorations of the Folios and Tudor power plays deal with secondary matters—the collection, the era’s sociology—and neither illuminates Shakespeare’s accomplishments. And while the permanent exhibition also includes a working model of a 17th-century printing press (along with an interactive simulation), it reveals nothing about the artistic or dramatic powers of the works printed. Another gallery primarily presents centuries of performance memorabilia.

One ambition of the new Folger, it seems, is to topple Shakespeare from his monumental status. Rather than mount stairs to a grand temple-like portal, visitors now descend on ADA-compliant ramps leading through small gardens to lower-level side-entrances. The entire grand Tudoresque Great Hall is now a Starbuckian (or Falstaffian?) coffee shop.

This is not just a symbolic leveling. The opening gallery of the permanent exhibition—the Folger’s main introduction to Shakespeare’s work—seems written by a middle-school teacher for a middle-school student, both burdened by grudges. “Who was Shakespeare?” reads the opening panel. “A hero? An icon? The name on a book you never wanted to open?” Why would you not want to open it? Is it off-putting because of its aura of elite achievement? Don’t worry, only faint praise is found here. Shakespeare, the panel continues, was “a writer, an actor, and a businessperson.” His reception has made him seem overly grand, or worse. And though his words “outlived him”—and two books on display show him avidly quoted as early as 1600—there is nothing too special about those words: “Sometimes they connected people, sometimes they divided people.” We are urged to “talk back to Shakespeare.”

The exhibit even tries to associate Shakespeare with American slavery: “‘While Shakespeare was writing his plays,’ reads one label, ‘England was colonizing this land that we are currently standing on.’ . . . ‘For far too long,’ we are told, ‘Shakespeare was seen as both the property of white culture and evidence of its supremacy.’”

In other news, Victoria Smith writes about the report “Everyday Cancellation in Publishing,” released last week by SEEN in Publishing. The report shows—unsurprisingly—that the publishing industry is biased in favor of books that present gender theory positively and against books that present it negatively. What’s interesting—but also unsurprising—is that positive gender theory books sell far fewer copies than books that are critical of it. According to the report “books based on gender-identity beliefs” sold 1,328 copies on average. “Gender-critical books,” however, sold 11,554 copies on average.

As Smith notes, the report also “catalogues the way in which many in the publishing industry — authors, publishers, agents, freelances — have seen their careers, health and reputations wrecked by bullies claiming to occupy the moral high ground”:

I knew many of the stories already — people (the vast majority of them women) hung out to dry for such “crimes” as objecting to threats of violence against lesbians, tweeting in support of JK Rowling or writing a picture book to celebrate body acceptance. Even so, seeing them all grouped together made me feel incredibly sad. Such sadness will not be shared by the bullies. As some have already made clear, they’re happy to dismiss the report as “whinging” or even not to read it at all. They’re the goodies, you see. Goodies would never destroy lives unless their victims deserved it.

Even without the report, it’s been clear for some time that certain areas of publishing have more than their share of people who delight in hounding others for the most minor infraction, not caring how much damage they do. The rise of gender identity ideology has been a gift to such people, making anyone who dares to suggest that biological sex is immutable and politically salient — which everyone knows it is — fair game. As Aldous Huxley once wrote, “to be able to destroy with a good conscience, to be able to behave badly and call your bad behavior ‘righteous indignation’—this is the height of psychological luxury, the most delicious of moral treats.” Now all one has to do is find someone tentatively suggesting that single-sex spaces serve a purpose, or that mastectomies for traumatised teens aren’t always a good idea. It doesn’t matter if what they are saying sounds reasonable. The “good” thing to do is break them, then accuse them of weaponising trauma should they complain.

As someone who cares a great deal about books and reading, I’ve found it incredibly alienating and distressing to witness all this. The truth is — and I’m quite embarrassed to admit it now — there was a part of me that always thought being a “book person” made one less, not more, likely to join a raging mob. Once upon a time, I saw the fact that I studied literature — and not just literature in English! — as a mark of my inclusive, open mindset, my interest in other experiences, other feelings, other lives. I’ve since started to fear it’s just those kinds of beliefs that have fuelled the book world bullies. We’re allowed to treat others appallingly because, as book people, we’re naturally thoughtful and empathetic (and anyone who isn’t needs ousting from our inner circle. How convenient to have found a culling criterion that makes “being unkind” a matter of knowing what sex a person is).

Speaking of joining raging mobs, over at Vox, Eric Levitz has a long, muddled piece about how the decline of “deep literacy” might make us more susceptible to demagoguery. He revisits Walter Ong’s controversial argument regarding pre-literate people and abstract thought; then he walks the whole argument back. This is his conclusion: “I do not like what modern media is doing to my brain, nor what illiberal dogmatists are doing to my country. And like Mir and Garfinkle, I’m tempted to draw a line between the two. It feels true to me that technology is coarsening America’s culture and poisoning its politics. And that sentiment may well reflect reality. But if I wish to be objective, it might also reflect the fact I’m a Twitter-obsessed, millennial writer who’s starting to get old.” Let’s be objective.

Lydia Davis writes about why she writes in Harper’s:

I may have thought, as a twenty-year-old, that one wrote to convey a message, as in a serious poem. But I soon stopped thinking I needed to convey a message, or even have a message. I had some messages inside me then, and I still have plenty of messages inside me, but not to convey explicitly or even implicitly in writing, except involuntarily—maybe only in rants or harangues out loud to people. People who would rather I quieted down.

I don’t write to convey a message, and I don’t write stories to achieve any particular purpose. I don’t write stories to persuade a reader of something I believe, though I have many, many beliefs.

I don’t write a story for any particular audience. I don’t think of a reader as I am writing it, though after I’ve finished writing it, I am glad, or touched, if a person enjoys it or is moved by it.

I don’t write a story to move someone, though someone may be moved. It is not that direct. It is more indirect: I encounter something that moves me, I let a story evolve from it, or I guide the material into the form of a story that fits it, that suits the power or beauty of that original material. Then a reader reads the story, and if that reader is of a certain temperament not too unlike mine in one or several respects—for instance, having a similar sense of humor, or any sense of humor at all—he or she may be moved by the story. But moved, I could say, only, in a sense, by my story as intermediary, as conveying what was inherent, for me, as I saw it, or possible, in the original material.

More:

John Clare said, in a poem, that he found his poems “in the fields” and “only wrote them down.” This is not exactly what happens for me—and it probably did not for him—but my experience is that a piece of writing starts with something outside coming in. I write something because it occurs to me to write it—it occurs to me, rather than I go out in search of it. Going out in search of a suitable topic is something I did early on, when I thought, as a twenty-year-old wanting to write “poetry,” that a poem should be serious and have a serious subject, so I should search my mind and experience for a serious subject and then write about it.

This bit reminded me of Walker Percy’s essay “Metaphor as Mistake”:

Some of the pieces of language that persist in my memory are ones that seem stylistically awkward or faulty. One is Ashbery’s (or not Ashbery’s) title “Peter and Mother.” Another is Shakespeare’s “When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang / Upon those boughs. . . ,” which I can hear also as the first notes of the musical scale sung out of order: “mi, or do, or re.” Yet another, which I hear as redundant, I remember from Moby-Dick but is in fact quoted by Melville from the Book of Job: “And I only am escaped alone to tell thee.” (The escape is only temporary.) In the first, British edition of the novel, the epilogue in which Ishmael speaks this sentence was mistakenly omitted. And so it appeared to readers that Ishmael had drowned along with the others—and if so, how could he be telling this story?

A fireball fell from the sky over Georgia: “Like many Southerners I received a jolt today around 12:30 p.m. EDT, when I heard and felt a distinct thudding and shaking at my house in Atlanta.”

Rosita Boland writes about a contemporary circus:

“Pie and mash today,” calls the cook behind the ad-hoc kitchen that has been set up in a car park in Hereford. It’s 4pm, dinner time for the performers of NoFit State, who will be going on stage in the small English cathedral city at 7.30pm . . . I’m sitting at a picnic table with Tom Rack, who is artistic director of NoFit State, and has a long, full beard. He was one of the five people who started the company in 1986.

“We were juggling and roaming around in the summers, and then in the winter we came together to make shows for schools, so we could avoid getting proper jobs,” he says. “We fell in with a chap with a big top, back in the day of local-authority festivals and events, and he realised if he hired the five of us we’d drive the lorry, and do the workshops, and do the shows, and work the bar, and that was our introduction to the big top.”

A new “Africanfuturist heist game” has players steal artifacts from Western museums to send them back to Africa.

Alexander Lee reviews the new Boccaccio biography for The Literary Review:

In early June 1363, Giovanni Boccaccio received a letter that stung him deeply. Just a few days shy of his fiftieth birthday, he was then at the height of his creative powers. He had already penned at least a dozen major works, including the Decameron, any one of which would have assured him a place alongside Dante and Petrarch in the firmament of Italian literature. Although recent political upheavals had forced him to leave his native Florence, he was still writing feverishly. Yet to his friend Francesco Nelli, the author of the letter, he remained a ‘man of glass’. He was painfully fragile: fickle, oversensitive and quick to anger – in short, a neurotic pain.

Boccaccio denied it, of course. He wrote a long reply, rebutting Nelli’s charges in exhaustive, some might say pedantic, detail. But as Marco Santagata’s biography shows, Nelli was nearer the mark than Boccaccio was prepared to admit. And the ‘proof’ is right there, staring us in the face. Like Dante and Petrarch, Boccaccio was a relentlessly autobiographical author. His tales, even when set in another time and place, were embroidered with vignettes of his social world, and he could seldom resist the temptation to insert himself into the plot – either overtly, as the narrator, or discreetly, in the guise of characters. By teasing out the details contained in these literary self-portraits, Santagata argues, it is possible to build up a picture not just of his life, but of his personality too.

And what a striking picture it is. Although Boccaccio was never exiled from Florence, as Dante was, he spent most of his life outside the city and wrote many of his most important works elsewhere. The son of a Florentine merchant and an unknown woman, he was taken to Naples while still in his teens and grew up on the fringes of the Angevin court. He was destined for banking but, realising he hated it, persuaded his father to let him abandon his apprenticeship and study canon law, presumably in preparation for a career in the Church. Just months before completing his degree, however, he suddenly threw in the towel. Flitting around Italy in pursuit of his literary passions, he struggled to shake off a feeling of insecurity and doubt. He craved the approval of the rich and the powerful, yet never quite managed to achieve it. His awkwardness with Latin, then still the lingua franca of intellectual life, was a perennial source of anxiety. His lack of discretion didn’t help either. As Santagata notes, he was prone to flashes of temper and fits of ‘almost infantile egocentrism’. Other than with Petrarch, whom he idolised, his friendships were rarely free of tension. He admired Niccolò Acciaiuoli, a fellow Florentine who rose to become grand seneschal of the Kingdom of Naples, but envied and resented his success. Even his family irked him at times.

Bryan Karetnyk reviews a new edition of the 1937 Short History of the USSR: “Picture a rather bizarre scene. It is the summer of 1937, and Stalin’s Great Terror is at its zenith. Yet in between signing list after list of names marked for execution, the Father of Nations removes to his dacha at Kuntsevo, west of Moscow, where, undisturbed, he sits down to edit a set of galleys for a new history textbook intended for schoolchildren across the Soviet Union. Under the circumstances, this excursion from mass murder may seem unexpected, extraordinary even. But in a land where power has forever rested on narrative, history has always been a vital instrument of governance and control.”

The Folger's attempted reduction of Shakespeare breaks my heart. "Attempted" because hope springs eternal. May stronger souls prevail.

Oh man, I remember the Twitter storm when that agent got fired for saying she agreed with J.K. Rowling.